Eight Little Piggies (20 page)

Read Eight Little Piggies Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

2. The textbook detractors assume that Ussher’s effort involved little more than adding up ages and dates given directly in the Old Testament—thus implying that his work was only an accountant’s act of simple, thoughtless piety. Another textbook—we are now up to seven—states that Ussher’s 4004 was “a date reconstructed from adding up the ages of people named in the lineages of the scripture.” But even a cursory look at the Bible clearly shows that no such easy solution is available, even under the assumption of inerrancy. You can add the early times, from creation up to the reign of Solomon—for the requisite information is provided by an unbroken male lineage supplying the key datum of father’s age at the birth of a first son. But this easy route cannot be carried forward into the several hundred years of the kingdom, from Solomon’s reign to the destruction of the Temple and the Babylonian captivity—for here we are only given the lengths of rule for kings, and several frustrating ambiguities (including overlaps or co-regencies of a king and his successor) were widely acknowledged but not easily resolved. Finally, how can you use the Old Testament to reach the crucial birthday of Christ and thus connect the older narrative to the present? For the Old Testament stops in the period of Ezra and Nehemiah, the fifth century

B.C.

in Ussher’s chronology.

James Barr explains the problems and complexities in an excellent article, “Why the World Was Created in 4004

B.C.

: Archbishop Ussher and Biblical Chronology” (see bibliography). He divides the chronological enterprise into three periods, each with characteristic problems, as mentioned above. You can add up during the first period (creation to Solomon), but which text do you use? The ages in the Septuagint

*

are substantially longer and add more than 1,000 years to the date of creation. Ussher solved this dilemma by using the Hebrew Bible and ignoring the alternatives.

In the second period, you really have to struggle to establish a coherent time line through the period of the kings. You feint and shift, try to correlate the dates given for the two kingdoms of Israel and Judah, then attempt to link in the few ages given for events other than beginnings and ends of reigns. The result, with luck and adjustment, is a coherent network of mutually supporting times.

For the third period of more than 400 years from Ezra and Nehemiah to the birth of Jesus you cannot use the Bible at all—for no information exists. Ussher and all other chronologists therefore tried to link a known event in the period of kings with a datable episode in another culture—and then to use the timetables of other peoples until another lateral feint could be made back into the New Testament. Ussher proceeded by correlating the death of the Chaldean king Nebuchadnezzar II with the thirty-seventh year of the exile of Jehoiachin (as stated in 2 Kings 25:27). (Nebuchadnezzar was, of course, prominent in Jewish history for conquering Jerusalem in 586

B.C.

and deporting its prominent citizens—the so-called Babylonian captivity.) Ussher could then calculate through the Chaldean and the subsequent Persian records, eventually reaching the period of Roman rule and the birth of Jesus.

3. But where did Ussher get October 23, 4004? Surely, neither the Bible nor any other source gives a specific date, even if you can estimate the year. Was this date, at least, a bow to dogma, even if the rest of the chronology has more scholarly roots?

No, not dogma, but a different style of interpretive argument—one based on symbol and eschatology rather than listed chronology. (This style cannot be labeled as dogma, if only because each point became a subject of lively disagreement and fierce debate among scholars. No resolution was ever obtained, so the church obviously imposed no answer ex cathedra.)

First of all, the date 4004 coordinates comfortably with the most important of chronological metaphors—the common comparison of the six days of God’s creation with 6,000 years for the earth’s potential duration: “But, beloved, be not ignorant of this one thing, that one day is with the Lord as a thousand years, and a thousand years as one day” (2 Peter 3:8). Under this widely accepted scheme, the earth was created 4,000 years before the birth of Christ and could endure as much as 2,000 years thereafter (a proposition soon to be tested empirically and, we all hope, roundly disproved!).

But why 4004 and not an even 4000

B.C.

? By Ussher’s time, chronologists had established an error in the

B.C.

to

A.D.

transition, for Herod died in 4

B.C.

—and if he truly talked to the Magi, feared the star, and ordered the slaying of the innocents, then Jesus could not have been born after 4

B.C.

(an oxymoronic statement, but acceptable as a testimony to increasing knowledge).

Thus, if Jesus was born in 4

B.C.

, eschatological tradition should fix the date of creation at 4004

B.C.

