El Borak and Other Desert Adventures (12 page)

Read El Borak and Other Desert Adventures Online

Authors: Robert E. Howard

“We will be next,” said the third. “The sahibs are dead. Let us load the animals and go away quickly. Better die in the hills than wait like sheep for our throats to be cut.”

A few minutes later they were hurrying eastward through the pines as fast as they could urge the laden beasts.

Of this Gordon knew nothing. When he left the slope below the cave he did not follow the trend of hills as before, but headed straight through the pines toward the lights of Yolgan. He had not gone far when he struck a road from the east leading toward the city. It wound among the pines, a slightly less dark thread in a bulwark of blackness.

He followed it to within easy sight of the great gate which stood open in the dark and massive walls of the town. Guards leaned carelessly on their matchlocks. Yolgan feared no attack. Why should it? The wildest of the Mohammedan tribes shunned the land of the devil worshipers. Sounds of barter and dispute were wafted by the night wind through the gate.

Somewhere in Yolgan, Gordon was sure, were the men he was seeking. That they intended returning to the cave he had been assured. But there was a reason why he wished to enter Yolgan, a reason not altogether tied up with vengeance. As he pondered, hidden in the deep shadow, he heard the soft

clop

of hoofs on the dusty road behind him. He slid farther back among the pines; then with a sudden thought he turned and made his way back beyond the first turn, where he crouched in the blackness beside the road.

Presently a train of laden pack mules came along, with men before and behind and at either side. They bore no torches, moving like men who knew their path. Gordon’s eyes had so adjusted themselves to the faint starlight of the road that he was able to recognize them as Kirghiz herdsmen in their long

cloaks and round caps. They passed so close to him that their body-scent filled his nostrils.

He crouched lower in the blackness, and as the last man moved past him, a steely arm hooked fiercely about the Kirghiz’s throat, choking his cry. An iron fist crunched against his jaw and he sagged senseless in Gordon’s arms. The others were already out of sight around the bend of the trail, and the scrape of the mules’ bulging packs against the branches along the road was enough to drown the slight noises of the struggle.

Gordon dragged his victim in under the black branches and swiftly stripped him, discarding his own boots and

kaffiyeh

and donning the native’s garments, with pistol and scimitar buckled on under the long cloak. A few minutes later he was moving along after the receding column, leaning on his staff as with the weariness of long travel. He knew the man behind him would not regain consciousness for hours.

He came up with the tail of the train, but lagged behind as a straggler might. He kept close enough to the caravan to be identified with it, but not so close as to tempt conversation or recognition by the other members of the train. When they passed through the gate none challenged him. Even in the flare of the torches under the great gloomy arch he looked like a native, with his dark features fitting in with his garments and the lambskin cap.

As he went down the torch-lighted street, passing unnoticed among the people who chattered and argued in the markets and stalls, he might have been one of the many Kirghiz shepherds who wandered about, gaping at the sights of the city which to them represented the last word in the metropolitan.

Yolgan was not like any other city in Asia. Legend said it was built long ago by a cult of devil worshipers who, driven from their distant homeland, had found sanctuary in this unmapped country, where an isolated branch of the Black Kirghiz, wilder than their kinsmen, roamed as masters. The people of the city were a mixed breed, descendants of these original founders and the Kirghiz.

Gordon saw the monks who were the ruling caste in Yolgan striding through the bazaars — tall, shaven-headed men with Mongolian features. He wondered anew as to their exact origin. They were not Tibetans. Their religion was not a depraved Buddhism. It was an unadulterated devil worship. The architecture of their shrines and temples differed from any he had ever encountered anywhere.

But he wasted no time in conjecture, nor in aimless wandering. He went straight to the great stone building squatting against the side of the mountain at the foot of which Yolgan was built. Its great blank curtains of stone seemed almost like part of the mountain itself.

No one hindered him. He mounted a long flight of steps that were at least a hundred feet wide, bending over his staff as with the weariness of a long

pilgrimage. Great bronze doors stood open, unguarded, and he kicked off his sandals and came into a huge hall the inner gloom of which was barely lighted by dim brazen lamps in which melted butter was burned.

