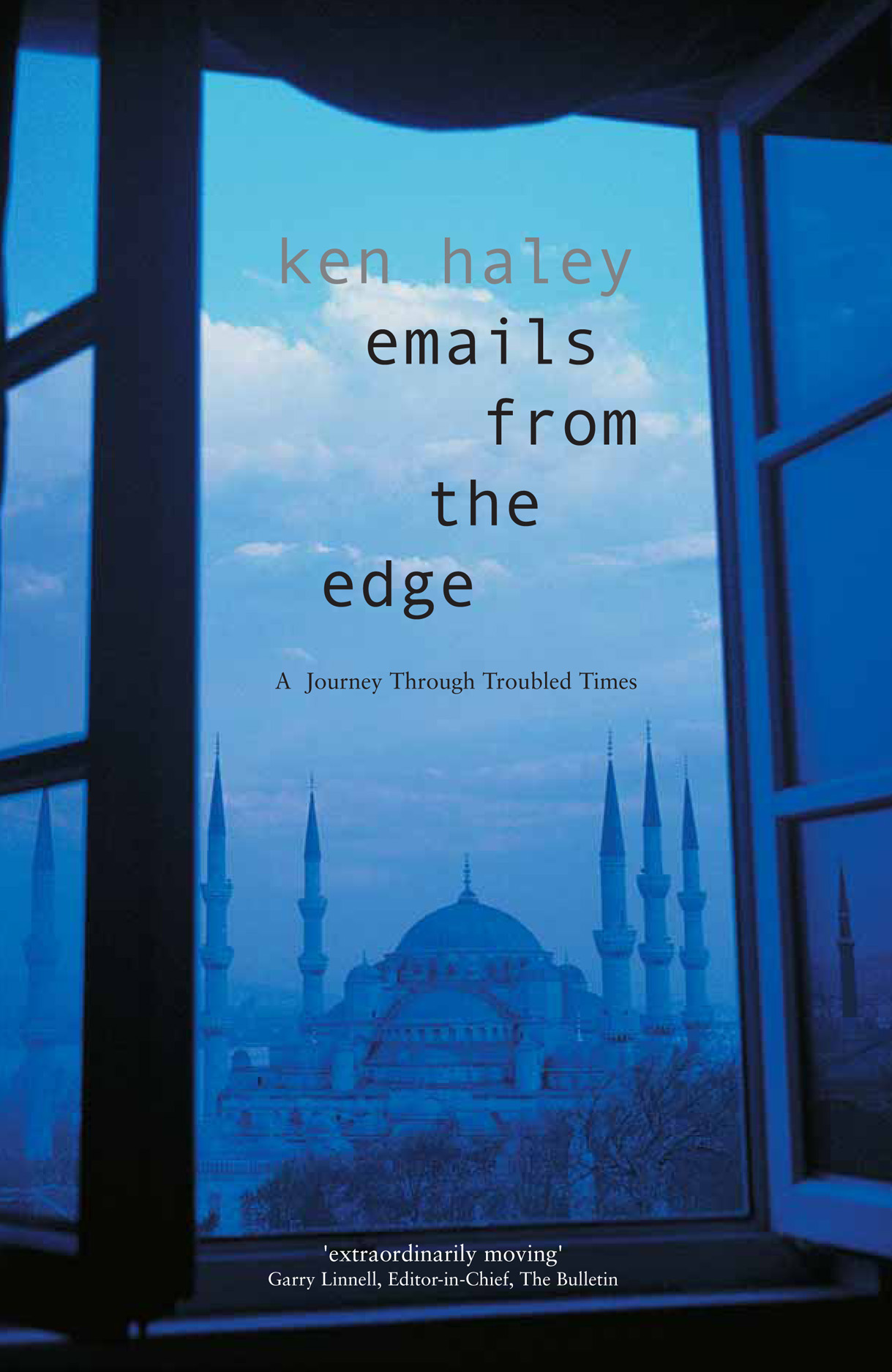

Emails from the Edge

Read Emails from the Edge Online

Authors: Ken Haley

ken  haley

emails

from

the

edge

A Journey Through Troubled Times

emails

from

the

edge

A Journey Through Troubled Times

ken  haley

emails

from

the

edge

A Journey Through Troubled Times

emails

from

the

edge

A Journey Through Troubled Times

EMAILS FROM THE EDGE

First Published 2006 by

Transit Lounge Publishing

95 Stephen Street, Yarraville, Australia 3013

www.transitlounge.com.au

[email protected]

This e-book edition 2011

© Ken Haley 2006

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher.

The copyright holders for

Balkan Ghosts

by Robert D. Kaplan (Vintage Books, New York),

The Book of Laughter and Forgetting

by Milan Kundera (Author),

Waiting for Allah

by Christina Lamb (DGA Ltd),

Journey into Cyprus

by Colin Thubron (Random House Group, London), and

Black Lamb and Grey Falcon

by Rebecca West (Sterling Lord Literistic Inc.) and

A Streetcar Named Desire

by Tennessee Williams (University of the South) have graciously agreed to give permission for the author to cite excerpts from the works named.

Every effort has been made to obtain permission for other excerpts reproduced in this publication. In cases where these efforts were unsuccessful, the copyright holders are asked to contact the publisher directly.

Design by Tim McQuiston

Maps by Ian Faulkner

Printed and bound in Australia by Griffin Press

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-publication data

First Published 2006 by

Transit Lounge Publishing

95 Stephen Street, Yarraville, Australia 3013

www.transitlounge.com.au

[email protected]