, without any need for complex, sequential calculation of genealogies. This situation must inspire a nasty suspicion that Ussher “knew” the necessity of 4004

B.C.

right from the start and then jiggered the figures around to make everything come out right. Barr, of course, considers this possibility seriously but rejects it for two reasons. First, Ussher’s chronology extends out to several volumes and 2,000 pages of text and seems carefully done, without substantial special pleading. Second, the death of Herod in 4

B.C.

doesn’t establish the birth of Jesus in the same year. Herod became king of Judea (Roman puppet would be more accurate) in 37

B.C.

—and Jesus might have been born at other times in this thirty-three-year interval. Moreover, other traditions argued that the 4,000 years would run from creation to Christ’s crucifixion, not to his birth—thus extending the possibilities to

A.D.

33. By these flexibilities, creation could have been anywhere between 4037

B.C.

(4,000 years to the beginning of Herod’s reign) and 3967

B.C.

(4,000 years to the Crucifixion). Four thousand four is in the right range, but certainly not ordained by symbolic tradition. You still have to calculate.

But what about October 23? Here, chronology cannot help. Many scholars, from the Venerable Bede to the great astronomer Johannes Kepler, argued for spring as an appropriate season for birth and the chosen time of Babylonian, Chaldean, and other ancient chronologies. Others, including Jerome, Josephus, and Ussher, favored fall, largely because the Jewish year began then, and Hebrew scriptures formed the basis of chronology.

Now an additional problem must be faced. The Jewish chronology is based on lunar months and therefore very hard to correlate with a standard solar calendar. Ussher, recognizing no basis for a firm calibration, therefore decided to establish creation as the first Sunday following the autumnal equinox. (Sunday was an obvious choice, for God created in six days and rested on the seventh, and the Jewish Sabbath falls on Saturday.)

But if creation occurred near the autumnal equinox, why October 23, more than a month from the current date? For this final piece of the puzzle, we need only recognize that Ussher was still using the old Julian (Roman) calendar. The Julian system was very similar to our own, but for one apparently tiny difference—it did not suppress leap years at the century boundaries. (Not everyone knows that our present system—which keeps more accurate time than the Julian—omits leap years at all century transitions not divisible by 400. Thus, 1700, 1800, and 1900 were not leap years, but 1600 was and 2000 will be.) This difference seems tiny, but errors accumulate over millennia. By 1582, the discrepancy had become sufficiently serious that Pope Gregory XIII proclaimed a reform and established the system that we still live by—called, in his honor, the Gregorian calendar. He dropped the ten days that had accumulated from the “extra” leap years at century boundaries in the Julian system (this was done by the clever device of allowing Friday, October 15, to follow Thursday, October 4, in 1582).

We now enter the religious tensions of the time. Recall Ussher’s fulminations against popery, an attitude shared by his Anglican brethren in charge. The Gregorian reform smelled like a Romish plot, and Ussher’s contemporaries would be damned if they would accept it. (England and the American colonies finally succumbed to rationality and instituted the Gregorian reform in 1752. This delay, by the way, is responsible for the ambiguity in George Washington’s birth, sometimes given as February 11 and sometimes as February 22, 1732. He was born under the Julian calendar, and eleven days, rather than ten, had to be dropped by this later time.) In any case, if the Julian discrepancy accounted for ten extra days in the 1,600 or so years between its institution and the Gregorian reform, Ussher realized that the disparity would amount to just over thirty days for the additional time from 4004

B.C.

—thus fixing the creation at October 23, rather than about two-thirds through September, as by our present calendar.

One final point. Why high noon on the day of creation? The inception of Genesis reads:

In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. And God said, Let there be light….

Now you cannot have days without alternations of light and darkness, so Ussher began chronology with the creation of light, which he fixed, for no given reason, at high noon. He wrote, “In ipse primi diei medio creata est lux” (In the middle of the first day, light was created).

But what about the phrases in Genesis that precede the creation of light? Here we encounter an old exegetical problem: Does the text present an epitome of the whole process in these lines, or does it say that God made matter before creating light? Ussher accepted the latter reading and argued that a creation of matter “without form and void” took place during the night before the creation of light. Thus, a precreation, a slipping of material into place, occurred on the night of October 22—yielding several “temporary hours” (Ussher’s words) before the overt creation of light on October 23.

4. Ussher’s chronology is a work within the generous and liberal tradition of humanistic scholarship, not a restrictive document written to impose authority. As Barr notes, Ussher’s

Annales

presents a chronology for all human history (meaning Western history, for he knew no other well enough), from the creation—and you must remember that humans were made five days thereafter, so earthly history is, essentially, human history—to the fall of Jerusalem in

A.D.

