Edgar Allan Poe and the London Monster (22 page)

Read Edgar Allan Poe and the London Monster Online

Authors: Karen Lee Street

“Promise me you will be there.” Mrs. Fontaine touched my arm gently.

“Madame, I could not refuse you.”

Her smile was captivating. “I will give you the address.” As she reached into her beaded purse, her fine paisley shawl slipped back from her shoulder, and I glimpsed an extraordinary thing. Pinned to her dress was an fantastical brooch painted in the finest detail: a life-size vivid depiction of a

human eye. That eyeâbrown, lustrous and piercingâglared alarmingly, turning me immobile with dread.

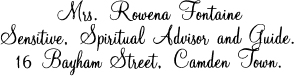

Mrs. Fontaine readjusted her shawl, breaking the eye's terrible gaze. She handed me a visiting card. “The address is here. We begin at eight o'clock. Goodnight, Mr. Poe.” She inclined her head to Dupin, who suddenly was at my side. “Goodnight, Chevalier Dupin.” She hurried away, her silk taffeta dress rustling like leaves before a storm.

I looked down at the card in my hand. In fine gilded script it announced:

“Of course you must not go,” Dupin said.

“Indeed? And why is that?”

“Mrs. Fontaine is most assuredly a fraud.”

Dupin's words irritated me, and I felt the need to defend the lady. “There are mysteries in this world that the most renowned Analyst cannot fathom. She knew your nameâI did not introduce you.”

Dupin puffed air through his lips. “That is not a difficult trick. I am not the ghost you imagine me to be. My presence in London has been observed, of that I am certain. Your presumptions regarding the limitation of Analysts may be correct, but I am not wrong regarding the limitations of your medium. And so I must try to dissuade you from attending her theatrical.”

“I am afraid you cannot.”

“Not if I tell you that your Mrs. Fontaine must be in league against you with Mr. Mackie and others of dubious character?”

“Your accusations sound rather desperate. Mrs. Fontaine

showed no acquaintance with Mr. Mackie and vice versaâand I cannot think what âothers' you mean.”

“The man I pursued from the Institute.”

“Did you apprehend him?” I asked.

“No.”

“Then I am confused, Dupin. Why do you suppose he was with Mrs. Fontaine? They did not sit together or leave together. What gentleman would allow a lady to make her own way home?”

“I doubt very much that he is a gentleman, and while they did not leave together, I am quite certain they arrived together. I observed them enter the theater simultaneously, but after a brief glance into each other's eyes, they chose seats in different parts of the audience. There was an

understanding

.”

“What kind of an understanding?”

“That I do not as yet know.”

“Well then, surely we should attempt to ascertain more by attending the séance,” I said, pleased with my own show of ratiocination. “If Mrs. Fontaine is in collusion with the darkhaired man as you claim, then we have the opportunity to discover their motives. Or perhaps Mrs. Fontaine's motives are pure, and I will indeed receive a message from my grandmother. One thing is certain, Dupin. The lady has information I need, be it gleaned from the dead or the living, and I intend to find out what it is.”

“I notice you say that âwe' should attend the séance,” said Dupin coldly.

“I would very much welcome your company,” I said. “And your protection.”

Dupin was silent for a moment, most dissatisfied with my pronouncement and not entirely persuaded by my flattery. “Very well,” he said at last. “You are quite right. We must on occasion risk all we hold dear to discover the truth. Let us

attend tomorrow's séance, but let us also remain vigilant. Now shall we return to Brown's or would you like to speak further with your audience?”

A few clusters of people remained in the room chatting, but they seemed to have little interest in speaking with me. “I am more than ready to leave.”

“Then let us.” Dupin gestured toward the door, inviting me to precede him.

It did not take us long to find a coach, and we settled in for the journey back to Brown's Genteel Inn. Dupin pulled his meerschaum from his pocket and tapped in tobacco. I did the same, although I would have preferred more of Mr. Godwin's Scotch courage.

“I would say the occasion was a great success,” Dupin offered.

“Unfortunately, I would disagree with your assessment.” Dupin prepared to speak but I raised my hand to halt any words of solace. “Pity does not comfort and the overly generous critic is not a friend.”

Dupin raised his brows slightly. “You are disappointed that Mr. Dickens did not attend.”

“Or perhaps did not desire to.”

“That, I am quite certain, is not the case, but we must wonder at this stage if Mr. Dickens was truly the one to organize the reading.”

“But Mr. Godwin met with Mr. Dickens, who professed to admire my work.”

“Mr. Godwin did of course meet someone who

claimed

to be Mr. Dickens when he organized the reading, but that person may have been an impostor. We must not forget that Mr. Godwin is ill-acquainted with literary figures.”

I immediately remembered how our host had presumed Dupin to be me, and Dupin smiled, guessing my thoughts.

“The impostor may have been Mr. Mackie or the dark-haired man I pursued. We have no proof, in fact, that Mr. Dickens has been in correspondence with you at all,” Dupin said with an irritating note of triumph in his voice.

“Nothing but a hoax,” I muttered. Dupin's suppositions left me feeling all the more dissatisfied with the evening. Not only was my performance of questionable merit, but my hopes of meeting Mr. Dickens might have beenâand might still beâutterly in vain.

Dupin offered no words of comfort but merely lit his meerschaum and exhaled smoke out of the coach window.

