Eight Pieces of Empire (21 page)

Read Eight Pieces of Empire Online

Authors: Lawrence Scott Sheets

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Russia & the Former Soviet Union, #Former Soviet Republics, #Essays

Democracy is what Azerbaijanis were promised. Instead, their country was falling apart, losing territory to the Armenians, getting caught up in comic-opera wars like the one we were covering, corruption, warlords, crime. Therefore, “democracy” was increasingly associated with simple anarchy.

Adil lamented all of this. He did not believe Communism was a better model for Azerbaijan, and yet neither did he believe that the country was ready for “real” democracy. Ideally, Azerbaijan would have an “Eastern Democracy”—a kind of temporary, benevolent autocracy, headed by a type of “father figure”—similar to those running the new sultan-type states emerging in Central Asia. Most of their leaders were busy building sultanate-type regimes, often based around elaborate if still whimsical cults of personality. As the 1990s progressed, the whimsical part fell off and an overt, heavy sense of dictatorship and repression took over in almost all of them.

Adil had just returned from Turkmenistan, across the Caspian Sea from Azerbaijan. “There is something I would call Eastern Democracy,” said Adil. He gave an example, noting that the quirky leader of Turkmenistan, Saparmurat Niyazov (who had renamed himself Turkmenbashi, or “Head of All Turkmen”), provided his four million subjects with free natural gas, salt, and other basics. (These were the early “soft” years of Turkmenbashi’s post-Soviet reign; however, later he would evolve into one of the most erratic, repressive leaders in the world.)

“It is a kind of social contract,” Adil added. He obviously found the sense of order familiar and comforting in a way, compared with the constant battlefield losses to the Armenians and the ongoing, ludicrous “civil war” we were observing in the steppe and desert north of Baku.

“In Eastern Democracy, the strong man takes care of the needs of the people. There is law and order,” argued Adil. “It is a transitional way to democracy, because we are in a transitional situation. Our people are used to a patriarchic system, to having a ‘big man,’ and that’s what they want now.”

While Adil’s ketchup monologue continued, we saw the first APCs parked along the road to Shemakhi and a few dozen soldiers. We stopped

the car in a dusty clearing at the side of the road and asked which side of the war they were on. These were government soldiers, it turned out. “Where’s the front line? Where are Surat’s people?” asked Adil.

“Right up there.” One of the government guys pointed to a nearby hill. There were no more than a hundred yards separating the two sides. No trenches. No real fortifications. Nothing but a hundred yards of air.

There was also a conspicuous lack of any noticeable tension between the sides, at least in this place. Aside from one government type taking a quick peek though some binoculars at the “rebels,” the sides didn’t seem to be paying much attention to each other.

Having nothing much else to do, the government group decided to show its hospitality by giving us a ride on their APC through the rocky, desertlike terrain so that we could get a look at the lay of the land. We left the roadway and started down an incline. Soon we were cruising down a dusty trail. I sat atop the APC while Adil filmed through a periscope from inside.

We drove for about three miles before we approached what looked like some sort of old collective farm building. Nearby there was a square, cement-type block structure. It was a natural well, used for outdoor bathing. The cement slabs blocked our view, but under the fountain of water pouring from a spigot bobbed a woman’s head—she was taking a shower.

Our government soldier friends became instantly distracted and began whistling and hollering. Evidently the driver of the APC was not immune to the charms of the lady’s head of hair, for he had apparently taken his eyes off the terrain in front of him.

There was a gentle jolt, a wiggle of the wheels, and then the right side of the APC gradually began to elevate in a way I knew it should not. As the vehicle started to lurch, I scrambled to get on the high side, grabbing toward one of the wheels now spinning in the air. Then I felt myself falling off, losing consciousness as I hit the ground. When I came to, I could see the APC teetering on its side above me, rocking slowly toward me. The armored vehicle was about to roll over onto my legs.

At the last second, I felt two hands pulling me by the arms along the rocky ground just as the multi-ton hulk of military metal slowly

somersaulted over exactly where I had been lying, its turret digging into the sand. Now on my feet, I embraced the soldier who had saved my life—or at least my legs.

But the soldiers were less worried about me (or doing battle with the rebel foe) than the reaction of their commanding officer should they return to “base” without their APC.

There were eight or nine of us, but I am still amazed at our achievement. Grunting and groaning, we pushed and shoved until finally we managed to prop the APC on its side, and then with another herculean effort, righted it back on its wheels. Rather than congratulate themselves on our success, however, the soldiers then began cursing one another over the damage, waving their fingers and assigning blame. When one seemed to take too much interest in a Kalashnikov propped on a bush, we knew it was time to go.

“Let’s get out of here,” Adil said.

It was a good idea, and I still had my legs.

Leaving our friends and the APC behind, we ascended a sandy ridge and kept walking in the general direction of the road, eventually finding it several miles away from where we had left our driver.

“You Americans don’t really understand. We’re not totally ready for democracy, as you call it,” Adil said, wiping APC soot and sweat from his brow. “I’m not saying we won’t have it eventually. But right now it’s too early. This is chaos, not democracy.”

What Adil really wanted was just a normal life for himself and his family.

Prophetically, Azerbaijan would in the coming years take on some of the elements of an “Eastern Democracy”: The former Communist strongman Heydar Aliyev conceded to some demands of the wool-merchant-cum-warlord Surat Huseinov, including making him prime minister. Within two years, however, Aliyev outmaneuvered Surat, who ended up in prison for several years on charges of coup plotting.

