Elizabeth the Queen (15 page)

Read Elizabeth the Queen Online

Authors: Sally Bedell Smith

Still seated in King Edward’s Chair, nearly engulfed by her ponderous golden robes and holding a jeweled scepter upright in each hand, she looked with “intense expectancy” as the archbishop blessed the enormous St. Edward’s Crown of solid gold, set with 444 semiprecious stones. He held it aloft, then placed it firmly on her head, which momentarily dropped before rising again. Simultaneously, the scarlet and ermine robed peers in one section of the Abbey, and the bejeweled peeresses in another, also identically dressed in red velvet and fur-trimmed robes, crowned themselves with their gold, velvet, and ermine coronets. The congregation shouted “God Save the Queen,” and cannons boomed in Hyde Park and at the Tower of London. As the archbishop intoned, “God crown you with a crown of glory and righteousness,” Elizabeth II could literally feel the weight of duty—between her vestments, crown, and scepters, more than forty-five pounds’ worth—on her petite frame.

Accompanied by the archbishop and Earl Marshal, the Queen held the scepters while ascending the platform to sit on her throne and receive the homage of her “princes and peers.” The first was the archbishop, followed by the Duke of Edinburgh, who approached the throne bareheaded in his long red robe, mounted the five steps, and knelt before his wife, placing his hands between hers and saying, “I, Philip, do become your liege man of life and limb, and of earthly worship; and faith and truth I will bear unto you, to live and die, against all manner of folks. So help me God.” When he stood up, he touched her crown and kissed her left cheek, prompting her to quickly adjust the crown as he walked backward and gave his wife a neck bow.

In the royal gallery, tiny Prince Charles, wearing a white satin shirt and dark shorts, arrived through a rear entrance and sat between the Queen Mother and Princess Margaret to witness his mother’s anointing, investiture with regalia, crowning, and homage paid by his father. “Look, it’s Mummy!” he said to his grandmother, and the Queen flashed a faint smile. The four-and-a-half-year-old heir to the throne watched wide-eyed, variously excited and puzzled, while the Queen Mother leaned down to whisper explanations.

The woman who only sixteen years earlier was at the center of the same ceremony smiled throughout, but Beaton also caught in the Queen Mother’s expression “sadness combined with pride.” “She used to say it was like a priesthood, being a monarch,” said Frances Campbell-Preston. “I imagine seeing your daughter go into the anointing must be unusual.” Princess Margaret had a slightly glazed look, and by one account, during the Queen’s investiture “never once did she lower her gaze from her sister’s calm face.” But at the end of the service, she wept. “Oh ma’am you look so sad,” Anne Glenconner said to the princess with the red-rimmed eyes. “I’ve lost my father, and I’ve lost my sister,” Margaret replied. “She will be so busy. Our lives will change.”

The lengthy ceremony ended after a parade of noblemen paid homage, and the congregation celebrated Holy Communion, as the Queen knelt to take the wine and bread “as a simple communicant.” Elizabeth II and her maids of honor took a short break by retiring into the Chapel of St. Edward the Confessor, where she shed her golden vestments, put on her jewelry, and was fitted with a new robe of ermine-bordered purple velvet, lined in white silk and embroidered with a gold crown and E.R. She also exchanged the St. Edward’s Crown, which is worn only once for the coronation, for the somewhat lighter—at three pounds—Imperial State Crown that she would use for the State Opening of Parliament and other major state occasions. This celebrated crown contains some of the most extraordinary gems in the world—the Black Prince’s Ruby, which Henry V wore at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415, the Stuart Sapphire, and the Cullinan II diamond weighing over 317 carats. Before leaving the chapel, the archbishop produced a flask of brandy from beneath his gold and green cope. He passed it around to the Queen and her maids so they could each have a sip as a pick-me-up before the processional.

Carrying the two-and-a-half-pound orb and two-pound scepter, with her maids holding the eighteen-foot train of her robe, the newly crowned Queen walked through the nave of the Abbey to the annex, where she and her attendants had a luncheon of Coronation Chicken—cold chicken pieces in curried mayonnaise with chunks of apricot. Afterward Elizabeth II and Philip settled into the Gold State Coach for two hours in a seven-mile progress through London, this time in the pouring rain.

