Edie (28 page)

Authors: Jean Stein

GERARD MALANGA

Andy would always lie to people in his interviews. He’d always say he was out of McKeesport or Pittsburgh. It was never the same place in different interviews. He’d also lie about his age. This outraged me actually, because I was a fiend for accuracy. Then I realized it can be a very Duchamp type of situation, to create a myth for oneself, an identity.

ISABEL EBERSTADT

Andy told me that he was sick a lot as a child, that he had three nervous breakdowns before he was eleven. “Always in the summer, I don’t know why,” he said to me. He couldn’t remember much about his early schooling. His mother was protective and wouldn’t let him go out much so he used to lie in bed and play with dolls and dream about having a glass of fresh orange juice in the morning and a bathroom of his own. He started drawing, copying the Maybelline ads of Hedy Lamarr.

CHOCK WEIN

He said he had St. Vitus dance as a child and he lost his hair and couldn’t hold his hand steady; he couldn’t write on the blackboard. The other kids would beat him up, which made him terrified of socializing. He retreated into movie magazines—the glossy photos and images rather than the printed word.

PHILIP PEARLSTEIN

When I first met Andy at Carnegie Tech in 1945 he was naive and unworldly like any kid in Pittsburgh would be. I had gone to college there before I went into the Army, and then came back for the three years. We were both sophomores. He was younger than the ordinary sophomore because his mother had registered him in grammar school early. And then most of the people in the class were veterans, so we were all older than Andy and the girls.

He was very quiet. He was doing these eccentric drawings that the faculty didn’t like—Aubrey Beardsley-type things . . . only wavy lines. It wasn’t that he refused to conform; like any young kid, he was just doing what he did naturally. The faculty, I gather, had wanted to throw him out of school at the end of his freshman year. I think he had trouble with his academic courses. It was mostly a communication problem; he didn’t quite understand what they were saying.

We were in a class together—it was kind of a therapy course where you’d talk about how an artist finds images that wI’ll be meaningful in terms of his life, and how to project them. That’s when all of us really began drawing a lot, particularly Andy. His style began developing—a kind of unique style in response to these problems. In our senior year, Andy and I collaborated on a children’s book project. I wrote the story—it was going to be called “Leroy”—about the worm inside a Mexican jumping bean. Andy made the illustrations, but in the finished artwork he misspelled it and it came out “Leory,” which was much nicer.

I got to know Andy pretty well. He would come over to my house to work because he didn’t have room at home. There were some nieces and nephews who wouldn’t let him work in peace, and they’d destroy his work. His brothers made fun of him—they thought he was strange because he was doing art.

Andy Warhol, age twelve

When we finished school Andy’s first idea was to be an art teacher in the public school system. Then he got a job doing displays at Joseph Home Department Stores and he began studying fashion magazines in depth—they gave him a sense of style and other career possibilities. So I talked him into going to New York that summer of 1949. He said he wouldn’t go unless I went, he just didn’t feel secure enough. We each had a couple of hundred dollars.

One of our teachers at Carnegie Tech was Balcomb Greene, a big-name artist from New York. He lined up an apartment for us on St. Mark’s Place—right off Avenue A. It was terribly hot. A six-floor walkup. Two or three rooms. Cold water. Bathtub in the kitchen. Andy had a terrific portfolio of drawings he had assembled, and by the end of the first week he had an assignment from

Charm

magazine for a full-page drawing of shoes. He got these jobs constantly.

All the time I lived with Andy, he was very quiet and went to church a couple of mornings a week. Occasionally, we went out to the movies, and those were the only times we’d have aesthetic discussions, if you could call them that. I remember Andy saying once that a movie we’d seen on Forty-second Street was terrible. I said that I didn’t think it was possible for any movie to be uninteresting, no matter how dumb; there was always something going on that was interesting. He didn’t answer, but perhaps that made an impression.

ANDREAS BROWN

Andy was very naive, very innocent, but very determined. He was extremely ingenious about ingratiating himself. He would go to the advertising agencies with a little bouquet and he would give each receptionist or secretary just a single flower in that wonderful mute way. Everybody else dressed in Brooks Brothers suits and carried beautiful leather portfolios, but Andy always came in ragged clothes, and he often carried his work in a brown paper bag. Everybody felt sorry for him.

GEORGE KLAUBER

I used to think of Andy as a hanger-on. There were times when he had nothing to do, and I used to take him places on weekends. He should never go to the beach because he had a skin problem. He would get burned fiercely. One of the comic images I have of Andy is remembering him in a white shirt, no tie, chino

trousers, and sitting on the beach with a black umbrella over his head. That was East Hampton. We used to stay in a rooming house on the other side of the tracks.