This e-book edition 2011

© Ken Haley 2006

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher.

The copyright holders for

Balkan Ghosts

by Robert D. Kaplan (Vintage Books, New York),

The Book of Laughter and Forgetting

by Milan Kundera (Author),

Waiting for Allah

by Christina Lamb (DGA Ltd),

Journey into Cyprus

by Colin Thubron (Random House Group, London), and

Black Lamb and Grey Falcon

by Rebecca West (Sterling Lord Literistic Inc.) and

A Streetcar Named Desire

by Tennessee Williams (University of the South) have graciously agreed to give permission for the author to cite excerpts from the works named.

Every effort has been made to obtain permission for other excerpts reproduced in this publication. In cases where these efforts were unsuccessful, the copyright holders are asked to contact the publisher directly.

Design by Tim McQuiston

Maps by Ian Faulkner

Printed and bound in Australia by Griffin Press

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-publication data

Haley, Ken, 1954- .

Emails from the Edge: a journey through troubled times.

Bibliography

ISBN 9781921924071 (e-book)

1. Haley, Ken 1954- . -Travel - Eurasia. 2. Journalists - Australia - Biography. 3. Paraplegics - Australia - Biography. 4. Eurasia - Description and travel. I. Title.

070.92Emails from the Edge: a journey through troubled times.

Bibliography

ISBN 9781921924071 (e-book)

1. Haley, Ken 1954- . -Travel - Eurasia. 2. Journalists - Australia - Biography. 3. Paraplegics - Australia - Biography. 4. Eurasia - Description and travel. I. Title.

For my parents, without whom all this would have

been impossible, and I even more so

.

been impossible, and I even more so

.