Shaven-headed monks moved through the shadows like dusky ghosts, but they gave him no heed, thinking him merely a rustic worshiper come to leave some humble offering at the shrine of Erlik, Lord of the Seventh Hell.

At the other end of the hall, view was cut off by a great divided curtain of gilded leather that hung from the lofty roof to the floor. Half a dozen steps that crossed the hall led up to the foot of the curtain, and before it a monk sat cross-legged and motionless as a statue, arms folded and head bent as if in communion with unguessed spirits.

Gordon halted at the foot of the steps, made as if to prostrate himself, then retreated as if in sudden panic. The monk showed no interest. He had seen too many nomads from the outer world overcome by superstitious awe before the curtain that hid the dread effigy of Erlik Khan. The timid Kirghiz might skulk about the temple for hours before working up nerve enough to make his devotions to the deity. None of the priests paid any attention to the man in the caftan of a shepherd who slunk away as if abashed.

As soon as he was confident that he was not being watched, Gordon slipped through a dark doorway some distance from the gilded curtain and groped his way down a broad unlighted hallway until he came to a flight of stairs. Up this he went with both haste and caution and came presently into a long corridor along which winked sparks of light, like fireflies in a tunnel.

He knew these lights were tiny lamps in the small cells that lined the passage, where the monks spent long hours in contemplation of dark mysteries, or pored over forbidden volumes, the very existence of which is not suspected by the outer world. There was a stair at the nearer end of the corridor, and up this he went, without being discovered by the monks in their cells. The pin points of light in the chambers did not serve to illuminate the darkness of the corridor to any extent.

As Gordon approached a crook in the stair he renewed his caution, for he knew there would be a man on guard at the head of the steps. He knew also that he would be likely to be asleep. The man was there — a half-naked giant with the wizened features of a deaf mute. A broad-tipped tulwar lay across his knees and his head rested on it as he slept.

Gordon stole noiselessly past him and came into an upper corridor which was dimly lighted by brass lamps hung at intervals. There were no doorless cells here, but heavy bronze-bound teak portals flanked the passage. Gordon went straight to one which was particularly ornately carved and furnished with an unusual fretted arch by way of ornament. He crouched there listening

intently, then took a chance and rapped softly on the door. He rapped nine times, with an interval between each three raps.

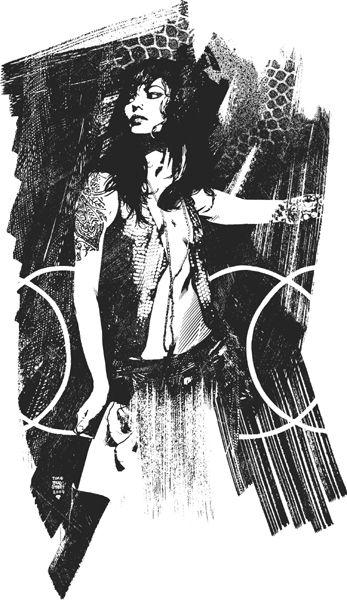

There was an instant’s tense silence, then an impulsive rush of feet across a carpeted floor, and the door was jerked open. A magnificent figure stood framed in the soft light. It was a woman, a lithe, splendid creature whose vibrant figure exuded magnetic vitality. The jewels that sparkled in the girdle about her supple hips were no more scintillant than her eyes.

Instant recognition blazed in those eyes, despite his native garments. She caught him in a fierce grasp. Her slender arms were strong as pliant steel.

“El Borak! I knew you would come!”

Gordon stepped into the chamber and closed the door behind him. A quick glance showed him there was no one there but themselves. Its thick Persian rugs, silk divans, velvet hangings, and gold-chased lamps struck a vivid contrast with the grim plainness of the rest of the temple. Then he turned his full attention again to the woman who stood before him, her white hands clenched in a sort of passionate triumph.

“How did you know I would come, Yasmeena?” he asked.

“You never failed a friend in need,” she answered.

“Who is in need?”

“I!”