The Heydar Aliyev clan, helped by new oil money, then built an authoritarian system with all the whistles and bells—handing off power to

Heydar’s son Ilham before Heydar’s death, holding sham elections, and engineering the total dominance of the state over most aspects of life.

We got back to the car and continued to the ancient town of Shemakhi, the former capital of Azerbaijan, probably crossing the front several times without knowing it because the sentries were asleep or something. There were a few gun-toting men hanging around the main administration building, and we met a city official inside, who said merely that he “was on the side of peace.” But we had no idea who was in control, and no one seemed to want to tell us.

“Let’s go back to Baku to see who is in power today,” Adil suggested, sarcastically.

“OK,” I said.

Aside from my near death by APC, it had been an enlightening day. A “civil war” that was barely one, the lone government casualty the wrecked piece of military hardware.

INDEED, THE REAL

war was elsewhere, and receiving almost no news coverage because one had to cross the lines of the Shish Kebab War to get there. That real war, of course, was being fought over Karabakh, and during that white-hot summer, Azerbaijan’s battlefield losses to Armenia continued unabated. The most notable loss came in July, when Azerbaijani troops lost the frontline city of Agdam, once home to seventy thousand souls, but already largely abandoned by civilians. The Armenians then carted away doors, window frames, and even the white bricks used to build the houses as war booty.

I made it to within a few miles of Agdam the day after it fell, and saw it burning in the near distance—the fate of all fallen cities in all the Caucasus wars. There, I met the last Azerbaijani unit along the road, a platoon of twenty or so. The commander, distraught and on the edge of a nervous breakdown, insisted on digging up a dead comrade to show me. There was no corpse; only a perfectly flattened head remained, which the by now inconsolable commander pried up with a stick and displayed to

me. He claimed it had been intentionally run over by an Armenian tank as his forces retreated.

I thought of my own narrow escape from getting crushed by the flip-flopping APC outside Shemakhi.

I listened to the commander wail and wave around the head of his friend with Agdam burning in the background, the requisite wave of refugees, cars loaded down with rescued refrigerators, blankets, and mattresses pulling away from the area.

AND I WOULD

have to file again from the chaos of Azerbaijan a few years after the fall of Agdam and the Shish Kebab War, and this time the subject was Adil Bunyatov, my friend and cameraman.

Less than two years after Adil’s dreams of opening a ketchup factory and his soliloquy about “Eastern Democracy” and speculations about whether Azerbaijan might be better off with a little benign dictatorship instead of the chaos that came with gradual moves toward broader political freedoms, the autocratic government of Heydar Aliyev was faced with a new rebellion. Adil went forth to do his job of finding and filming the “front,” which this time took the form of a suburban military barracks in Baku. But unlike the Shish Kebab War of the summer of 1993, this was an all-too-real confrontation pitting Azerbaijani against Azerbaijani, and when the guys with guns on either side of the politic divide fired their weapons, it was in anger and with intent to kill.

When the smoke cleared, dozens of soldiers lay dead; the rogue officer behind the rebellion was allowed to bleed to death on his way to the hospital.

Adil was no longer there to report it. He was killed in the opening blast when a stray bullet struck his jugular. The doctors tried to reassure his family, which included a wife and a son, that his death had probably been very quick and almost painless.

He was the first of my close reporting friends and colleagues to be killed in action.

He would not be the last.

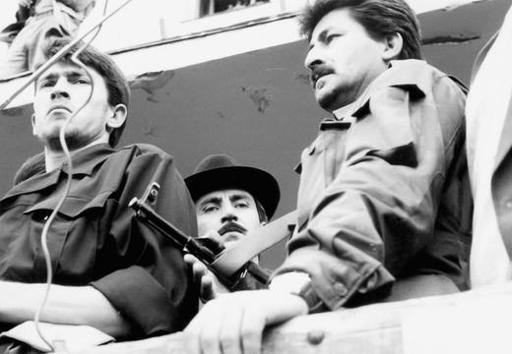

Dudayev addresses rally in Grozny, June 1993.

T

he most tragic thing

about the first Chechen-Russian war was that it took place at all. Until just before it began, almost no journalists or political pundits believed there would be a war—those who had even heard of Chechnya assumed the embattled separatist leader Dzhokhar Dudayev would eventually be toppled by his own people, saving the Russians the trouble.

The reasons that it erupted were, at charitable best, human stupidity on a protozoan level; at worst, they were heinous and recklessly criminal. The decision by the Russian Federation to send in troops was made in a bathhouse by naked, drunken men during a birthday celebration for the country’s defense minister, Pavel Grachev. At first the Russians relentlessly bombed airports around the Chechen capital city, Grozny, to establish a no-fly zone.

Someone forgot to tell them that the Chechen separatists had no planes, except some old Czechoslovak training craft that were practically incapable of getting airborne, let alone dropping a bomb. Once the ground war began, thousands of fresh-faced Russian youth in armored columns without infantry were sent into Grozny without even city maps, getting lost in the maze of sixteen-story residential high-rises in the city center. This made them easy targets for the ragtag Chechen militias, who, armed with grenades and RPGs (rocket-propelled grenades), often laughingly ascended idling Russian tanks, flipped open the hatches, and dropped the explosives inside, turning the crews into shreds of human flesh. The Russian reaction was to carpet-bomb the city, using levels of tonnage that had not been seen since the Allied bombings of Dresden during World War II.

I first came to Chechnya during the summer of 1993, covered most of the war that broke out in 1994, and would return dozens of times over the next decade. Many of the central characters included in the following chapters were killed during the carnage. I often wonder why I am not among their number.