CONTENTS

Preface

1.   Lower, Faster, Further

2.   Where I'm Coming From

3.   Straws in the Desert Wind

4.   There's No Going Back

5.   Heretics and H-Bombs

6.   One Steppe at a Time

7.   Turkmania

8.   Night Vision

9.   Whistling in the Dark

10. Caucasian Features

11. September 11, 2001

12. The Muslim Heartlands

13. Falling from the Edge

14. Rejected for Heaven

15. The Growing Gulf

16. You Are Welcome in Jordan

17. Knock, Knock, Knocking on Europe's Door

18. The Glory That Is Greece

19. The Curse of the Balkans

20. Waltzing by the Danube

21. A Bad Case of Muscovitis

22. The Usual Delinquencies

23. Here Beginneth the Afterlife

24. Finnish Line

Maps

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Preface

1.   Lower, Faster, Further

2.   Where I'm Coming From

3.   Straws in the Desert Wind

4.   There's No Going Back

5.   Heretics and H-Bombs

6.   One Steppe at a Time

7.   Turkmania

8.   Night Vision

9.   Whistling in the Dark

10. Caucasian Features

11. September 11, 2001

12. The Muslim Heartlands

13. Falling from the Edge

14. Rejected for Heaven

15. The Growing Gulf

16. You Are Welcome in Jordan

17. Knock, Knock, Knocking on Europe's Door

18. The Glory That Is Greece

19. The Curse of the Balkans

20. Waltzing by the Danube

21. A Bad Case of Muscovitis

22. The Usual Delinquencies

23. Here Beginneth the Afterlife

24. Finnish Line

Maps

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

PREFACE

The title of this book occurred to me upon awakening one mid-April day in 2001, shortly before I set out on the transcontinental journey it describes.

It was in my mind that if I were to send home a collection of newspaper articles from the countries en route they might cover such a range of themes that, as I would be using Internet cafés to deliver them, this would constitute a fairly new use of email which might somehowâprecious thoughtâmarry the staccato rhythms of that medium with the more sustained notes contained in news features.

So it was no coincidence that my irregular series of travel articles published in the Melbourne

Age

over the next two years was christened âEmails from the Edge'.

In 2003, when it became clear that this book would be written not in Australia but in far-off Namibia, and that posting a hard-copy manuscript would be problematic, the title acquired a secondary, quite eerie, significance, because now the book itself would be sent to my long-suffering publishers in the form of emails from the edge of Africa.

At about the same time, when discussing with the publisher what form this memoir should take, I could see that to tell only of my outward journey and not of the inner one would be to tell half a story, or a kind of lie.

People, like continents, have edges. To cross one's own is a different voyage, undertaken with no obvious return ticket. But there are many roads back to a whole life.

At the time of going to print, self-exploration was free of charge and there was still no departure tax on flights of the imagination.

The title of this book occurred to me upon awakening one mid-April day in 2001, shortly before I set out on the transcontinental journey it describes.

It was in my mind that if I were to send home a collection of newspaper articles from the countries en route they might cover such a range of themes that, as I would be using Internet cafés to deliver them, this would constitute a fairly new use of email which might somehowâprecious thoughtâmarry the staccato rhythms of that medium with the more sustained notes contained in news features.

So it was no coincidence that my irregular series of travel articles published in the Melbourne

Age

over the next two years was christened âEmails from the Edge'.

In 2003, when it became clear that this book would be written not in Australia but in far-off Namibia, and that posting a hard-copy manuscript would be problematic, the title acquired a secondary, quite eerie, significance, because now the book itself would be sent to my long-suffering publishers in the form of emails from the edge of Africa.

At about the same time, when discussing with the publisher what form this memoir should take, I could see that to tell only of my outward journey and not of the inner one would be to tell half a story, or a kind of lie.

People, like continents, have edges. To cross one's own is a different voyage, undertaken with no obvious return ticket. But there are many roads back to a whole life.

At the time of going to print, self-exploration was free of charge and there was still no departure tax on flights of the imagination.

Chapter 1

LOWER, FASTER, FURTHER

14TH-CENTURY PERSIAN SUFI POET, FROM ANTHOLOGY

D

IVAN OF

H

AFEZ

CHRISTMAS 2001

Christmas is hardly the word for it, but unmistakable signs of the season were everywhere: there was no room at inn after inn, and tinselled trees sprouted in hotel foyers, welcoming Westerners to that part of the world where it all began.