70. Barr writes:

It is a great mistake, therefore, to suppose that Ussher was simply concerned with working out the date of creation: this can be supposed only by those who have never looked into its pages…. The

Annales

are an attempt at a comprehensive chronological synthesis of all known historical knowledge, biblical and classical…. Of its volume only perhaps one sixth or less is biblical material.

Socrates told us to know ourselves, and no datum can be more important for humanism than an accurate chronology serving as a framework for the epic of our cultures, our strivings, our failures, and our hopes.

The figure of Ussher that begins this article comes from the only work of his that I own—a comprehensive catechism prepared for children and their families, entitled

A body of divinity: or, the sum and substance of Christian religion

. Catechisms may simplify, but they have the virtue of laying basic belief right on the line, without the hemming and hedging so intrinsic to academic texts.

I was delighted by Ussher’s defense of his chronology in this catechism—simple words that illustrate the basic humanism of his enterprise. How do we know about creation? he asks—and responds: “Not only by the plain and manifold testimonies of Holy Scripture, but also by light of reason well directed.” His main quarrel, we note, is not with other timings of the human epic, but with Aristotle’s ahistorical notion of eternity (see previous essay for discussion of Halley’s similar primary concern). “What say you then to Aristotle, accounted of so many the Prince of Philosophers; who laboreth to prove that the world is eternal.” Ussher answers his own question by defending God’s majesty against a mere unmoved mover of eternal matter, for Aristotle “spoileth God of the glory of his Creation, but also assigneth him to no higher office than is the moving of the spheres, whereunto he bindeth him more like to a servant than a lord.”

I close with a final plea for judging people by their own criteria, not by later standards that they couldn’t possibly know or assess. We castigate Ussher for making the creation so short—a mere six days, where we reckon billions for evolution. But Ussher fears that six days might seem too long in the opinion of his contemporaries, for why should God, who could do all in an instant, so spread out his work? “Why was he creating so long, seeing he could have perfected all the creatures at once and in a moment?” Ussher gives a list of answers, but one caught my attention both for its charm and for its incisive statement about the need for sequential order in teaching—as good a rationale as one could ever devise for working out a chronology in the first place! “To teach us the better to understand their workmanship; even as a man which will teach a child in the frame of a letter, will first teach him one line of the letter, and not the whole letter together.”

I OWN MANY OLD

and beautiful books, classics of natural history bound in leather and illustrated with hand-colored plates. But no item in my collection comes close in personal value to a modest volume, bound in gray cloth and published in 1892:

Studies of English Grammar

, by J. M. Greenwood, Superintendent of Schools in Kansas City. The book belonged to my grandfather, a Hungarian immigrant. He wrote on the title page, in an elegant European hand: “Prop. of Joseph A. Rosenberg, New York.” Just underneath, he added in pencil the most eloquent of all possible lines: “I have landed. Sept. 11, 1901.”

Papa Joe died when I was thirteen, before I could properly distill his deepest experiences, but long enough into my own ontogeny for the precious gifts of extensive memory and lasting influence. He was a man of great artistic sensibility and limited opportunity for expression. I am told that he sang beautifully as a young man, though increasing deafness and a pledge to the memory of his mother (never to sing again after her death) stilled his voice long before my birth. He never used his remarkable talent for drawing in any effort of fine arts, though he marshaled these skills to rise from cloth-cutting in the sweatshops to middle-class life as a brassiere and corset designer. (The content of his chosen expression titillated me as a child, but I now appreciate the primary theme of economic emancipation through the practical application of artistic talent). Yet, above all, he expressed his artistic sensibilities in his personal bearing—in elegance of dress (a bit on the foppish side, perhaps), grace of movement, beauty of handwriting, ease of mannerism.

Sadly, I have no snapshot of Papa Joe and me. But here he is with my cousin Adele, impeccably dressed as always.