Back at the Palace, the Queen had a chilled nose and hands from the drafty carriage. But she was ebullient as she relaxed with her maids in the Green Drawing Room. “We were all running down the corridor, and we all sat on a sofa together,” recalled Anne Glenconner. “The Queen said, ‘Oh that was marvelous. Nothing went wrong!’ We were all laughing.” Elizabeth II took off her crown, which Prince Charles put on his head before toppling over, while Princess Anne scampered around giggling underneath her mother’s train. The Queen Mother managed to subdue their wild excitement. She “anchored them in her arms,” Beaton wrote, “put her head down to kiss Prince Charles’s hair.”

It was a day of jubilation not only over the coronation’s success, but because that morning had brought the news that Edmund Hillary of New Zealand and his Tibetan Sherpa, Tenzing Norgay, members of a British mountain climbing team, had been the first to reach the summit of Mount Everest. The “Elizabethan explorers” toasted the Queen with brandy and flew her standard atop the highest mountain in the world, five and a half miles above sea level.

As Earl Warren reported to President Dwight Eisenhower, “the Coronation has unified the nation to a remarkable degree.” An astonishing number of people saw the ceremony on television. In Britain an estimated 27 million out of a population of 36 million watched the live broadcast, and the number of people owning television sets doubled. Future prime minister John Major, then ten years old, fondly recalled seeing the ceremony on his first television, as did Paul McCartney. “It was a thrilling time,” McCartney said. “I grew up with the Queen, thinking she was a babe. She was beautiful and glamorous.” About one third of Americans—some 55 million out of a total population of 160 million—also tuned in, either on the day when they saw only photographs accompanied by a radio feed, or the next day for the full broadcast.

One notably alert viewer in Paris was former King Edward VIII, who had abdicated before he was crowned (an important distinction: as one of the Queen’s friends put it, “he was never anointed, so he never really became king”) and had last attended a coronation in 1911 when he was the sixteen-year-old Prince of Wales and his father was crowned King George V. Now dressed in a stylish double-breasted gray pinstripe suit, the Duke of Windsor watched at the home of Margaret Biddle, a wealthy American who had a “television lunch” for one hundred friends. She positioned three television sets in one room filled with rows of gilt chairs, and the duke sat in the middle of the front row, where he observed the entire telecast “without a sign of envy or chagrin.” At the conclusion of the coronation, he stretched his arms in the air, lit a cigarette, and said coolly, “It was a very impressive ceremony. It’s a very moving ceremony and perhaps more moving because she is a woman.”

“She would especially miss the weekly

audiences which she has found

so instructive and, if one can say so

of state matters, so entertaining.”

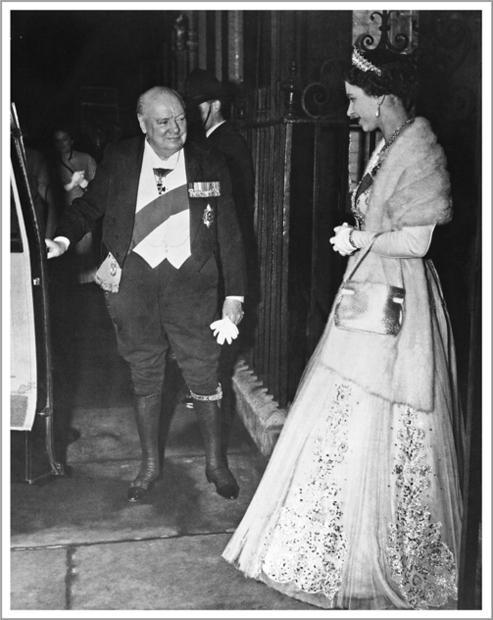

Winston Churchill saying goodbye to Elizabeth II after his farewell dinner on stepping down as prime minister, April 1955.