They welcomed me to Manama, downtown Bahrain, an urban oasis wedged between the Arabian desert and opal-blue Gulf. At the commercial heart of this oasis, the Hotel Aradous beckoned me in from the unremitting heat of the street to the cool relief of its high-ceilinged interior.

This could have been a European grand hotel, from its glittering chandelier and room-key boxes at reception right down to the potted palms. But a glance outside would have cured anyone of such a misconception. From there emanated all the sounds and smells, the tingling, jangling and spicy aromas, that make up an Eastern bazaar.

On either side of the hotel's entrance were two shops: one a jeweller's, the other a moneychanger's, testament to the reign of commerce in this realm. In the alley that ran alongside the Aradous, I passed a tarpaulin-covered teashop, an airy refuge from the ceaseless hubbub of traders. A few metres further down the alley, I came upon a security door where, having made prior arrangements for entering at ground level and avoiding staircases, I found an eager hotel porter waiting.

He unlocked the door, re-locked it at once, and led me through a warren of corridors that eventually brought me back to the foyer. Here I found myself asking yet again those questions that coming from any other guest would have sounded absurd: not only, âDo you have a room for six nights?' but also, âCould I have a look first to see whether I can get into the bathroom?'

All this arranged without too much fuss, we finally broached the question of the tariffâas important to me as to any budget traveller, and I still classed myself as one because, although this was no ordinary journey, I remained averse to paying gold-brick prices for base-metal accommodation. After Central Asia, where expenses could be kept within tolerable bounds, the Gulf had come as a rude shock to the wallet. In this region my usual ceiling, US$40 a night, was the basement.

There's no such thing as a cheap room in Bahrain's tourist quarter but the Aradous seemed the best option. So, as I waited for the reception staff to deal with other guests first, my mind wound back eleven years to 1990, when I had worked as a sub-editor on the national newspaperâand, anticipating the moment the duty manager's roving eye fell on me, I took the opportunity to beg a favour.

âMay I use your phone for a local call, please?'

âCertainly,' he replied, idly pushing the device across the counter.

I picked up the receiver, checked my newly bought copy of the

Gulf Daily News

, and dialled.

âCould you put me through to the editor?' I asked, having noted in the paper that the deputy editor when I worked there had since been promoted. His familiar English Midlands accent came on the line.

âKen Haley here. I'm back in Bahrain, for the first time since I was working here.'

âOh, Ken,' he sounded slightly lost for words, âhow have you been?'

âVery well. Time heals, as they say.' A pause. âI wouldn't mind seeing you ⦠while I'm here.'

âThat would be fantastic. Why don't you ring tomorrow? We'd be glad to see you. If you're staying in town, you could catch a bus out to the office.'

âYes, well ⦠' (the moment of revelation could not be deferred, as I knew the office layout well enough and the editorial offices were literally up stairs on the first floor), âit would be fine to meet at the office but I have something to tell you if you have a moment to spare.'

ââ¦Yes?'

âYou needn't worry about this,' I began, a past master at imparting this fact to old acquaintances, âbut a few years ago I had a spot of bad luck and I should tell you that these days I'm in a wheelchair.'

Silence. I could have counted off the seconds, but took up the conversational slack after a handful had elapsed. âThere's really no need to worry, I've had a successful career since those days, and the fact I've just travelled all across Central Asia and Iran to get here will tell you that. So the office is out of the question, but somewhere in town perhaps?'

It takes more than a telephone to screen out the smell of fear. I could tell from this brief encounter that a meeting which should have provided resolution, a neat rounding off, to a very messy episode from a difficult time was now not going to take place. A chill dread had made that meetingâso imminent a minute agoâdisappear. Even though to all the world I was the disabled one, all the pain would be weighing down his side of the ledger. What I looked to as closure would for him have been an openingâon to the worst of times.

