Educating Ruby (3 page)

Authors: Guy Claxton

For Tom there is a real feeling of having been rendered conservative and brittle by his, apparently successful, education. It was the same for Bill who went to Oxford to study English

literature, where he discovered he had been taught how to outwit the A level examiner rather than to work his way into a difficult novel or poem and then articulate his

own

opinions.

For other people (like Annie’s mum, who sent us her daughter’s sad reflections) their worries are more about a school culture that is callous or indifferent to their children’s feelings, interests and anxieties. It’s no use telling Annie to ‘buck up’ and ‘stop being babyish’. She has a perfect right to her own, rather mature, concerns about animal cruelty. If she is being told to ‘toughen up’, and to deny her own moral sensibilities, then her teacher is unreasonably taking sides in a serious ethical debate, and Annie is being told that her qualms and reactions are invalid. Many parents see their kind, sensitive children being brutalised by the culture of school. Bullying does not need to be overt and physical, although it often is. Children can be very unkind and cliquish, and it is the job of adults to moderate those effects. Annie certainly should not feel she has to become a “fashion freak” in order to have any friends. She is trying to toughen up and hold her ground, but when you are 11 you can do with some support.

Annie was lucky not to go down the same route as Chloe who started self-harming when she was just 12 as a way of coping with being unhappy at school. In an interview in

The Independent

in October 2013, Chloe says, “One day in class I dug my nails into my arm to stop me crying, and I was surprised by how much the physical pain distracted me from the emotional pain. Before long I was regularly scratching myself, deeper each time.” In 2012–2013, over 5,000 10 to 14-year-olds were treated by the NHS for self-harm, a rise

of 20% on the previous year. Many of their worries stemmed from school.

2

Here are another couple of experiences.

My daughter was like some spirally shape that was being pushed into a square box, and it was soul destroying. I’d take this gorgeous little girl to school, and then I’d pick up this really deflated person. She’s quite creative and dreamy. She’d look out the window, see a cloud and make up a story, but the teachers would shout at her to focus on her work … She became more insecure, more deflated, she cried more. She’d always been a good sleeper – she started waking at night. She became much less confident. She gets so over-tired by the workload that she kind of zones out. So she’s not having much happy awake time … and that’s no way to live.

Sandy, mother of a child now

in a London secondary school

As a parent you want your child to feel happy, safe emotionally, to enjoy themselves. When you see your child going into negative spirals, it is highly exhausting … What really did it for me was when she was looking out of the window, looking devastated, and she saw a rock that had cracked, and she said, “That’s how I feel; I’m broken inside.”

Pippa, mother of a Year 5 girl

in a London primary school

School leavers ‘unable to function in the workplace’

More than four in 10 employers are being forced to provide remedial training in English, maths and IT amid concerns teenagers are leaving school lacking basic skills, it emerged today.

3

It’s not just parents (and many teachers) who are unhappy with the schooling system. Variants of the headline above can be found in many British newspapers today as employers find that the ‘residues’ with which young people emerge from school at 16 or 19 do not include the necessary basic skills to cope in the workplace. In 2012, the employers’ organisation, the Confederation of British Industry (CBI), produced a thoughtful report,

First Steps: A New Approach For Our Schools

. In it they articulate two strong arguments.

The first calls for the development of a clear, widely owned and stable statement of the outcomes that all schools are committed to delivering. These, the report argues, should “go beyond the merely academic, into the behaviours and attitudes schools should foster in everything they do”.

4

This statement should be the benchmark against which we judge all new policy ideas, schools and the structures we set

up to monitor them. Are there good reasons for supposing that these modifications will enhance the desired outcomes? If not, go back to the drawing board. The report notes that “in the UK we have often set out aspirational goals [for education] … but we have rarely been clear about how the system will deliver them”, or about how they are to be assessed. “[D]elivery has been judged by an institutional measure – exam results – that is often not well linked to the goals set out at the political level.”

5

The second concern in

First Steps

is the conspicuous lack of engagement by parents and the wider community in schooling. If parents do not feel that they are involved in a partnership with a school that has their child’s best interests at heart, or are not confident that they have a shared understanding of what those best interests are, children’s education is bound to suffer. Professor John Hattie’s research, which the report quotes, has shown that “the effect of parental engagement over a student’s school career is equivalent to adding an extra two to three years to that student’s education”.

6

There is a consequent call for the adoption by schools of a strategy for fostering parental engagement and wider community involvement, including links with business. We’ll go more deeply into the CBI’s thoughtful argument about how schools need to change in

Chapter 5

.

It is worth noting that this call for schools to do more in the way of developing habits and attitudes, and engaging with communities, is not coming from fringe groups of ‘swivel-eyed loons’ or ‘bleeding-heart liberals’. It is coming from one of the most hard-nosed, well-informed organisations in British culture. They are certainly not members of

what previous Secretary of State for Education Michael Gove so dismissively referred to as ‘The Blob’ – a hundred senior education scholars who have devoted much of their lives to trying to understand and improve a really complex system rather than settling for simplistic and antiquated nostrums.

Indeed, within the professional circles of people who know and care about the state of our schools, there is almost universal concern – not because they are politically extreme in any direction but because they know, first hand, what a mixed blessing education can turn out to be. Many school leaders, for example, are not happy with the status quo. Two current campaigns are illustrative of this. The first is called the Great Education Debate, led by one of the two main head teacher professional associations, the Association of School and College Leaders (ASCL). The other is called Redesigning Schooling, led by The Schools Network (the organisation of which Tom Middlehurst is director of research). We explore these ideas in more detail in

Chapter 5

. You can decide for yourselves whether what they are saying mirrors your own concerns.

