Embers of War (66 page)

Authors: Fredrik Logevall

Tags: #History, #Military, #Vietnam War, #Political Science, #General, #Asia, #Southeast Asia

The evacuation of Lai Chau was a major blow for the French-Vietnamese antiguerrilla forces operating in the Tai country. It also allowed the Viet Minh to extend their all-weather road from Kunming to the frontier near Phong Tho, down through Lai Chau, and toward Tuan Giao. Even the most skilled army press officer could not cover the fact that the loss of Lai Chau was, in these ways, a significant military defeat. Psychologically too it hurt, for the town was the capital of the Tai tribes and a symbol of French support and strength in the region. Now it was gone. On December 12, regiments of the 316th Division entered the abandoned town.

3

The division’s pace had been relentless, even for an army that had long since proved its ability to traverse wide stretches of difficult country at speed. Troops covered twenty miles by day, usually just off the roads, or up to thirty by night, since under darkness they did not have to worry about concealment from the air. Each man carried his weapon, a week’s supply of rice (usually replenished at depots along the way), a water bottle, a shovel, a mosquito net, and a little salt in a bamboo tube. He marched from dawn to dusk, or vice versa, with a ten-minute rest every hour. The nighttime marches were blissfully cool but physically much more grueling. Upon arrival, groups of soldiers dug a foxhole in which to take shelter and sleep, spreading a piece of nylon on the bottom. Then they washed their feet with salt water. Some men had footwear, while some made do with sandals cut out of tires. Fatigue was constant, and food was sometimes limited to greens and bamboo shoots picked in the jungle.

4

Vietnamese accounts give few hints of the morale problems alluded to by Ho Chi Minh back in September, but surely they existed, among some units at least. The pace was too rapid, the conditions too punishing, the terrain too treacherous, for it to have been otherwise. But neither can it be doubted that the 316th showed extraordinary resilience and cohesiveness, moving so far so fast, nor that its positioning posed a serious danger to the garrison at the south end of the Pavie Piste.

The man given the task of meeting that threat was Colonel Christian Marie Ferdinand de la Croix de Castries, age fifty-one, a tall, debonair, aristocratic cavalryman who became commander at Dien Bien Phu early in the Lai Chau evacuation. De Castries, however, didn’t convey much concern. It was his nature to assume a nonchalant air when confronted with major challenges, and conversely to be overly serious about less important matters. Descended from a long line of high military officers—one marshal, one admiral, and eight generals, one of whom had served with Lafayette in America—de Castries was dashing and courageous, a notorious womanizer, a dilettante with a file full of youthful peccadilloes. If there was a fashionable high-society event in interwar Paris, chances were de Castries was in attendance, each time with a different woman on his arm. A superb horseman, he had won two world riding titles in the 1930s—he was the only person to hold both the high- and broad-jump records. Taken prisoner by the Germans in the Battle of France, he escaped in 1941 and, as a major in the liberation army, led troops in the Italian, French, and German campaigns. In 1946 de Castries went to Indochina, and he returned for a second tour in 1951, sustaining injuries at Vinh Yen. Navarre had known him for years and had been his regimental commander during the victorious dash into Germany in 1944–45; the two cavalrymen got on well. Cogny gave his assent to the appointment, but mostly because he thought de Castries supercilious and vain and wanted him away from his own headquarters in Hanoi.

5

De Castries arrived at Dien Bien Phu on December 8, sporting a glittering shooting stick, a scarlet foulard, and the red

calot

, or peaked overseas cap, of his old cavalry regiment. No shrinking violet he. Jean Gilles, relieved to be leaving, showed him around the camp and introduced him to the officers, some of whom were quick to point out that commando operations outside the valley were already encountering severe problems. The enemy was in close, they told him; they were hemmed in. For de Castries, whose dislike for static, defensive warfare was well-known, who indeed had been selected for the job in part because he, possessing the cavalryman’s gambler mentality, would activate Navarre’s plan for offensive operations, it should have been a sobering message. But he struck an upbeat tone in those early days, even as news filtered in of the terrible fate suffered by the Tai partisans struggling southward from Lai Chau. Probably the officers were exaggerating the difficulties of the mobile operations, he thought. And besides, the enemy would not have heavy weapons at his disposal. Even if by some miracle he got some of them in place on the hillside, the French artillery would soon annihilate them.

