Eleanor of Aquitaine (37 page)

Read Eleanor of Aquitaine Online

Authors: Marion Meade

Entry of emperor Conrad III and Louis VII into Constantinople during the Second Crusade, a fifteenth-century miniature from “Grandes chroniques de France.” The artist was mistaken because the two armies entered the city at different times.

Crowned heads of Eleanor and Henry, an engaged capital from the Church of Notre-Dame-du-Bourg near Bordeaux, which now can be seen at the Cloisters in New York. Probably the carved heads date from a progress they made through Aquitaine in 1152.

Left,

the remains of Eleanor’s seal. struck in 1152 shortly after her marriage to Henry, from a charter in the Archives de France

the remains of Eleanor’s seal. struck in 1152 shortly after her marriage to Henry, from a charter in the Archives de France

Statue of Richard I by Marochetti, 1860, outside the House of Lords, London

Tomb effigy of King John at Worcester Cathedral. John was the first Plantagenet king to be buried in England.

King John signing the Magna Charta at Runnymede in 1215

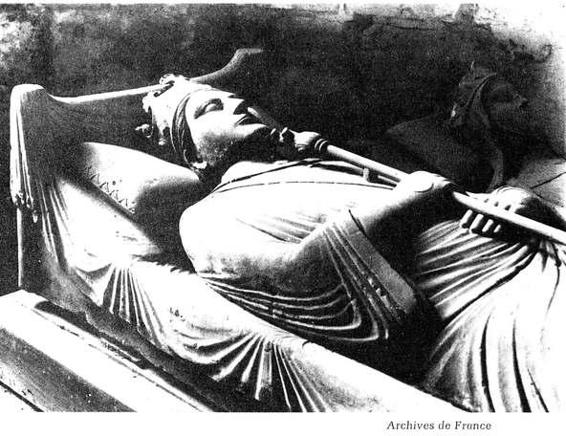

The necropolis of the Plantagenets is in the abbey church at Fontevrault. Above, the tomb effigy of Henry II;

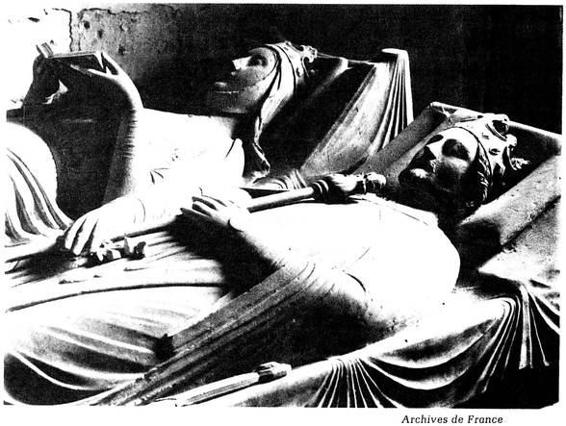

right

, the tomb effigies of Eleanor and Richard. Also buried at Fontevrault Abbey are Joanna and Isabella of Angoulême.

right

, the tomb effigies of Eleanor and Richard. Also buried at Fontevrault Abbey are Joanna and Isabella of Angoulême.

The Abbey of Fontevrault near Tours, founded around 1099 by Robert d’Arbrissel to house a foundation of monks and nuns under the rule of an abbess. Here Eleanor spent the last years of her life.

Betrayals

Exactly how different the decade of the 1160s would be from the previous one the queen was soon to discover. Until the siege of Toulouse, the lucky years had shimmered and slid together, the future appeared so full of promise that the Plantagenets seemed touched by magic or the hand of a benign God. But Christmas of 1159 at Falaise cannot have been a happy one for Eleanor. For the past month, snow and biting winds had swept the Norman countryside, the December sky was colored like iron, and within the cheerless castle where William the Conqueror had been born, the atmosphere was overcast by failure. Henry was not a man to suffer patiently a wife’s sarcasms or recriminations, but on the other hand, neither was Eleanor a person to dissemble her feelings about a war so closely bound up with her own personal ambitions. Like Becket, she could see that Louis, bumbler though he might be, had been successful in confounding the king. Accustomed as she had grown to thinking of Louis as a fool and Henry as the clever one, it must have been unsettling to discover that perhaps her images of both men had been distorted. Henry’s failure at Toulouse seemed enormous to Eleanor, and although there was no open quarreling, the signs of coolness between them were apparent.