I well remember one manifestation of this rise above the ordinary, both because we repeated the act every week and because the junction of locale and action seemed so incongruous, even to a small child of five or six. Every Sunday morning, Papa Joe and I would take a stroll to the corner store on Queens Boulevard to buy the paper and a half-dozen bagels. We then walked to the great world-class tennis stadium of Forest Hills, where McEnroe and his ilk still cavort. A decrepit and disused side entrance sported a rusty staircase of three or four steps. With his unfailing deftness, Papa Joe would take a section of the paper that we never read and neatly spread several sheets over the lowermost step (for the thought of a rust flake or speck of dust in contact with his trousers filled him with horror). We would then sit down and have the most wonderful man-to-man talk about the latest baseball scores, the rules of poker, or the results of the Friday night fights.

I retain a beautiful vision of this scene: The camera pans back and we see a tiny staircase, increasingly dwarfed by the great stadium. Two little figures sit on the bottom step—a well-dressed elderly man gesturing earnestly, a little boy listening with adoration.

Certainty is both a blessing and a danger. Certainty provides warmth, solace, security, an anchor in the unambiguously factual events of personal observation and experience. I know that I sat on those steps with my grandfather because I was there, and no external power of suggestion has ever played havoc with this most deeply personal and private experience.

But certainty is also a great danger, given the notorious fallibility—and unrivaled power—of the human mind. How often have we killed on vast scales for the “certainties” of nationhood and religion? How often have we condemned the innocent because the most prestigious form of supposed certainty—eyewitness testimony—bears all the flaws of our ordinary fallibility?

Primates are visual animals par excellence, and we therefore grant special status to personal observation, to being there and seeing directly. But all sights must be registered in the brain and stored somehow in its intricate memory. And the human mind is both the greatest marvel of nature and the most perverse of all tricksters: Einstein and Loge inextricably combined.

This special (but unwarranted) prestige accorded to direct observation has led to a serious popular misunderstanding about science. Since science is often regarded as the most objective and truth-directed of human enterprises, and since direct observation is supposed to be the favored route to factuality, many people equate respectable science with visual scrutiny—just the facts ma’am, and palpably before my eyes. But science is a battery of observational and inferential methods, all directed to the testing of propositions that can, in principle, be definitely proven false. A restriction of compass to matters of direct observation would stymie the profession intolerably. Science must often transcend sight to win insight. At all scales, from smallest to largest, quickest to slowest, many well-documented conclusions of science lie beyond the strictly limited domain of direct observation. No one has ever seen an electron or a black hole, the events of a picosecond or a geological eon.

One of the phoniest arguments raised for rhetorical effect by “creation scientists” tried to deny scientific status to evolution because its results take so much time to unfold and therefore can’t be seen directly. But if science required such immediate vision, we could draw no conclusions about any subject that studies the past—no geology, no cosmology, no human history (including the strength and influence of religion) for that matter. We can, after all, be reasonably sure that Henry V prevailed at Agincourt even though no photos exist and no one has survived more than five hundred years to tell the tale. And dinosaurs really did snuff it tens of millions of years before any conscious observer inhabited our planet. Evolution suffers no special infirmity as a science because its grandest events took so long to unfold during an unobservable past.

Moreover, eyewitness accounts do not deserve their conventional status as ultimate arbiters even when testimony of direct observation can be marshaled in abundance. In her sobering book,

Eyewitness Testimony

(1979), Elizabeth Loftus debunks, largely in a legal context, the notion that visual observation confers some special claim for veracity. She identifies three levels of potential error in supposedly direct and objective vision: misperception of the event itself, and the two great tricksters of passage through memory before later disgorgement—retention and retrieval.

In one experiment, for example, Loftus showed 40 students a three-minute videotape of a classroom lecture disrupted by 8 demonstrators (a relevant subject for a study from the early 1970s!). She gave the students a questionnaire and asked half of them, “Was the leader of the 12 demonstrators…a male?” and the other half, “Was the leader of the 4 demonstrators…a male?” One week later, in a follow-up questionnaire, she asked all the students, “How many demonstrators did you see entering the classroom?” Those who had previously received the question about 12 demonstrators reported seeing an average of 8.9 people; those told of 4 demonstrators claimed an average of 6.4. All had actually seen 8, but formed a later judgment as a compromise between their actual observation and the largely subliminal power of suggestion in the first questionnaire.

People can even be induced to “see” totally illusory objects. In another experiment, Loftus showed a film of an accident, followed by a misleading question: “How fast was the white sports car going when it passed the barn while traveling along the country road?” (The film showed no barn, and a control group received a more accurate question: “How fast was the white sports car going while traveling along the country road?”) A week later, 17 percent of students in the first group stated that they had seen the nonexistent barn; only 3 percent of the controls reported a barn.