“And there is an apparent coincidence we must consider,” he eventually said.

“Pray tell?”

“The date selected for your reading.”

“The eighth of July? Mr. Dickensâor his impostorâsuggested it.”

“Exactly,” Dupin said. “It is a date of significance to our investigation.” I had no idea what Dupin was referring to and he reacted with impatience at my bafflement. “The eighth of July 1790âthe date of quite another performance: Rhynwick Williams's first trial.”

It was as if Dupin had delivered a blow to my chest. I felt completely hollow and could not speak. Dupin did not bother to. We were soon back at Brown's and my mood was as dark as the night sky.

“Do not torture yourself,” Dupin finally said when we entered the foyer. “We will discover your aggressor and vanquish him. Have no doubt.” He gave me a slight bow. “Goodnight, Poe. I wish you a night full of sleep and free of dreams.” And he was gone.

I looked to the desk clerk for any messages, but he simply shook his head. Exhausted, I climbed the stairs to my room,

and when I entered, discovered that the Argand lamp was lit. Sitting in a pool of amber light was a bottle of cognac. I stared at the delectable apparition before me, waiting for some spirit or genie to emerge from it, but it simply shimmered in the supernatural glow of the lamp.

I approached the bottle and there tucked underneath it was a folded piece of paper. My quivering fingers reached for the note, my mind racing.

1 Devonshire Terrace, London

8 July 1840

Dear Mr. Poe,

Heartfelt apologies for being unable to attend your reading tonight, but I am left completely indisposed by the bad wine served at my publisher's house last night. I would appreciate the irony of the situation much more if my health were less compromised. I am certain your reading will be a great success and hope you will forgive me for missing your London debut.

Your Humble Servant,

Charles Dickens

How I wished to believe that the note was truly from the great man himself! But Dupin had poisoned my mind with suspicion, and I could not help but wonder if it was a forgery. I sat for a time, staring at the glowing bottle as if hypnotized, the strangeness of the mystery in which I found myself filling me with its darkness, and when I tried to stifle those unpleasant thoughts, my failure as a performer weighed heavily upon me.

Forgery or not

,

it will do no harm to sample the gift

, said a small voice within me.

I poured a generous measure of cognac into the glass that was stationed by the bottle and cupped it in my hands to warm the contents. The cognac's scent drifted upâit was like a summer's day back home, full of clover with a hint of honey. I was transported to the banks of the Schuylkill, back to the gentle companionship of Sissy and Muddy. Bees glided through a river of pink and white clover blossom, the sun catching flashes of pollen on their busy legs. Soon the glass was empty and I took another and yet another, enchanted with the elixir's ability to bring my memories to life and to blanket my disappointmentsâindeed to alter the past!

I was back in the theater, no need for a lectern or papers as I moved freely across the stage, reciting my lines without faltering, face and voice conveying each character, my stride, my arms, my hands articulating every sentiment. My audience was gripped, intoxicated with my words, each face written with the emotion of my choosing. First tensionâa tightening of the lips and eyesâthen hands twisting anxiously and a stiffening of the upper body as fear trickled down the spine. A false calm set the eyes blinking with relief and the shoulders relaxed, but then, in a cunning final twist, the eyes widened and the mouth gasped in absolute horror. The audience was an orchestra, and I was their conductor. They were compelled to respond!

A sharp sound shattered this illusory world, and I found myself in the middle of the room, my now empty glass clutched in my fingertips. I spun to look around me, and my heart galloped at the sight of a man staring back at me.

“Who are you?” I staggered to confront him, and as his face came closer, I realized with shame that he was but a reflection of meâmy own William Wilson. I sank to the floor, my humiliation transforming to laughter at the absurdity of my situation. I noticed then that a heavy tome was lying on the carpet with papers scattered around it. After scrabbling about,

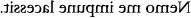

collecting the papers into a tidy heap, I was left with a terrible thirst and so made my way back to the cognac bottle. Had the stuff evaporated? I poured a generous dollop and returned to the heap of papers, which I lifted to my desk. But something was not right. Disarrayâall was in disarray. I eventually fathomed that the mahogany box I had been using as a makeshift bookend had been moved. I grabbed for the box and pulled at the lidâsecurely lockedâthen collapsed into the chair and savored some cognac with relief. It was then that I saw the folded piece of paper lying on my writing desk. Very peculiar, very peculiar. My throat dried up with fear; I quenched its aridness with cognac and opened the note. Inside was a jumble of letters:

The writing was very neat and familiar. Could it be? I opened my writing desk and removed the lament. I am not a master of autography like Dupin, but it was more than plain that the person who had written the note had also transcribed the lament.

I looked at the paper again and my feverish brain immediately knew how to decipher the jumbled letters. I staggered to the mirror, held the paper up to it and stared at the reflection. There in the glass was my double, in the very agonies of dissolution, holding up a letter that warned:

Nemo me impune lacessit

. The man with my countenance leaned toward me and whispered in my own voice, “No one insults me with impunity.” There was a crash and all light was extinguished.

93 Jermyn Street, London

5 May 1790

Dearest Accomplice,

Three ladies in three days,

Felt the sharp edge of my blade,

Three ladies in three days,

Were terrorised and made afraid,

Three ladies in three days,

The Monster's reputation will never fade!

With deepest affection from,

the Extraordinary Fellow Himself

93 Jermyn Street, London

16 May 1790