Empire of the Sikhs (8 page)

Read Empire of the Sikhs Online

Authors: Patwant Singh

Drumbeat of a School Drop-out

âThe Maharaja [Ranjit Singh] has no throne.

“My sword”, he observed, “procures me

all the distinction I desire.Ӊ

BARON CHARLES HUGEI.

Into this bloodied landscape of Punjab, Ranjit Singh, only son of Mahan Singh Sukerchakia and Raj Kaur, daughter of Raja Gajpat Singh of Jind, was born on 13 November 1780. He seemed an unlikely prospect as the founder of a kingdom. The people of the Punjab belonged to the tall, large-boned type settled in northern India since the Aryan migrations of around 1500 BC, physically distinctive in the region to this day. Ranjit Singh conformed to this type not at all. He was small of stature and slight of build, and in childhood his face was scarred by smallpox, which left him blind in one eye. In his early years he was nicknamed Kana, âthe one-eyed one'. As C.H. Payne, a chronicler of the Sikhs, put it: âThe gifts which nature lavished on Ranjit Singh were of the abstract rather than the concrete order. His strength of character and personal magnetism [were to be] the real sources of his greatness.'

1

A Western observer of the time wrote of âthe splendid mental powers with which nature had endowed him'.

2

As a child the boy does not seem to have occupied himself with any of the pursuits in which children of privileged circumstances

are apt to indulge or be indulged. Instead of giving his child playthings, his father is said to have handed him a sword. While he could never find the time to learn to read and write beyond the Gurmukhi alphabet, he eagerly learnt musketry and swordsmanship. The stories of the daring feats of his father, grandfather and others before them greatly influenced him and helped shape the course of his life.

The most colourful of his ancestors was a figure from the seventeenth century, Desu, a cultivator, his father's great-greatgrandfather. Desu's earthly possessions consisted of twenty-five acres of land, a well, three ploughs and two houses for his family and cattle. The Sukerchakia

misl

took its name from that of his village, Suker Chak, which was located near the town of Gujranwala, about forty miles north of Lahore.

An accomplished cattle-lifter, Desu was also known for his courage and derring-do; he was a giant of a man and a fearless fighter. The great love in his life was his piebald mare Desan, on which he would swim all the five rivers of Punjab when in flood. According to one account, he and Desan did this fifty times. At the age of fifty, Desu decided to go and see Guru Gobind Singh at Anandpur with the request that he baptize him. After the baptism his name was changed to Budha Singh, and, greatly inspired by the Guru, he stayed with him to participate in the many battles fought by the Khalsa. When he died in 1715 at Gurdas Nangal fighting alongside Banda Singh, there were twenty-nine scars of sword cuts on his body, seven bullet wounds and seven wounds from spears and arrows.

The two sons of this colourful man, Nodh Singh and Chanda Singh, were much less spectacular in their military exploits. But Nodh Singh's eldest son Charat Singh, Ranjit Singh's grandfather, stood out as a man of great stature both on the battlefield and because of the extent to which he expanded the territories of the Sukerchakias. His daring exploits attracted Abdali's attention, and

in clashes in 1761, 1764 and 1766 he tried to eliminate Charat Singh, but the indomitable

misl

chief emerged stronger than ever, making sure after each engagement to annex still more territories.

In his brief lifespan of forty-five years, he acquired the entire districts of Gujranwala, Sheikhupura, Jhelum, Shahpur, Fatehgunj, the salt mines of Khewra and Pind Dadan Khan and the much fought-over northerly fort of Rohtas. He also captured Chakwal, Jalalpur, Rasulpur, the towns of Kot Sahib Khan, Raja Ka Kot, parts of Chaj and Sind Sagar Doab and took many other territories under his control, such as parts of Rawalpindi, but in some cases he was content merely to receive revenue. By means of many other such arrangements he established his suzerainty, the Sukerchakia

misl,

over a considerable area. His power was won and consolidated not only by force of arms but through alliances entered into by marrying his sons, sister and daughters into families of consequence. The broad base he created was without doubt the springboard that was to enable his grandson to establish an empire of the Sikhs. Had it not been for his untimely death at forty-five, caused by the accidental firing of his own gun, this energetic man would have achieved much more.

Of his three children, his two sons Mahan Singh and Sahaj Singh and their sister Raj Kaur, it was Mahan Singh, born in 1760, who headed the

misl

and proved a worthy successor to his father who died when the boy was just ten. Until he took charge of the

misl

just five years later, his purposeful and able mother, Mai Dessan, handled its affairs and its extensive territories with exemplary skill, self-confidence and courage. She provided Mahan Singh with invaluable lessons in the management of his complex inheritance, lessons he put to good use. The problems she dealt with ranged from a revolt by senior officials appointed by the

misl

to winning the army's support of her stewardship and rebuilding Gujranwala Fort, the seat of the Sukerchakia

misl,

which had been destroyed by Ahmed Shah Abdali. Mai Dessan

finely exemplified the tradition by which Sikh women took on crucial responsibilities in critical times.

Married four years earlier (1774) to another Raj Kaur, later known as Mai Malwain, daughter of Raja Gajpat Singh of Jind, Mahan Singh soon set about expanding the territories of the

misl

still further. From the Bhangi

misl

he annexed Issa Khel and Mussa Khel, then went for the Chatha Pathans of Rasulnagar whose territories lay along the River Chenab and who were briskly building fortifications and townships there. To tame Pir Muhammad, who headed the Chatha tribe, Mahan Singh laid siege to Rasulnagar, which held out for several months but eventually gave in to him. The Pathan Chathas at that time were highly respected for their fighting qualities, and in the strong base they were creating for themselves along the River Chenab Mahan Singh saw a future threat to his

misl

's interests. Fortunately for him Pir Muhammad and his brother Ahmad Khan were bitter enemies, which enabled Mahan Singh to subdue them both, capturing their forts at Sayyidnagar and Kot Pir Muhammad as well as Rasulnagar.

Mahan Singh was on his way home after the siege of Rasulnagar when he received news of the birth of his son Budh Singh on 13 November 1780. The first thing the father did on reaching home was to change the boy's name to Ranjit â which not only meant âthe victor of battles' but was also the name of Guru Gobind's war drums: a prophetic change.

Mahan Singh was soon on the march again â this time to Jammu, in the Kashmir foothills. Through manipulative politics, inter

-misl

rivalries and clash of arms, Mahan Singh made his way to Jammu and ransacked it. Although he had agreed on a joint operation with the Kanhayia

misl

and an equal share in the booty, he left the Kanhayias out on both these counts. In their rapidly deteriorating relations the two

misls

frequently took to the battlefield, but in the end Mahan Singh's forces prevailed, and the

Kanhayia

misl

chief's son Gurbaksh Singh was killed in one of their battles, although at the hands of the Ramgarhias.

It should be noted that while the

misl

chiefs as a rule pooled their resources to fight an enemy they fought each other with equal zest if there was no enemy to take on. There are no known instances of a

misl

chief combining forces with a hostile regime or an invader to settle scores with a fellow

misl

chief, but conspiracies and changing alliances between the

misls

were constant, and in Mahan Singh's time he emerged the victor wherever he intervened. Whether he prevailed over his adversaries in an entirely upright manner or through deceit has been endlessly debated. Many chroniclers say he often resorted to treachery against those who opposed him, starting with Pir Muhammad and Ghulam Muhammad of the Chathas, Raja Brij Raj Singh Deo of Jammu and another member of the Kanhayia

misl,

Haqiqat Singh, and convincing reasons have been provided in support of their criticism. But much has been written in his favour, too. It does seem, however, that he was less principled than his father Charat Singh and his son Ranjit Singh.

What cannot be denied is that in his short span of twenty-nine years â he was felled by a sudden illness â he achieved far more than most other chiefs in those turbulent times. In addition to his legacy of expansion and consolidation, he set up an administrative structure for his

misl,

which was an overdue move few chiefs had attempted before. The first step he took was to appoint a

diwan

(minister) to handle everyday administration along lines specifically laid down. For his soldiery, for instance, he made a beginning by doing away with the spoils system, strictly enforcing the rule that whatever was plundered or seized as booty during a battle would be the property of the

misl

and not of individuals. All tributes and fines received would also accrue to the

misl

chief, not the officer in charge of operations. Records would also be maintained of all such income. In the same way, administration of territories

acquired was also thought of for the first time, although it was Mahan Singh's son who would establish a sound and enduring system of administrative control of the territories he added to his ever-expanding empire.

While some historians are of the view that Ranjit Singh was born in Gujranwala (now in Pakistan), one of the towns newly developed by the Sikhs, others are convinced he was born in Badhrukhan near Jind, his mother's home, about 250 miles south-east of Gujranwala. In the view of the historian Sir Gokul Chand Narang, who was an official in the British administration of Punjab in the years 1926-30, Ranjit Singh was âborn in 1780 in Gujranwala at a spot in the Purani Mandi near the office of Gujranwala Municipal Committee, marked by a date-palm tree and a slab put up there probably by the Municipal Committee'.

3

Several other British historians affirm Gujranwala as his birthplace. It has been claimed that up until 1947 a cradle was preserved in the room where Ranjit's mother was confined, an annual holiday being traditionally observed in Gujranwala on the date of her son's birthday.

4

The historian Hari Ram Gupta, on the other hand, categorically rejects this assertion and claims Badhrukhan as his place of birth. A pre-Independence British gazetteer of undivided Punjab states that âRanjit Singh ⦠was born at Gujranwala and he made it his headquarters during the years which preceded the establishment of his supremacy and his occupation of Lahore in AD 1799.'

5

There may be different views about the birthplace, but there is agreement among numerous accounts of the wild rejoicings that followed the news of the heir's arrival. Spectacular feasts and distribution of large sums of money among the poor continued for days on end in a city festooned with lights and alive as never before.

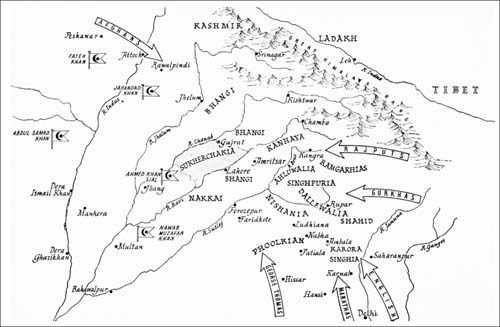

SIKH MISLS IN THE LATE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

Of Ranjit's earliest years little detail has survived, but there is ample confirmation of the fact that he was adored and indulged by his doting family. He was sent to Bhagu Singh Dharamsala (centre of learning) in Gujranwala, where he learnt no more than a few numerals and acquired some knowledge of how to follow maps and charts, which was to stand him in good stead throughout his life. He showed no interest in the arts, mathematics or book-keeping but was instinctively drawn to agriculture and other disciplines that required physical input. After just one year he left the Bhagu Singh Dharamsala. He zestfully set about learning the martial arts â especially how to fight with sword and spear. He also loved to swim, wrestle, shoot and hunt, perhaps sensing that these were not the times in which scholarly pursuits would get him far. He revelled instead in the acquisition of the skills he knew he needed to be a warrior and to lead troops into battle. A Brahmin, Amir Singh, an expert with guns, taught him how to handle a musket.