“But you are a goddess!”

“I explained it all in my letter!” she exclaimed bewilderedly.

Gordon shook his head. “I have received no letter.”

“Then why are you here?” she demanded in evident puzzlement.

“It’s a long story,” he answered. “Tell me first why Yasmeena, who had the world at her feet and threw it away for weariness to become a goddess in a strange land, should speak of herself as one in need.”

“In desperate need, El Borak.” She raked back her dark locks with a nervously quick hand. Her eyes were shadowed with weariness and something more, something which Gordon had never seen there before — the shadow of fear.

“Here is food you need more than I,” she said as she sank down on a divan and with a dainty foot pushed toward him a small gold table on which were chupaties, curried rice, and broiled mutton, all in gold vessels, and a gold jug of kumiss.

He sat down without comment and began to eat with unfeigned gusto. In his drab camel’s-hair caftan, with the wide sleeves drawn back from his corded brown arms, he looked out of place in that exotic chamber.

Yasmeena watched him broodingly, her chin resting on her hand, her somber eyes enigmatic.

“I did not have the world at my feet, El Borak,” she said presently. “But I had enough of it to sicken me. It became a wine which had lost its savor. Flattery became like an insult; the adulation of men became an empty repetition without meaning. I grew maddeningly weary of the flat fool faces that smirked eternally up at me, all wearing the same sheep expressions and animated by the same sheep thoughts. All except a few men like you, El Borak, and you were wolves in the flock. I might have loved you, El Borak, but there is something too fierce about you; your soul is a whetted blade on which I feared I might cut myself.”

He made no reply, but tilted the golden jug and gulped down enough stinging kumiss to have made an ordinary man’s head swim at once. He had lived the life of the nomads so long that their tastes had become his.

“So I became a princess, wife of a prince of Kashmir,” she went on, her eyes smoldering with a marvelous shifting of clouds and colors. “I thought I knew the depths of men’s swinishness. I found I had much to learn. He was a beast. I fled from him into India, and the British protected me when his ruffians would have dragged me back to him. He still offers many thousand rupees to any who will bring me alive to him, so that he may soothe his vanity by having me tortured to death.”

“I have heard a rumor to that effect,” answered Gordon.

A recurrent thought caused his face to darken. He did not frown, but the effect was subtly sinister.

“That experience completed my distaste for the life I knew,” she said, her dark eyes vividly introspective. “I remembered that my father was a priest of Yolgan who fled away for love of a stranger woman. I had emptied the cup and the bowl was dry. I remembered Yolgan through the tales my father told me when I was a babe, and a great yearning rose in me to lose the world and find my soul. All the gods I knew had proved false to me. The mark of Erlik was upon me —” She parted her pearl-sewn vest and displayed a curious starlike mark between her firm breasts.

“I came to Yolgan as well you know, because you brought me, in the guise of a Kirghiz from Issik-kul. As you know the people remembered my father, and though they looked on him as a traitor, they accepted me as one of them, and because of an old legend which spoke of the star on a woman’s bosom, they hailed me as a goddess, the incarnation of the daughter of Erlik Khan.

“For a while after you went away I was content. The people worshiped me with more sincerity than I had ever seen displayed by the masses of civilization. Their curious rituals were strange and fascinating. Then I began to go further into their mysteries; I began to sense the essence below the formula —” She paused, and Gordon saw the fear grow in her eyes again.

“I had dreamed of a calm retreat of mystics, inhabited by philosophers. I found a haunt of bestial devils, ignorant of all but evil. Mysticism? It is black

shamanism, foul as the tundras which bred it. I have seen things that made me afraid. Yes, I, Yasmeena, who never knew the meaning of the word, I have learned fear. Yogok, the high priest, taught me. You warned me against Yogok before you left Yolgan. Well had I heeded you. He hates me. He knows I am not divine, but he fears my power over the people. He would have slain me long ago had he dared.

“I am wearied to death of Yolgan. Erlik Khan and his devils have proved no less an illusion than the gods of India and the West. I have not found the perfect way. I have found only awakened desire to return to the world I cast away.