Eden's Outcasts (62 page)

Authors: John Matteson

It seemed to Bronson that his old friend was pleased with

Sonnets and Canzonets

. Although he sometimes failed to recognize old friends, Emerson was still responsive to poetry, and he pleased Bronson by reading several of the sonnets aloud with emphasis and evident delight.

21

Emerson himself had written nothing of consequence since his eulogy for Thoreau, some twenty springs before. At that time, Bronson had yet to taste a single publishing success, and Louisa had been grubbing along, a story here and a poem there. Now both enjoyed reputations fit to be considered alongside Emerson's own. Emerson had always maintained that each life had its unique value. The difference in circumstance between one destiny and another was, in his view, merely costume. “Heaven,” he had written, “is large, and affords space for all modes of love and fortitude.”

22

Before his own powers fell into deep decline, Emerson had had the satisfaction of knowing that Bronson and Louisa had found their places too.

One day in mid-April, Emerson forgot his overcoat and caught a chill. On the twenty-first, he closed up his study and walked upstairs to bed. He did not come down the next day. Five days later, on a cloudless Wednesday morning, Bronson came to Emerson's door. Ellen conducted him upstairs to the sickroom, where he went to the bedside and took the hand of his friend. Emerson ventured to ask, “You are quite well?”

23

Bronson replied that he was but that it was strange to find Emerson in bed. Emerson tried to say more, but his words were broken and indistinct. After an interval, Bronson thought he should go. Before he could leave, however, the dying man indicated that he had something more to say. Bronson told Louisa what happened next, and she wrote it in her journal:

E. held [my father's] hand, looking up at the tall, rosy old man, & saying with that smile of love that has been father's sunshine for so many years, “

You

are very well. Keep so, keep so.” After Father left he called him back & grasped his hand again as if he knew it was for the last time, & the kind eyes said, “Good by [

sic

], my friend.”

24

Bronson felt shaken as he made his way home. When Lulu met him at the door, overflowing with childish babble and joy, he felt a wave of gratitude.

25

The next day, April 27, 1882, Emerson passed away. Louisa, who had once complained of having been entirely isolated in her strivings for literary glory, now freely admitted that she had not been alone. Not only had Emerson been the best friend that her father had ever had; he was also “the man who has helped me most by his life, his books, his society. I can never tell all he has been to me.”

26

In a piece for

The Youth's Companion

, with an openness that she had never expressed in print when Emerson was alive, Louisa now recollected how, at fifteen, she had ventured into his library and bravely asked for recommendations. Her father's friend had patiently led her around the book-lined room, introducing her to Shakespeare, Dante, and Goethe. When she expressed interest in books well beyond her comprehension, he had smiled indulgently and advised her to wait. For many of these books, Louisa confessed, she was still waiting, “because in his own I have found the truest delight, the best inspiration of my life.”

27

On Sunday the thirtieth of April, Emerson was laid to rest. Louisa fashioned a golden lyre out of jonquils, which she placed in the church for the funeral. The private ceremony at Emerson's house was followed by an impressive public service, attended by a large crowd. Bronson read the sonnet in which he had proclaimed his affection for the deceased. Then he and Louisa again made the now familiar journey to the remote corner of Sleepy Hollow. The hilltop under the pines was filling up with heroes, family members, and friends, and their world was becoming correspondingly emptied.

Yet paradoxically, with each new departure, Bronson's stature seemed to increase. He was essentially the last man of the generation that had made Concord a center of the American intellect. He was a living link between minds and moments now past and new listeners eager to ask “What was it like?” By the same token, he had outlasted his critics. He had won followers among those who were too young to remember him either as a troublesome outcast or a ridiculed pariah, but knew him only as a kindly sage. Strangely, although he had devoted so much of his life to cultivating his inward existence, he had arguably succeeded much more notably as a friend than as a philosopher.