6

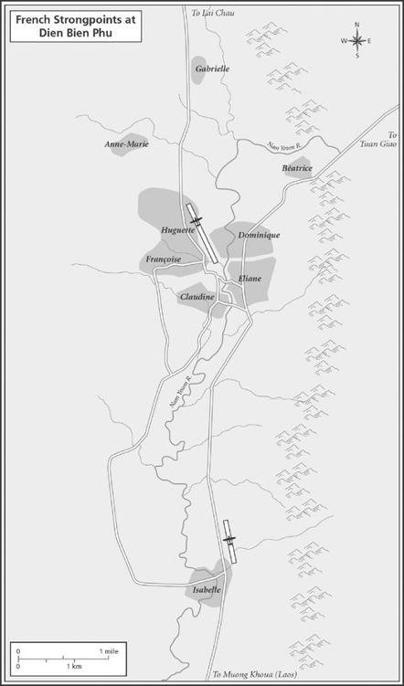

And so, de Castries got to work supervising the construction of strong-points in the valley. Eventually there would be nine of them, all given female names—reputedly those of former de Castries mistresses (though also representing letters of the alphabet). Most of the garrison was packed in defensive positions around the airstrip—Dominique, Huguette, Claudine, and Eliane—while to the west stood the smaller Françoise. On two small hills to the north and northeast, a mile and a half away, there were Gabrielle and Béatrice, each holding a battalion. Beyond Huguette to the northwest, a series of loosely connected points manned by Tai auxiliaries was christened Anne-Marie, while three miles to the south, all by herself, stood Isabelle. Two battalions were given the tasks of supporting the central position with artillery fire and of defending a secondary airstrip. Much effort went into protecting the defensive positions with bunkers, trenches, and barbed-wire entanglements and into the construction of an underground central headquarters and hospital. There would be water filtration plants (amoebic dysentery was endemic), generating stations, maintenance repair shops for tanks, ammunition dumps, and general stores.

The problem was acquiring sufficient building material for this work—some thirty thousand tons, according to the estimate of Major André Sudrat, the engineering commander. Realizing quickly that having even a fraction of that tonnage flown in would be impossible (especially given that food and ammunition would have priority), Sudrat asked for what he considered the bare essentials: three thousand tons of barbed wire. If he expected the resources of the valley to provide a significant substitute for the missing shipments, he was soon disappointed. There was no cement, no sand, no stone, no brick, and curiously enough, almost no wood. The basin was almost completely devoid of trees, while the wooded slopes were trackless. Venturing farther out for timber was a fool’s errand, for there lurked Viet Minh scouts and skirmishers. The chief engineer thus saw no option but to order the demolishing of local peasants’ dwellings to obtain what little wood could be had—thereby, of course, earning their enmity. With the shrubbery going to fuel the garrison’s cooking fires, the valley soon began to resemble a barren moonscape. This in itself did not trouble the French; for them it was standard procedure to open fields of fire and deny cover to the enemy. But it was welcome news to the Viet Minh, whose forward observers, from their positions on the hills, could distinctly see the French coming and going like ants in the valley basin, could observe their routines, could learn their ways. With binoculars, even de Castries and his red scarf could easily be discerned.

7

II

NO DOUBT THE BINOCULARS WERE OUT WHEN A SPECIAL VISITOR

deplaned on Christmas Eve. It was General Navarre, there to celebrate mass with his troops. The garrison was by then a formidable entity, at least in terms of size, each day over the past weeks having brought reinforcements by air: Foreign Legion, Moroccan, and Algerian battalions; colonial artillery batteries with sizable numbers of black African gunners; intelligence and engineer units; doctors and nurses; and even, for the Legion, prostitutes of two

bordels mobiles de campagne

—mobile field bordellos. The number of French Union troops in the valley now totaled 10,910, and the steady stream of Dakotas was also bringing large amounts of weaponry and ammunition. American-supplied Bearcat fighters were in place. Navarre could even view the first platoon of three U.S.-made M-24 “Chaffee” tanks being readied for action. They had been airlifted into the camp in two sections—chassis and turret—and were being reassembled laboriously with a block-and-tackle rig.

8

Word of the general’s arrival soon spread from one strongpoint to the next. He was not a popular man among the officers and men, but he won credit for making this effort to be with his troops for the holiday—which, in the Continental tradition, was celebrated on Christmas Eve. He might be cold and distant, clumsy in his shyness, a mere armchair general, they told one another, but at least he’s here. The visit raised spirits among the battalions and around the spindly, vaguely sinister-looking Christmas tree decorated with whatever colored bits of paper and cotton a group of soldiers and nurses had managed to find. By nightfall the strains of “Stille Nacht, heilige Nacht,” sung by German legionnaires, could be heard rising into the darkness, accompanied by faint mortar shots in the distance. At the officers’ mess of the Legion, meanwhile, there was more singing, and much coarse conversation, as the champagne flowed.

9

GENERAL NAVARRE, LEFT, AT DIEN BIEN PHU ON CHRISTMAS EVE 1953. IN THE DRIVER’S SEAT IS COLONEL DE CASTRIES, COMMANDER OF THE GARRISON.

(photo credit 17.1)

It was, in part, an attempt at escape. You had to force yourself to celebrate the festivities as if the mountains shrouded in darkness and fog were not alive with enemy troops bent on your annihilation. You had to forget that you were surrounded on all sides. “There was a strange atmosphere in the camp,” recalled Howard Simpson, the perspicacious USIA correspondent, who was in the camp one or two days earlier. “The officers remained cocky and determined, but the men, particularly the North Africans, Tai, and some of the Vietnamese, seemed to have been affected by the boredom, the lack of movement, and the threat of what was ‘out there.’ A troubled silence fell over the dark valley after sundown. Nervous gunners occasionally loosed a stream of seemingly slow-moving tracers into the night, jeeps with hooded headlights bumped over the rough roads, and the odiferous open latrines glowed with the phosphorescence of seething maggots.”

10

Navarre picked up on this underlying unease, indeed felt it himself. He was sullen and withdrawn on the visit—even by his usual standards. He made no uplifting speech, no effort to put heart into his men. “The military conditions for victory have been brought together,” he assured both de Castries in an early closed-door meeting and a group of officers later on. But his words lacked conviction, for he also expressed worry about the large number of Viet Minh supply trucks reported en route to the area. “We can’t cut the trails,” he told the officers, many of whom disagreed.

11

Following mass that evening, Navarre presided over a holiday supper at de Castries’s quarters but left quickly when Lieutenant Colonel Jules Gaucher of the Ninth Groupe Mobile, a burly, no-nonsense veteran who had been in Indochina since 1940 and who during the evening had consumed his share of drink, described in unsparing detail the difficulties of conducting operations even a few miles from the camp. The next day, after the fog lifted, Navarre departed as quickly as he had come.

Why, in light of his gloomy realism, did he not call the whole thing off, order an evacuation? The hour was late, to be sure—the PAVN 308th and 316th Divisions were already establishing defensive positions to prevent a withdrawal. But Giap did not yet have artillery in place and would not for several weeks. There was still time. An order to evacuate would have been personally embarrassing and would have brought forth charges of weakness, of snatching defeat from the jaws of victory, of quitting just when decisive victory was at hand. But it would have generated support as well, including among politicos in Paris who had given him a free hand to act as he wished. History offered many examples of commanders who, when faced with an untenable situation, chose to retreat and were praised for their wisdom, despite fervent initial opposition to the action.