Einstein (25 page)

Authors: Walter Isaacson

Whatever happened added to Mari ’s gloom. Shortly after Einstein died, a writer named Peter Michelmore, who knew nothing of Lieserl, published a book that was based in part on conversations with Einstein’s son Hans Albert Einstein. Referring to the year right after their marriage, Michelmore noted, “Something had happened between the two, but Mileva would say only that it was ‘intensely personal.’ Whatever it was, she brooded about it, and Albert seemed to be in some ways responsible. Friends encouraged Mileva to talk about her problem and get it out in the open. She insisted that it was too personal and kept it a secret all her life—a vital detail in the story of Albert Einstein that still remains shrouded in mystery.”

’s gloom. Shortly after Einstein died, a writer named Peter Michelmore, who knew nothing of Lieserl, published a book that was based in part on conversations with Einstein’s son Hans Albert Einstein. Referring to the year right after their marriage, Michelmore noted, “Something had happened between the two, but Mileva would say only that it was ‘intensely personal.’ Whatever it was, she brooded about it, and Albert seemed to be in some ways responsible. Friends encouraged Mileva to talk about her problem and get it out in the open. She insisted that it was too personal and kept it a secret all her life—a vital detail in the story of Albert Einstein that still remains shrouded in mystery.”

94

The illness that Mari complained about in her postcard from Budapest was likely because she was pregnant again. When she found out that indeed she was, she worried that this would anger her husband. But Einstein expressed happiness on hearing the news that there would soon be a replacement for their daughter. “I’m not the least bit angry that poor Dollie is hatching a new chick,” he wrote. “In fact, I’m happy about it and had already given some thought to whether I shouldn’t see to it that you get a new Lieserl. After all, you shouldn’t be denied that which is the right of all women.”

complained about in her postcard from Budapest was likely because she was pregnant again. When she found out that indeed she was, she worried that this would anger her husband. But Einstein expressed happiness on hearing the news that there would soon be a replacement for their daughter. “I’m not the least bit angry that poor Dollie is hatching a new chick,” he wrote. “In fact, I’m happy about it and had already given some thought to whether I shouldn’t see to it that you get a new Lieserl. After all, you shouldn’t be denied that which is the right of all women.”

95

Hans Albert Einstein was born on May 14, 1904. The new child lifted Mari ’s spirits and restored some joy to her marriage, or so at least she told her friend Helene Savi

’s spirits and restored some joy to her marriage, or so at least she told her friend Helene Savi : “Hop over to Bern so I can see you again and I can show you my dear little sweetheart, who is also named Albert. I cannot tell you how much joy he gives me when he laughs so cheerfully on waking up or when he kicks his legs while taking a bath.”

: “Hop over to Bern so I can see you again and I can show you my dear little sweetheart, who is also named Albert. I cannot tell you how much joy he gives me when he laughs so cheerfully on waking up or when he kicks his legs while taking a bath.”

Einstein was “behaving with fatherly dignity,” Mari noted, and he spent time making little toys for his baby son, such as a cable car he constructed from matchboxes and string. “That was one of the nicest toys I had at the time and it worked,” Hans Albert could still recall when he was an adult. “Out of little string and matchboxes and so on, he could make the most beautiful things.”

noted, and he spent time making little toys for his baby son, such as a cable car he constructed from matchboxes and string. “That was one of the nicest toys I had at the time and it worked,” Hans Albert could still recall when he was an adult. “Out of little string and matchboxes and so on, he could make the most beautiful things.”

96

Milos Mari was so overjoyed with the birth of a grandson that he came to visit and offered a sizable dowry, reported in family lore (likely with some exaggeration) to be 100,000 Swiss francs. But Einstein declined it, saying he had not married his daughter for money, Milos Mari

was so overjoyed with the birth of a grandson that he came to visit and offered a sizable dowry, reported in family lore (likely with some exaggeration) to be 100,000 Swiss francs. But Einstein declined it, saying he had not married his daughter for money, Milos Mari later recounted with tears in his eyes. In fact, Einstein was beginning to do well enough on his own. After more than a year at the patent office, he had been taken off probationary status.

later recounted with tears in his eyes. In fact, Einstein was beginning to do well enough on his own. After more than a year at the patent office, he had been taken off probationary status.

97

THE MIRACLE YEAR:

Quanta and Molecules, 1905

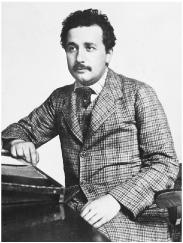

At the Patent Office, 1905

“There is nothing new to be discovered in physics now,” the revered Lord Kelvin reportedly told the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1900. “All that remains is more and more precise measurement.”

1

He was wrong.

The foundations of classical physics had been laid by Isaac Newton (1642–1727) in the late seventeenth century. Building on the discoveries of Galileo and others, he developed laws that described a very comprehensible mechanical universe: a falling apple and an orbiting moon were governed by the same rules of gravity, mass, force, and motion. Causes produced effects, forces acted upon objects, and in theory everything could be explained, determined, and predicted. As the mathematician and astronomer Laplace exulted about Newton’s universe,

“An intelligence knowing all the forces acting in nature at a given instant, as well as the momentary positions of all things in the universe, would be able to comprehend in one single formula the motions of the largest bodies as well as the lightest atoms in the world; to him nothing would be uncertain, the future as well as the past would be present to his eyes.”

2

Einstein admired this strict causality, calling it “the profoundest characteristic of Newton’s teaching.”

3

He wryly summarized the history of physics: “In the beginning (if there was such a thing) God created Newton’s laws of motion together with the necessary masses and forces.” What especially impressed Einstein were “the achievements of mechanics in areas that apparently had nothing to do with mechanics,” such as the kinetic theory he had been exploring, which explained the behavior of gases as being caused by the actions of billions of molecules bumping around.

4

In the mid-1800s, Newtonian mechanics was joined by another great advance. The English experimenter Michael Faraday (1791– 1867), the self-taught son of a blacksmith, discovered the properties of electrical and magnetic fields. He showed that an electric current produced magnetism, and then he showed that a changing magnetic field could produce an electric current. When a magnet is moved near a wire loop, or vice versa, an electric current is produced.

5

Faraday’s work on electromagnetic induction permitted inventive entrepreneurs like Einstein’s father and uncle to create new ways of combining spinning wire coils and moving magnets to build electricity generators. As a result, young Albert Einstein had a profound physical feel for Faraday’s fields and not just a theoretical understanding of them.

The bushy-bearded Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell (1831–1879) subsequently devised wonderful equations that specified, among other things, how changing electric fields create magnetic fields and how changing magnetic fields create electrical ones. A changing electric field could, in fact, produce a changing magnetic field that could, in turn, produce a changing electric field, and so on. The result of this coupling was an electromagnetic wave.

Just as Newton had been born the year that Galileo died, so Einstein

was born the year that Maxwell died, and he saw it as part of his mission to extend the work of the Scotsman. Here was a theorist who had shed prevailing biases, let mathematical melodies lead him into unknown territories, and found a harmony that was based on the beauty and simplicity of a field theory.

All of his life, Einstein was fascinated by field theories, and he described the development of the concept in a textbook he wrote with a colleague: