Empires of the Word: A Language History of the World (22 page)

Read Empires of the Word: A Language History of the World Online

Authors: Nicholas Ostler

Tags: #History, #Language, #Linguistics, #Nonfiction, #V5

*

This is known as the TaNaK(for

Tôrāh Ni’îm wa-Ks

ū

îm

, ‘Law, Prophets and Scriptures’). But besides that there is the commentary on the Torah known as the Mishnah (200 BC-AD 200), the supplement known as Tosephta (AD 300), and a verse-by-verse commentary on the TaNaK, known as the Midrash (AD 200-600). These show that Hebrew continued to be written as well as read.

*

It was written on clay tablets; this is why it survived. But it was incised in an alphabet based on cuneiform, so graphically too it throws an interesting light on the Phoenicians, until then reputed to have been the first to use an alphabet. The simpler shapes of the Phoenician letters are due to their usually being written with ink on papyrus, rather than stamped with an angled stylus on clay.

†

El is simply the Semitic root for ‘god’, seen also in Hebrew

elohīm

, one of the two words for God in Genesis, and Arabic

Al-lah

, literally “The God’.

*

The poem continues with listings of characteristic products for all the major client nations: Tarshish (metals); Greece, Tubal, Meshech (slaves, bronze working); Beth Togarmah (equines); Rhodes (ivory and ebony); Aram (turquoise, fine cloth, coral and rubies); Judah and Israel (wheat, honey, oil and balm); Damascus (wine, wool); Danites, Greeks of Uzal (wrought iron, cassia, calamus); Dedan (saddle blankets); Arabia, Kedah (sheep and goats); Sheba, Raamah (spices, gems, gold); Haran, Canneh, Eden, Asshur, Kilmad (clothes, fabric, knotted rugs).

*

Elimam (1977) suggests that the Punic story had a happier ending, and that Punic is still alive today, as the ancestor of Maghrebi ‘Arabic’ (

maghreb

is Arabic for ‘west’). It is certainly true that this Semitic language, usually characterised as a dialect of Arabic, diverges strongly from the classic language of the Koran; but this is true of all the Arab vernaculars. Where Punic did survive after the Roman period, it would very likely have made a significant contribution to Maghrebi. Unfortunately, the restricted evidence of what Punic was really like makes it hard to know to what extent this happened. Elimam himself suggests, on the basis of the longest Punic speech in Poenulus (ten lines, eighty-two words), that Punic has 62 per cent in common with Maghrebi, and a further 18 per cent has undergone some semantic evolution.

*

The return is recorded at length in the books Ezra and Nehemiah of the Bible. They are in Hebrew, though much of the correspondence with the government is given in Aramaic (Ezra iv.8-vi. 18 and vii. 12-26). It is an amazing demonstration of the preservative power of a tradition consciously maintained that now, after an absence of two and a half thousand years, Hebrew is again the vernacular on the streets of Jerusalem.

*

This momentum was known anyway, since India’s original scripts, Kharoshthi and Brahmi, are both derived from Aramaic writing. Since Brahmi in turn is the origin of every other alphabet in South and South-East Asia, the Persian king Darius was in effect setting the writing systems of most of Asia for the next 2500 years when he chose Aramaic as the standard language for his empire.

†

The French historian Fernand Braudel can hardly forgive him for missing his opportunity to go west instead, and so take over the Mediterranean (Braudel 2001: 277-84, ‘Alexander’s mistake’).

*

Matthew xxvii.74. Sawyer (1999: 84) quotes a lot of evidence for attitudes to Galilean.

†

The name

Urfa

is probably derived from

Hurri

(cf. the Greek name of its surrounding province,

Orrhoēnē

), with a history going back to the Mitannian period.

†

The Muslims in themselves were never a physical threat to the Aramaic speakers, since they saw them everywhere as

millet

, or distinct nationalities, separate but respected. But there was a tendency for Aramaic speakers everywhere to give up everyday use of the language in favour of Arabic.

*

Christians were not the only people to go on speaking Aramaic, though they have lasted longest. The Gnostic sect of southern Mesopotamia also spoke another dialect of Aramaic, known as Mandate or Mandaean, at least until the eighth century. And for a few centuries AD, the Jews of Babylonia and Persia also continued, producing most notably the vast Babylonian Talmud. Both these communities were prolific in writing literature.

†

There is a considerable modern diaspora too, to the major cities of Israel, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Iran and Turkey. Many are said to have emigrated to Armenia and Georgia after the Russo-Persian war of 1827; and a sizeable number have gathered in the USA. The use of the Internet in binding them together is examined in McClure (2001). She quotes estimates of worldwide numbers around 1-3 million.

§

Its name is derived from Arabic

qibt

, ‘Egyptian’, a shortening of the Greek

Aigyptios.

*

This caused some philological problems, since Muhammad’s dialect of Arabic was slightly nonstandard: it lacked the glottal stop ’, known as

hamza

(the stop heard in place of the tt of the London pronunciation of ‘bitter’), had lost the -n ending of the nominative, and had turned the -t ending of feminine nouns into -h. The scholars wanted to retain the text exactly as written, but recite it according to the rules of standard Arabic. As a result, all these consonants of Arabic had to be inserted in the written text with special accent marks, as if they were vowels. These marks are all now standard in Arabic spelling.

*

Arabic script turned out to be much more universally attractive than its language, and has been taken up wherever Islam was accepted. This has happened despite its functional weaknesses, with no marking of vowels or tones, and a need for elaborate accents even to distinguish all the consonants. Nevertheless, compromises have been found, and it has been applied to languages as various and as unrelated as Persian, Turkish, Kashmiri, Berber, Uighur, Somali, Hausa, Swahili and Malay, as well as Spanish and Serbo-Croat. It must owe this success to the fact that literacy in Muslim countries finds its alpha and its omega in the sacred text of the Qur’ān in Arabic script; so any other writing system can only be an extra complication.

*

It may be worth noting that the j in this word is pronounced as in

judge.

†

But one is left wondering why the linguistic approach of the Germans, notably the Visigoths, had been so different, when in 410 they likewise took over control of the neighbouring higher civilisation, the Roman empire, only to cast themselves, almost immediately, as its protectors. But in the European case, there was no third language playing the role of Persian: Latin was still the only language of temporal power, as well as the language of the Roman Church.

*

Hausa, centred on Kano in northern Nigeria, is more of a problem for the constraint. It has certain features that are reminiscent of Arabic, e.g. two genders, masculine and feminine, the latter marked with -

a

(cf. Arabic -

ah

); and the absence of

p

—as in Arabic, it usually replaces

p

in loan-words with

f.

Moreover, its predominantly Muslim speakers have filled it with loan words from Arabic, including most of the numerals above ten, and the days of the week, and even some productive prefixes, such as

ma

-. (’School’ is

makaranta

, formed from

karanta

, ‘read’, itself related to the word

Qur ‘ān.

In Arabic, ‘school’ is

maktab

, or

madrasa

, with the same prefix, but ktb, ‘write’, or drs, ‘lesson’, as the stem.) But it also has many features much more typical of its African neighbours, e.g. three contrasting tones, and explosive consonants. It may be that its own utility as a lingua franca, widely used in West Africa and not just among Muslims, has acted to maintain its independence.

*

They even plied, especially in the early centuries, to South-East Asia and China.

Abū Zayd of Sīrāf

wrote that sea traffic in 851 was regular because of a great exchange of merchants between Iraq and markets in India and China: in fact, he said, a trade colony of 120,000 Westerners (including Muslims, Jews, Christians and Zoroastrians) were massacred in Canton in 878 (Hourani 1995: 76-7).

*

Zanzibar is in fact an Arabised form of Persian:

Zangi-bar

, ‘blacks’ land’.

*

In Turkish spelling (introduced by Atatürk in 1928-9),

c

is [dž] (j in

judge

),

ç

is [č] (ch in

church

),

i

is i pronounced with the tongue root drawn back (as in Scots

kirk

), and

ğ

is either a gargling sound (like Greek gamma or Arabic ghain) or just a lengthening of the preceding vowel;

ö

and

ü

are as in German.

Triumphs of Fertility: Egyptian and Chinese

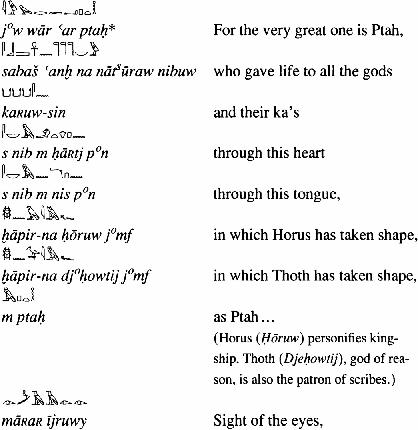

*

In the interests of readability and realism, Egyptian words are given according to the reconstruction of Loprieno 1995 for early Middle Egyptian, with the addition that vowels that he believes indiscernible are represented here by °.

R

is the French (or Israeli) uvular r, and

j

is pronounced as in German, like English y in

yet.is a deeper h, as when huffing on a pair of glasses; and

is like ch in ‘loch’ or ‘Bach’.’ is ayn, notorious from Semitic languages, the throat-clearing sound at the beginning of English ‘ahem’. It should be remembered, however, that as written in hieroglyphs, Egyptian words are totally without vowels.