That summer, Bronson opened the Concord School of Philosophy for its fourth year. By Louisa's count, he gave fifty lectures during the session, an astonishing total for a man of his years.

28

Louisa arranged flowers and oak branches to adorn the school but made herself scarce when the reporters came. A highlight of the program was Emerson Day on July 22, which Louisa called “a regular scrabble.”

29

Bronson's school was now firmly established, not only having won credibility among metaphysicians, but also having gained respect from the many Concord townspeople who respected dollars more than dogmas. As Louisa wrote in her journal, “The School is pronounced a success because it brings money to the town. Even philosophers can't do without food, beds, & washing, so all rejoice & the new craze flourishes.”

30

Bronson would surely have tried to meet everyone who came if Anna had not cooled his ardor by showing him a list of some four hundred callers. Bronson Alcott, aged eighty-two, had become a profitable tourist attraction.

The acclaim had its drawbacks. Bronson, who had long hoped for public attention, was not always at ease now that it had finally come. He was besieged by reporters, who, it seemed to him, were determined to miss the true flavor of his remarks. Whenever a newspaperman came to report on one of his discourses at the school, Bronson felt himself being exposed to “misconception and frequent mortification.” Although his conversational style might have been expected to find favor with lay listeners, Bronson found it hard to win over the gentlemen of the press, who seemed to come prepared for something more elaborate and imposing. It seemed that his “finest and subtle transitions” never made their way into the reporters' notebooks. The full sense of his observations was invariably lost, and the resulting transcriptions were “hardly more than a medley of incoherent thoughts, a jumble of sentences.” The good news, of course, was that people were no longer calling him crazy, and the misunderstandings he now had to endure, while frustrating, had no undertones of malice. Also, he was now wise enough to know that misinformed publicity was publicity all the same. “Let it pass,” he told himself.

31

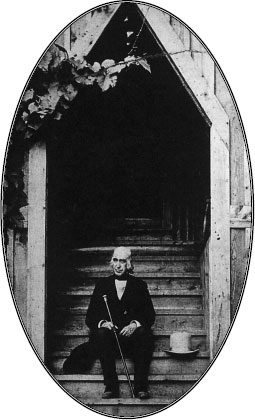

When he was not busy giving conversations and chatting with the school's attendees, Bronson had time to take a step back and look at the loveliness he had helped to create. The rustic chapel and the foliage entwined about its door were beautiful to his eyes. Someone was thoughtful enough to photograph Bronson sitting on those steps. He holds a cane, looking as if he had just arrived after walking a long distance, and his smile is one of a satisfaction beyond price. The distance he had come to sit on these steps was indeed incredible. One rarely sees an image of a man more precisely in his proper place.

A delight of Bronson's old age was his Concord School of Philosophy. Here he sits proudly at the entrance to the Hillside Chapel.

(Courtesy of the Louisa May Alcott Memorial Association)

On September 30, 1882, Bronson and his one surviving sister made a pilgrimage to the old family farm at Spindle Hill. The two passed the day walking down the roads and wood-paths that had once defined their world. The fields no longer yielded any harvest. The fences had vanished, as had the simple farmhouse where Bronson had been born. Sweet fern now grew in wild abundance where he had once labored to sow the seeds of his father's crops. The trees in the orchard had become leggy and unproductive and then had mostly died away. Bronson struggled to call up recollections of the old neighbors, their descendants now scattered. Most of the houses were abandoned. At the others, unknown faces appeared in answer to a hopeful knock. As Bronson wrote, “all [was] gone to ruin.”

32

Still, Bronson himself felt like anything but a ruin. His appetite for life was as insatiable as ever. He had lately written a pair of sonnets on immortality. As the autumn rains fell outside his window, he wrote not of his nostalgia but of his “thoughts of the future.” Although he admitted some curiosity about “the geography and way of life” he would encounter after death, he still thought Thoreau had spoken wisely when he advised people to live in “one world at a time.”