So the next night I rang the editor's office back hour after hour after hour only to be serially fobbed off. In the end I tried to ignore the clenching of my chest, pocketed the indignity and steeled myself to look on it as something other than blameworthy, as nothing more or less than Fate.

LOWER, FASTER, FURTHER

In the path of verse, behold the travelling of place and of time!

The child of one night, the path of one year goeth

.

A COUPLET BY HAFEZ (KHAJEH SHAMSEDDIN MOHAMMAD HAFEZ SHIRAZI),The child of one night, the path of one year goeth

.

14TH-CENTURY PERSIAN SUFI POET, FROM ANTHOLOGY

D

IVAN OF

H

AFEZ

CHRISTMAS 2001

Christmas is hardly the word for it, but unmistakable signs of the season were everywhere: there was no room at inn after inn, and tinselled trees sprouted in hotel foyers, welcoming Westerners to that part of the world where it all began.

They welcomed me to Manama, downtown Bahrain, an urban oasis wedged between the Arabian desert and opal-blue Gulf. At the commercial heart of this oasis, the Hotel Aradous beckoned me in from the unremitting heat of the street to the cool relief of its high-ceilinged interior.

This could have been a European grand hotel, from its glittering chandelier and room-key boxes at reception right down to the potted palms. But a glance outside would have cured anyone of such a misconception. From there emanated all the sounds and smells, the tingling, jangling and spicy aromas, that make up an Eastern bazaar.

On either side of the hotel's entrance were two shops: one a jeweller's, the other a moneychanger's, testament to the reign of commerce in this realm. In the alley that ran alongside the Aradous, I passed a tarpaulin-covered teashop, an airy refuge from the ceaseless hubbub of traders. A few metres further down the alley, I came upon a security door where, having made prior arrangements for entering at ground level and avoiding staircases, I found an eager hotel porter waiting.

He unlocked the door, re-locked it at once, and led me through a warren of corridors that eventually brought me back to the foyer. Here I found myself asking yet again those questions that coming from any other guest would have sounded absurd: not only, âDo you have a room for six nights?' but also, âCould I have a look first to see whether I can get into the bathroom?'

All this arranged without too much fuss, we finally broached the question of the tariffâas important to me as to any budget traveller, and I still classed myself as one because, although this was no ordinary journey, I remained averse to paying gold-brick prices for base-metal accommodation. After Central Asia, where expenses could be kept within tolerable bounds, the Gulf had come as a rude shock to the wallet. In this region my usual ceiling, US$40 a night, was the basement.

There's no such thing as a cheap room in Bahrain's tourist quarter but the Aradous seemed the best option. So, as I waited for the reception staff to deal with other guests first, my mind wound back eleven years to 1990, when I had worked as a sub-editor on the national newspaperâand, anticipating the moment the duty manager's roving eye fell on me, I took the opportunity to beg a favour.

âMay I use your phone for a local call, please?'

âCertainly,' he replied, idly pushing the device across the counter.

I picked up the receiver, checked my newly bought copy of the

Gulf Daily News

, and dialled.

âCould you put me through to the editor?' I asked, having noted in the paper that the deputy editor when I worked there had since been promoted. His familiar English Midlands accent came on the line.

âKen Haley here. I'm back in Bahrain, for the first time since I was working here.'

âOh, Ken,' he sounded slightly lost for words, âhow have you been?'

âVery well. Time heals, as they say.' A pause. âI wouldn't mind seeing you ⦠while I'm here.'

âThat would be fantastic. Why don't you ring tomorrow? We'd be glad to see you. If you're staying in town, you could catch a bus out to the office.'

âYes, well ⦠' (the moment of revelation could not be deferred, as I knew the office layout well enough and the editorial offices were literally up stairs on the first floor), âit would be fine to meet at the office but I have something to tell you if you have a moment to spare.'

ââ¦Yes?'

âYou needn't worry about this,' I began, a past master at imparting this fact to old acquaintances, âbut a few years ago I had a spot of bad luck and I should tell you that these days I'm in a wheelchair.'

Silence. I could have counted off the seconds, but took up the conversational slack after a handful had elapsed. âThere's really no need to worry, I've had a successful career since those days, and the fact I've just travelled all across Central Asia and Iran to get here will tell you that. So the office is out of the question, but somewhere in town perhaps?'

It takes more than a telephone to screen out the smell of fear. I could tell from this brief encounter that a meeting which should have provided resolution, a neat rounding off, to a very messy episode from a difficult time was now not going to take place. A chill dread had made that meetingâso imminent a minute agoâdisappear. Even though to all the world I was the disabled one, all the pain would be weighing down his side of the ledger. What I looked to as closure would for him have been an openingâon to the worst of times.

So the next night I rang the editor's office back hour after hour after hour only to be serially fobbed off. In the end I tried to ignore the clenching of my chest, pocketed the indignity and steeled myself to look on it as something other than blameworthy, as nothing more or less than Fate.

Chapter 2

WHERE I'M COMING FROM

T

HE

V

ALLEYS OF THE

A

SSASSINS

I cannot plead anything particularly out of the ordinary in my childhood, except the child. The middle son of three, I was born into a conventional lower-middle-class family and raised on what lay near the edge of Melbourne's sprawling suburbia in the 1960s and is now a middle suburb. As it happens, my younger brother and his wife now live in that same, formerly weatherboard, house. I received a state-school education and probably had a more religious upbringing than most in secular Australia, owing to a devout maternal grandmother. My politics, though, I inherited from Dad, a traditional Labor voter.

In Australia âtall poppies' are there to be cut down. Mum was, as she remains, an engaging mixture of egalitarianism and keeping up proper social standards. A certain woman down the street might be âcommon' but a more heinous offence was to be âa snob'. Somewhere in the great comfortable middle ground: that was where you belonged.

Except that I didn't. My rebellious spirit, combined with artistic inclinations, meant that when my grandmother bought me a piano for my sixth birthday I kicked against the discipline of strict morning practice hours but would then playâloudly and discordantly, it must be saidâwell into the evening.

Beyond boundaries, I became myself, felt free, grew wild.

While I was a loner, the gift of the gab (my part-Irish heritage?) made me quite a persuasive character, and, like most other teenagers, I craved the approval of my peers. But somehow the âloner' and the observer within me proved stronger than the participant. As they shaped my personality I discovered that some of life's richest pleasuresâthough not happiness, damn itâare reserved for those of us who do our own thinking and imagining, who ask âWhy?' and âWhat if?' more than is really good for us.

You would have described me as inquisitive rather than acquisitiveâ and this is a curse as much as a blessing. Somehow I survived high school, by talking my way out of trouble as often as I talked myself into it, and by concentrating on flight rather than fight (being on the move is nothing new to me, you see).

Cultivating individuality, refusing to follow the pack, served me well when I became a journalist, but there was a price to pay. No amount of planing off the social edges of your personality is going to make it anything but deformed. âKnow thyself,' said the Greeks. âBe yourself,' say the moderns. They're both right, of course, but you can't really achieve the second until you've mastered the firstâwhich takes decades, guaranteeing a bumpy ride along the way.

My curiosity got me into this life of journalism alternating with travel: it is the personal denominator common to both. The first news event that swam into my view was the flight of Sputnik. A half-formed image resides somewhere in my consciousness of being held aloft in the front yard, at the age of three, and seeing a pinpoint of white light streak across the sky.

The urge to break away, to disappear, kicked in quite young. I remember when, aged ten, I left my grandmother during a day's outing in the inner suburb of Richmond, to test a theory that if I went in a certain direction I could walk all the way home. That evening I knocked nonchalantly on our front door in South Oakleigh, 15 kilometres away, to be greeted with a welcome that was memorable enough but somewhat deficient in the congratulations I'd been counting on.

At 20 I went walkabout: up-country to the MurrayâDarling basin, taking literally a great aunt's idle invitation to visit one day. âWork' hadn't figured in my vision of what would follow but board was not going to be free so I adapted fast. In my ignorance, I had arrived at just the right season to pick up shifts as an orange packer in Coomealla, and when that ended I hitchhiked to Adelaide where I became a part-time piano player in a city pub. I even enrolled in an Arts course at Flinders University and stayed five days (and I'm glad of that because university experience always adds lustre to the résumé). But the sad truth was that my money reserves were getting perilously low so the dream of becoming a journalist and beginning a life's work could be put off no longer.

It was a profession that I, with my love of language and utter fearlessness when it came to asking dumb questions, took to like a duck to H

2

0. One of the great attractions of being a reporter is that every day brings variety of experience and fresh ideas.

For my restless spirit, new experiences proved a satisfying substitute for new sights, although my wanderlust never slept for long. On weekends I would get into my battered old Torana and hare around the country. When reporting politics from Canberra for the Melbourne

Age

, I clocked up thousands of kilometres around New South Wales in my spare time.

A relish for solitude, added to a hunger for new views, meant that I could fairly claim to have âseen' my homeland, Australiaâall six states and both territoriesâlong before I first set foot overseas, on New Year's Eve 1980. That trip took me to Australia's immediate northern neighbourhood: Papua New Guinea, Indonesia, Singapore and Malaysia. In later years, my journeys propelled me progressively farther afield.

Even the experienced traveller makes plenty of mistakes but the natural apprehensions most people feel at being a stranger in the crowd, or far away from home, never afflict me. There is just so much of interest in a fresh destination that until there is a clear and present danger my âfear sensor' is almost always switched off, or at least turned way down low.

Bahrain, the first time round, set my sensor shrieking so alarmingly that it would be many years before I could face the idea of revisiting the scene of my psychic invasion. Like a GI returning to Normandy, I couldn't blot out the thought that something of my self had been left behind thereâsomething irrecoverable yet, for all that, something that kept calling to me across the passage of decades, something embedded in the sands of time.

WHERE I'M COMING FROM

I know in my heart of hearts that it is a most excellent reason to do things merely because one likes the doing of them

.

FREYA STARK.

T

HE

V

ALLEYS OF THE

A

SSASSINS

I cannot plead anything particularly out of the ordinary in my childhood, except the child. The middle son of three, I was born into a conventional lower-middle-class family and raised on what lay near the edge of Melbourne's sprawling suburbia in the 1960s and is now a middle suburb. As it happens, my younger brother and his wife now live in that same, formerly weatherboard, house. I received a state-school education and probably had a more religious upbringing than most in secular Australia, owing to a devout maternal grandmother. My politics, though, I inherited from Dad, a traditional Labor voter.

In Australia âtall poppies' are there to be cut down. Mum was, as she remains, an engaging mixture of egalitarianism and keeping up proper social standards. A certain woman down the street might be âcommon' but a more heinous offence was to be âa snob'. Somewhere in the great comfortable middle ground: that was where you belonged.

Except that I didn't. My rebellious spirit, combined with artistic inclinations, meant that when my grandmother bought me a piano for my sixth birthday I kicked against the discipline of strict morning practice hours but would then playâloudly and discordantly, it must be saidâwell into the evening.

Beyond boundaries, I became myself, felt free, grew wild.

While I was a loner, the gift of the gab (my part-Irish heritage?) made me quite a persuasive character, and, like most other teenagers, I craved the approval of my peers. But somehow the âloner' and the observer within me proved stronger than the participant. As they shaped my personality I discovered that some of life's richest pleasuresâthough not happiness, damn itâare reserved for those of us who do our own thinking and imagining, who ask âWhy?' and âWhat if?' more than is really good for us.