Usually, Christmas courts brought on a fierce lust in Henry, but this Christmas, unlike others, Eleanor did not conceive. Perhaps after six years of almost continuous pregnancy she was relieved to take a rest. Henry, a person who did not dwell for very long on either success or failure, had already appeared to have forgotten Toulouse, and now he grew adamant in pressing Eleanor to return to England. She had been absent from the kingdom for a year—he had been away for over two—and while his trust in Richard of Luci and Robert of Leicester remained intact, this was too long a period to leave England unattended by either himself or Eleanor. Perhaps more crucial, however, was his imperative need for money.

Before the Christmas holiday ended, Eleanor left Falaise, and on December 29, despite the bad weather, she boarded the royal yacht

Esnecca

with young Henry and Matilda and crossed the Channel. Her movements during the next few months are reminiscent of Henry’s when the chroniclers declared that he appeared to fly from city to city throughout his domains. At Westminster and Winchester, Eleanor arranged for coin to be loaded on carts and packhorses. Whether following Henry’s instructions or by her own authority, she escorted the treasury collection to Southampton, where it was loaded on the

Esnecca,

but instead of riding back to London, she accompanied the precious cargo to Barfleur, saw it safely unloaded, and then returned immediately to Southampton.

Esnecca

with young Henry and Matilda and crossed the Channel. Her movements during the next few months are reminiscent of Henry’s when the chroniclers declared that he appeared to fly from city to city throughout his domains. At Westminster and Winchester, Eleanor arranged for coin to be loaded on carts and packhorses. Whether following Henry’s instructions or by her own authority, she escorted the treasury collection to Southampton, where it was loaded on the

Esnecca,

but instead of riding back to London, she accompanied the precious cargo to Barfleur, saw it safely unloaded, and then returned immediately to Southampton.

That unfortunate business at Toulouse began to recede from her thoughts as she plunged at once into her administrative duties. To judge from the pipe rolls, she led a peripatetic life, journeying from London to Middlesex to Southampton to Berkshire, from Surrey to Cambridge to Winchester to Dorsetshire, and everywhere she could see signs of growing prosperity. At the same time the records show that, no matter how slovenly a way of life Henry may have accepted, the Eagle believed in living well. During that winter of 1160, one of intense severity, she made numerous improvements in her quarters at Winchester; she ordered vast quantities of wine from Bordeaux, as well as incense, oil for her lamps, and toys for her three boys, now aged five, two and a half, and eighteen months. “For the repair of the Chapel and of the houses and of the walls and of the garden of the Queen ... and for the transport of the Queen’s robe and of her wine and of her Incense, and of the Chests of her Chapel, and for the boys’ shields ... and for the Queen’s chamber and chimney and cellar. 22£. 13s. 2d.” In Hampshire alone she signed thirteen writs authorizing payment to herself of £226, as well as £56 for the expenses of her eldest son, and in London she spent two silver marks on gold to gild the royal cups. By contemporary standards, she was living lavishly, even for a queen.

During this period, her life as regent of England was one in which her husband played little real part. Essentially a person of independent temperament, she functioned most happily when left to her own devices. Although couriers bearing instructions from the king constantly traversed the Channel, the responsibility for carrying out those orders devolved entirely upon herself. Perhaps it was her obsessive need for meaningful work that made her an ideal partner for Henry.

She was thirty-eight years old, no longer the rather frivolous girl who, in the Ile-de-France, had been more concerned with banquets and clothes than attending meetings of the curia. By now, however, she had proved herself an efficient executive, a wife of unswerving loyalty who would dedicate herself to implementing policies that her brilliant young husband had devised. The day had not yet arrived when she would be less willing to play the role of workhorse who unquestioningly carried out policies in whose making she had had no voice.

Other books

The Legend of Deadman's Mine by Joan Lowery Nixon

Third to Die by Carys Jones

The Strawberry Sisters by Candy Harper

The Venice Conspiracy by Sam Christer

Poltergeeks by Sean Cummings

Laying the Ghost by Judy Astley

Down to the Sea by William R. Forstchen

Summer Apart by Amy Sparling