33

Nearing eighty-three, he was eager to know what services he had yet to perform on this side of the grave. The great charms of this life, he still believed, were to have work and to enjoy doing it.

In October, in Boston, Louisa finally felt well enough to begin work on

Jo's Boys

, the last of the

Little Women

trilogy. On the twenty-second, John Brown's widow paid a visit to Bronson, whose kindness to her family she had never forgotten. She spoke in monosyllables and was not interested in answering Bronson's questions about her. Bronson may have read her the sonnet he had written on her late husband for

Sonnets and Canzonets

, which eulogized Brown as a prophet of God and the messiah of the slaves. That evening, Bronson took tea with William Torrey Harris at Orchard House, where the two men and a caller named Ames disputed long into the night regarding the significance of the fall of Adam. Alcott tried to explain his theory of the first disobedience and of man's rehabilitation, but Harris and his friend were unconvinced. Bronson recorded in his journal his failure to persuade them. He had written his last sentence.

34

On the twenty-fourth, barely started on her new manuscript, Louisa received a telegram. Her father had suffered a massive paralytic stroke.

35

She rushed to Concord, but there was nothing she could do. Although Bronson appeared to recognize Louisa, he could not speak, nor could he move his right side. Louisa found the transformation from a vigorous man to a helpless invalid almost unbearable to look on. It seemed to her that, all at once, her father was tired of living, though, as she put it, “his active mind beats against the prison bars.”

36

The doctors offered little hope, and Louisa and Anna spent anxious days both fearing and, for Bronson's sake, half hoping that the end would come soon.

Bronson was a strong man, however, and the stroke could not wholly destroy what it had tragically disabled. If his face seemed vacant to Louisa now, it also seemed oddly contented as he sat in his invalid's chair and gazed out on the world. Although he remained speechless for several weeks, it was evident that he was trying hard to recover. He could not read, but he liked holding books and looking over their pages. Fifty years ago, he had taught children how to write. Now he faced the task of teaching the same lessons to his left hand, the only one that he could now control. By November 4, he was able to make letters on a sheet of paper. Occasionally a word was produced, although the letters most often came out in a random order. Friends sent good wishes, but Louisa thought he was not yet able to comprehend them.

37

As November passed, he slept most of the time. Even as his doctor warned that death was imminent, some of Bronson's faculties gradually started to return. At the beginning of the month, he was able to consume only milk and wine jelly. By the eighteenth, he was able to take spoon food and to speak in a halting, broken voice, sometimes putting words together in a way only he understood. His first intelligible word was “up,” an utterance that Louisa thought “very characteristic of this beautiful, aspiring soul almost on the wing for Heaven.”

38

In general, however, Louisa was troubled all the more by what she regarded as “this pathetic fumbling after the lost intelligence & vigor.”

39

Bronson, for his part, seemed focused on positive thinking. When his words could be deciphered, they played down the seriousness of his condition and reaffirmed the strength he felt in God. Even when he was asleep, Louisa overheard him say, “I am taking a predicament,” “True Godliness and the Ideal,” and “The Devil is never real, only Truth.”

40

While Louisa prayed for a speedy end, it seemed that Bronson's heart was set on a speedy recovery.

On November 29, the two were together for their birthday. Bronson enjoyed the fruit and flowers he received from well-wishers, but he was quite positive that he was turning twenty-three instead of eighty-three. Louisa, he insisted, was a girl of fifteen.

41

At Christmastime, Sanborn and Harris came to call. They were to become frequent visitors at Bronson's bedside, although Louisa continually feared that their high spirits would excite her father more than was prudent. From time to time, she even turned the two friends away, believing that her father required rest more than stimulation. On this occasion, though, the influence seemed all to the good. As his two disciples rallied him with pleasantries about the School of Philosophy, Bronson sat up among his pillows and laughed at their jokes. Louisa had decorated the window with a green wreath. Noticing it, Bronson touched it over and over again, saying, “Christmas. I remember.”

42