University departments and colleges of education are full of people trying to improve the lot of your children. Of course, some of them may have strange or radical ideas about what this means, but many are serious scholars who try to see more deeply, and read the evidence more dispassionately, than politicians and journalists are prone to do.

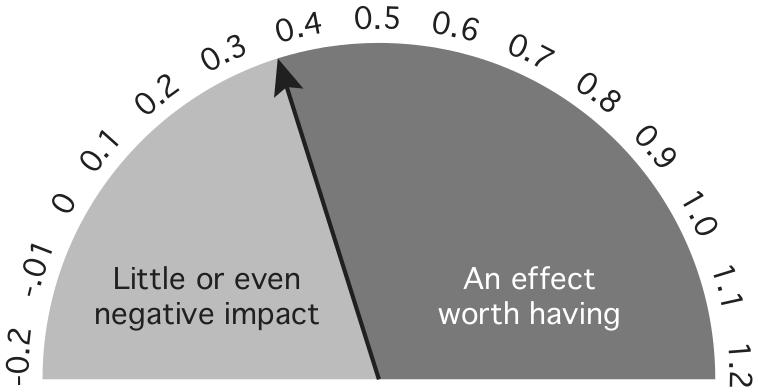

John Hattie has recently been hugely successful at making complex research accessible to teachers. This has been achieved partly through his painstaking analysis of the research, partly by lucid writing, and especially by using simple ‘dashboard’ images, like the one opposite, which make it very easy to compare the size of the effect that

different teaching methods have on students’ examination performance. (Statistically, any effect size above 0.4 on the scale is worth having. Below that, the benefits for students’ achievements are trivial or even sometimes negative.)

His work has generated some surprises. According to the research, grouping students by ‘ability’ – the kind of setting that traditionalists like so much – has an effect size of just 0.12.

7

Top sets benefit a little, while lower sets do worse than they would if they had not been segregated. If you care about everyone, not just the designated ‘winners’, this is an inconvenient truth. Reducing class sizes from 30 to 20 has almost no effect – and it is very expensive – unless, that is, you take this reduction as an opportunity to teach in a different way. Carry on teaching the 20 in the same way you taught the 30 and you might just as well set fire to a big pile of £20 notes. It is the nature of teaching itself that makes the big difference, not tinkering with structural features like the way children are batched, but you would never learn

that from most of what passes for debate in the media and in parliament.

There are a wide variety of issues that concern parents, educators and employers more broadly. In different ways, and with different emphases, parents and employers share a host of concerns about the big issues besetting us today, many of which raise questions about education. These include such questions as:

●

If the internet is both a force for good and for innovation, and an unreliable source of information and fraught with opportunities for cyber-bullying, how should we regulate and educate young people to be both safe and adventurous?

●

Do we have to accept that the decline of reading for pleasure is the result of living in an e-world? How should schools balance surfing and gaming with the encouragement to get lost for hours in a gripping book?

●

Are children, at root, ‘little savages’, inherently naughty and lazy, as some of the Victorians believed, who just have to be trained and disciplined, made to do boring and difficult things that seem pointless, and punished if they don’t comply ‘for their own good’, in order to civilise them? Or do they learn self-control better in other, less draconian, ways?

●

How can we promote religious tolerance in an increasingly war-scarred world? What can schools do to immunise young people against the torrent of violent

propaganda they can find on the web at a click of a mouse?

●

Is climate change an inconvenient fact requiring us to change our habits, or an example of bad science? Is fiddling around trying to ‘balance’ chemical equations a necessary preliminary to engaging with this question, or a distraction?

There is a huge amount of discussion and debate about education these days. Much of it quickly gets technical and statistical and becomes hard to follow; and much of it is fuelled by passionately held beliefs, largely based on ‘what worked (or didn’t work) for me’, generating more heat than light. We all have views because we all went to school, so we think we are experts on the topic. We are all – or nearly all – honourable, well-meaning people who wish the best for the children in our care. But we can’t all be right. Should we go back to the past, to strict discipline and three-hour written exams, to hard subjects like Latin and algebra that train children’s minds in the arts of rationality and retention? Or should we push on to a new future of demanding project work and self-expression, collaboration and problem-solving, continuous assessment and portfolios?

Both of us remember at school having to learn a long poem by Macaulay about a battle for a Roman bridge. One stanza went:

Those behind cried “Forward!”

And those before cried “Back!”

And backward now and forward

Wavers the deep array;

And on the tossing sea of steel,

To and fro the standards reel;

And the victorious trumpet-peal

Dies fitfully away.

It feels like that in the battle for education at the moment. Let’s take a closer look at what the battling forces believe: what is inscribed on their different ‘standards’.

1

Khalil Gibran, On Children, in

The Prophet

(New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1923).

2

Kate Hilpern, Why do children self-harm?,

The Independent

(8 October 2013). Available at:

http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/

health-and-families/features/why-do-so-many-

children-selfharm-8864861.html

.

3

Graeme Paton, School leavers ‘unable to function in the workplace’,

The Telegraph

(11 June 2012). Available at:

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/education

/educationnews/9322525/School-leavers-

unable-to-function-in-the-workplace.html

.

4

CBI,

First Steps: A New Approach For Our Schools

(London: CBI, 2012). Available at:

http://www.cbi.org.uk/media/1845483/

cbi_education_report_191112.pdf

.

5

CBI,

First Steps

.

6

John Hattie,

Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement

(London: Routledge, 2008).

7

See Hattie,

Visible Learning

.