Thus, we are easily fooled on all fronts of both eye and mind: seeing, storing, and recalling. The eye tricks us badly enough; the mind is even more perverse. What remedy can we possibly suggest but constant humility, and eternal vigilance and scrutiny? Trust your memory as you would your poker buddy (one of my grandfather’s mottos from the steps).

With this principle in mind, I went searching for those steps last year after more than thirty years of absence from my natal turf. I exited the subway at 67th Avenue, walked to my first apartment at 98–50, and then set off on my grandfather’s route for Queens Boulevard and the tennis stadium.

I was walking in the right direction, but soon realized that I had made a serious mistake. The tennis stadium stood at least a mile down the road, too far for those short strolls with a bag of bagels in one hand and a five-year-old boy attached to the other. In increasing puzzlement, I walked down the street and, at the very next corner, saw the steps and felt the jolt and flood of memory that drives our

recherches des temps perdus

.

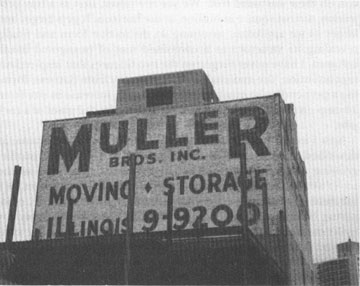

My recall of the steps was entirely accurate—three modest flagstone rungs, bordered by rusty iron railings. But the steps are not attached to the tennis stadium; they form the side entrance to a modest brick building, now crumbling, padlocked, and abandoned, but still announcing its former use with a commercial sign, painted directly on the brick in the old industrial style—“Muller Bros. Moving & Storage”—with a telephone number below from the age before all-digit dialing: ILlinois 9-9200.

Obviously, I had conflated the most prominent symbol of my old neighborhood, the tennis stadium, with an important personal place, and had constructed a juxtaposed hybrid for my mental image. Yet my memory of the tennis stadium soaring above the steps remains strong, even now in the face of conclusive correction.

The side wall of Muller Bros. as it appears today with its painting in the old industrial style.

Photograph by Eleanor Gould

.

I might ask indulgence on the grounds of inexperience and relative youth, for my failure as an eyewitness at the Muller Bros. steps. After all, I was only an impressionable lad of five or so, when even a modest six-story warehouse might be perceived as big enough to conflate with something truly important.

But I have no excuses for a second story. Ten years later, at a trustable age of fifteen, my family made a western trip by automobile: I have specially vivid memories of an observation at Devil’s Tower, Wyoming (the volcanic plug made most famous as a landing site for aliens in

Close Encounters of the Third Kind

). We approach from the east. My father tells us to look for the tower from tens of miles away, for he has read in a guidebook that it rises, with an awesome near-verticality, from the dead-flat Great Plains, and that pioneer families used the tower as a landmark and beacon on their westward trek. We see the tower, first as a tiny projection, almost square in outline, at the horizon. It gets larger and larger as we approach, assuming its distinctive form and finally revealing its structure as a conjoined mat of hexagonal basalt columns. I have never forgotten the two features that inspired my rapt attention: the maximal rise of verticality from flatness, forming a perpendicular junction, and the steady increase in size from a bump on the horizon to a looming, almost fearful giant of a rock pile.

Now I know, I absolutely

know

that I saw this visual drama, as described. The picture in my mind of that distinctive profile, growing in size, is as strong as any memory I possess. I

see

the tower as a little dot in the distance, as a midsized monument, as a full field of view. I have told the story to scores of people, comparing this natural reality with a sight of Chartres as a tiny toy tower twenty miles from Paris, growing to the overarching symbol and skyline of its medieval city.

In 1987, I revisited Devil’s Tower with my family—the only return since my first close encounter thirty years before. I planned the trip to approach from the east, so that they would see the awesome effect—and I told them my story, of course.

In the context of this essay, my dénouement will be anticlimactic in its predictability, however acute my personal embarrassment. The terrain around Devil’s Tower is mountainous; the monument cannot be seen from more than a few miles away in any direction. I bought a booklet on pioneer trails westward, and none passed anywhere near Devil’s Tower. We enjoyed our visit, but I felt like a perfect fool. Later, I checked my old log book for that high school trip. The monument that rises from the plain, the beacon of the pioneers, is Scottsbluff, Nebraska—not nearly so impressive a pile of stone as Devil’s Tower.