HENRY GELDZAHLER

One of the strange commissions Andy had during the Fifties was doing the weather on television—his hand on the screen drawing clouds, or the sun, or sparrows in the rain. I always thought that one of the reasons Andy was so pale was because he had to get up so early, at five o’clock in the morning, to be at the TV station to get make-up put on his hand.

PATRICK O’HIGGINS

During his shoe period Andy’s new apartment in the Thirties and Lexington was one floor up. Two rooms. Very simple indeed. No furniture. Like a room out of the set of

On the Waterfront.

In the kitchen I think there was a picture of Christ pointing to his Sacred Heart, and that’s about all. Piles of magazines. Movie magazines. I remember thinking, “How strange, why would he keep such things?”

As soon as he made a few dollars, he brought his mother to New York. She was a Czech lady, spoke English brokenly, so she spoke Czech to Andy, who answered in English. She looked a little like a Buddha, a solid, square figure of a woman with her hair pulled back in a gray, almost white bun. She looked like Madame Helena Rubinstein without all the trappings.

There was only one bedroom. I know for a fact that Andy shared it with his mother. He told me so.

PHILIP PEARLSTEIN

Andy wanted to have a show at the Tanager Cooperative Gallery on Tenth Street—at the height of its glory then. I was a member. He submitted a group of boys kissing boys which the other members of the Gallery hated and refused to show. He felt hurt and he didn’t understand. I told him I thought the subject matter was treated too . . . too aggressively, too importantly, that it should be sort of matter-of-fact and self-explanatory. That was probably the last time we were in touch. The next thing I knew came the Campbell’s Soup can. Andy and I just lost contact altogether.

EMILE DE ANTONIO

Andy was doing very well. He started to collect things. He moved out of his apartment and bought this decent-sized

townhouse on Lexington and Eighty-ninth Street, next to the National Fertility Institute. He installed his mother. Her presence wasn’t real; it was ectoplasmic. When she did float through, Andy would sort of guide her away. Andy told me that she cleaned the house compulsively: got up at five o’clock in the morning and cleaned everything and then started drinking. She went to bed very early.

On empty nights I’d walk up Park Avenue and over to Andy’s. He poured Scotch whiskey, but he never drank it. He looked like a super-intelligent white rabbit. Paintings appeared.

Dick Tracy. Before and After.

One night two paintings were put up, one against the other. One was a Coke bottle, nothing else; the other was limned with the brushy strokes of an East Tenth Street failure, second-generation Abstract Expressionism.

ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG

I first met Andy, very shyly, on somebody’s back porch in mid-Manhattan with D—Emile de Antonio. D Antonio had already been instrumental to Andy in a number of ways: he convinced him that he had the courage and the talent to give up his commercial-art success. Andy had a kind of facility which I think drove him to develop and even invent ways to make his art so as not to be cursed by that talented hand. His works are like monuments to his trying to free himself of his talent. Even his choice of subject matter is to get away from anything easy. Whether it’s a chic decision or a disturbing decision about which objects he picks, it’s not an aesthetic choice. And there’s strength in that.

D was also there to console Andy in the beginning, because it’s a big change to move from being a top illustrator into

“I

don’t know if this is art or not.” D stuck by him and exposed his work for the first time to people who were seriously involved in art—gallery owners and a few museum people—and Andy became a phenomenon.

GEORGE SEGAL

The first time I saw Andy’s paintings—strange comic-strip paintings—Lichtenstein had just had his showing at Leo Castelli’s gallery. We said, “What the heck is this?

Two

guys involved with comic strips.” Then the next paintings I saw were Andy’s repetitions of dollar bills. We were amused by that because this Japanese girl Yayoi Kusama was already at the Green Gallery with her repetitions of penises. So such ideas were in the air: the notion of repetition, of serial. Fine. When the dust finally settled, the one who said it best would be the one with the most conviction to deal with the idea.

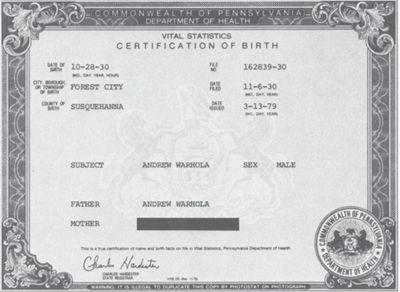

This is the document the State of Pennsylvania provided when asked for the birth certificate of Andrew Warhola, born in 1930.

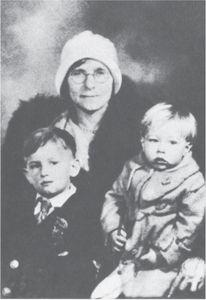

Mrs. Julia Warhola with two of her sons