You would have described me as inquisitive rather than acquisitiveâ and this is a curse as much as a blessing. Somehow I survived high school, by talking my way out of trouble as often as I talked myself into it, and by concentrating on flight rather than fight (being on the move is nothing new to me, you see).

Cultivating individuality, refusing to follow the pack, served me well when I became a journalist, but there was a price to pay. No amount of planing off the social edges of your personality is going to make it anything but deformed. âKnow thyself,' said the Greeks. âBe yourself,' say the moderns. They're both right, of course, but you can't really achieve the second until you've mastered the firstâwhich takes decades, guaranteeing a bumpy ride along the way.

My curiosity got me into this life of journalism alternating with travel: it is the personal denominator common to both. The first news event that swam into my view was the flight of Sputnik. A half-formed image resides somewhere in my consciousness of being held aloft in the front yard, at the age of three, and seeing a pinpoint of white light streak across the sky.

The urge to break away, to disappear, kicked in quite young. I remember when, aged ten, I left my grandmother during a day's outing in the inner suburb of Richmond, to test a theory that if I went in a certain direction I could walk all the way home. That evening I knocked nonchalantly on our front door in South Oakleigh, 15 kilometres away, to be greeted with a welcome that was memorable enough but somewhat deficient in the congratulations I'd been counting on.

At 20 I went walkabout: up-country to the MurrayâDarling basin, taking literally a great aunt's idle invitation to visit one day. âWork' hadn't figured in my vision of what would follow but board was not going to be free so I adapted fast. In my ignorance, I had arrived at just the right season to pick up shifts as an orange packer in Coomealla, and when that ended I hitchhiked to Adelaide where I became a part-time piano player in a city pub. I even enrolled in an Arts course at Flinders University and stayed five days (and I'm glad of that because university experience always adds lustre to the résumé). But the sad truth was that my money reserves were getting perilously low so the dream of becoming a journalist and beginning a life's work could be put off no longer.

It was a profession that I, with my love of language and utter fearlessness when it came to asking dumb questions, took to like a duck to H

2

0. One of the great attractions of being a reporter is that every day brings variety of experience and fresh ideas.

For my restless spirit, new experiences proved a satisfying substitute for new sights, although my wanderlust never slept for long. On weekends I would get into my battered old Torana and hare around the country. When reporting politics from Canberra for the Melbourne

Age

, I clocked up thousands of kilometres around New South Wales in my spare time.

A relish for solitude, added to a hunger for new views, meant that I could fairly claim to have âseen' my homeland, Australiaâall six states and both territoriesâlong before I first set foot overseas, on New Year's Eve 1980. That trip took me to Australia's immediate northern neighbourhood: Papua New Guinea, Indonesia, Singapore and Malaysia. In later years, my journeys propelled me progressively farther afield.

Even the experienced traveller makes plenty of mistakes but the natural apprehensions most people feel at being a stranger in the crowd, or far away from home, never afflict me. There is just so much of interest in a fresh destination that until there is a clear and present danger my âfear sensor' is almost always switched off, or at least turned way down low.

Bahrain, the first time round, set my sensor shrieking so alarmingly that it would be many years before I could face the idea of revisiting the scene of my psychic invasion. Like a GI returning to Normandy, I couldn't blot out the thought that something of my self had been left behind thereâsomething irrecoverable yet, for all that, something that kept calling to me across the passage of decades, something embedded in the sands of time.

Other books

The Lanyard by Carter-Thomas, Jake

Recipes for Disaster by Josie Brown

The Desolate Guardians by Matt Dymerski

The Borrowers Afield by Mary Norton

When the Stars Threw Down Their Spears: The Goblin Wars, Book Three by Kersten Hamilton

The Funeral Dress by Susan Gregg Gilmore

The Trenches by Jim Eldridge

The Salisbury Manuscript by Philip Gooden

Four Quarters of Light by Brian Keenan