Associated Press

FIVE

Affairs of State

Affairs of State

A

UREOLE, THE SPIRITED THREE-YEAR-OLD CHESTNUT COLT THAT HAD

been the Queen’s preoccupation in the hours before her crowning, was one of the favorites in the Coronation Derby Day on Saturday, June 6, 1953, the 174th running of the Derby Stakes at Epsom Downs. His sire was Hyperion and his dam Angelola, but his name derived from his grand-sire, the stallion Donatello, named for the Italian Renaissance artist who carved bold halos around the heads of his angelic sculptures.

The Queen relishes choosing names for her foals. With her aptitude at crossword puzzles and parlor games such as charades, she is imaginative and quick to make combinations—the filly Angelola, for example, by Donatello out of the mare Feola, and Lost Marbles out of Amnesia by Lord Elgin. “She would pull on all sorts of knowledge, including old Scottish names,” recalled Jean, the Countess of Carnarvon, whose husband, Henry Porchester—later the Earl of Carnarvon, but known to the Queen as “Porchey”—was Elizabeth II’s racing manager for more than three decades.

The Queen was driven down the Epsom Downs track with her husband in the open rear seat of a Daimler to the cheers of a half million spectators, a record for the course. From the royal box she peered through binoculars as her racing colors (purple body with gold braid, scarlet sleeves, and gold-fringed black velvet cap) flashed along the mile-and-a-half course with twenty-six other galloping thoroughbreds. Aureole held second place, but couldn’t catch Pinza, the winner by four lengths. In her sunglasses and cloche hat, the Queen smiled and waved despite her disappointment. The victorious jockey, forty-nine-year-old Sir Gordon Richards, had received his knighthood (the first ever for a jockey) from the Queen only days earlier. After being invited to meet the Queen, he said she was a “marvelous sport” and “seemed to be just as delighted as I was with the result of the race.”

Also in the royal box was Winston Churchill, the Queen’s most ardent booster throughout the coronation festivities. In the sixteen months—to the day—since she took the throne, she had developed a close and unique bond with Britain’s most formidable statesman. His fondness for both of her parents, along with the shaping experience of World War II, gave them a reservoir of memories and a common perspective, despite their five-decade age difference. She appreciated his wisdom, experience, and eloquence, and looked to him for guidance on how she should conduct herself as monarch.

Churchill was also great company, not least because he shared his monarch’s love of breeding and racing, a passion that came to him late in life. For his Tuesday evening meetings with the Queen, he always arrived at the Bow Room in a frock coat and top hat. The rules of the prime minister’s audience called for complete discretion, so few details of the discussions emerged. Years later when Elizabeth II was asked whose audiences she most enjoyed, she replied, “Winston of course, because it was always such fun.” Churchill’s reply to a query about their most frequent topic of discussion was “Oh, racing,” and his daughter Mary Soames concurred that “they spent a lot of the audience talking about horses.”

Palace courtiers escorted the prime minister to the audiences, waited in the room next door, and afterward enjoyed whisky and soda with him while chatting for a half hour or so. “I could not hear what they talked about,” Tommy Lascelles recorded in his diary, “but it was, more often than not, punctuated by peals of laughter, and Winston generally came out wiping his eyes. ‘She’s

en grande beauté ce soir

,’ he said one evening in his schoolboy French.”

The relationship between the Queen and Churchill prompted comparisons with Queen Victoria, who took the throne at age eighteen, and fifty-eight-year-old William Lamb, Viscount Melbourne, her first prime minister. Melbourne’s manner, wrote Lytton Strachey, “mingled, with perfect facility, the watchfulness and the respect of a statesman and a courtier with the tender solicitude of a parent. He was at once reverential and affectionate, at once the servant and the guide.” Yet when asked directly by former courtier Richard Molyneux early in her reign whether Churchill treated her as Melbourne treated Victoria, Elizabeth II said, “Not a bit of it. I find him very obstinate.”

Nor was she shy about catching out her prime minister when he hadn’t adequately prepared, as happened when Churchill failed to read an important cable from the British ambassador in Iraq. “What did you think about that most interesting telegram from Baghdad?” the Queen asked him that Tuesday. He sheepishly admitted he hadn’t seen it, and returned to 10 Downing Street “in a frightful fury.” When he read the cable, he realized that it was indeed significant.