Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber (50 page)

Read Enchanted Evenings:The Broadway Musical from 'Show Boat' to Sondheim and Lloyd Webber Online

Authors: Geoffrey Block

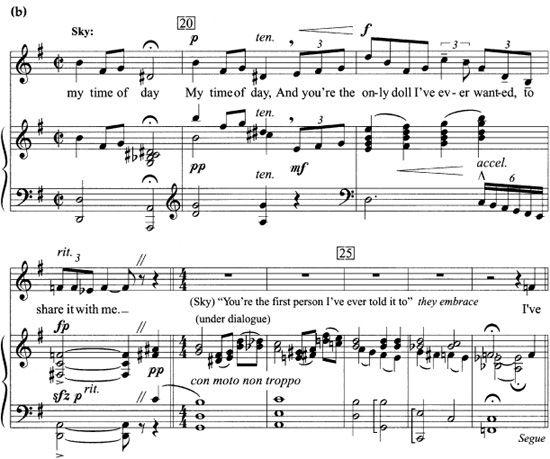

After audiences learn from his dialogue with Sarah that Sky’s interest in and knowledge of the Bible sets him apart from the other “guys,” his music

tells us that he is capable of singing a different tune. His very first notes in “I’ll Know” may depart from Sarah’s lyricism, metrical regularity, and firm tonal harmonic underpinning, but after Sarah finishes her chorus, audiences will discover that Sky shares her chorus and verse as well as chapter and verse. Following Sarah’s more “doll-like” acknowledgment of her changing feelings toward Sky in “If I Were a Bell,” Sky is almost ready to initiate their second duet, “I’ve Never Been in Love Before.” But first he needs to tell Sarah in “My Time of Day” (predawn) that she is the first person with whom he wants to share these private hours. The metrical irregularity, radical melodic shifts, and above all the harmonic ambiguity that mark his world before he met Sarah capture the essence of Sky’s dramatic as well as musical personality.

The twenty measures of this private confession (the opening and closing measures are shown in

Example 11.1

) is stylistically far removed from any other music in

Guys and Dolls

. After the first chord sets up F major, Sky’s restless nature will not allow him to find solace in a tonal center. By the end of his first phrase on the words “dark time,” he is already singing a descending diminished fifth or tritone (D to A ) which clashes with the dominant seventh harmony on C (C-E-G-B

) which clashes with the dominant seventh harmony on C (C-E-G-B ) that pulls to F major. Only when Sarah becomes the first person to learn Sky’s real name, the biblical Obediah, will the orchestra—as the surrogate for Sky’s feelings—return the music to F major. But now F is reinterpreted as a new dominant harmony instead of a tonic and serves to prepare a new tonal center, Bb major, and herald a new song, “I’ve Never Been in Love Before.”

) that pulls to F major. Only when Sarah becomes the first person to learn Sky’s real name, the biblical Obediah, will the orchestra—as the surrogate for Sky’s feelings—return the music to F major. But now F is reinterpreted as a new dominant harmony instead of a tonic and serves to prepare a new tonal center, Bb major, and herald a new song, “I’ve Never Been in Love Before.”

Even when Sky sings his own music rather than Sarah’s, he shows his closeness to her by avoiding much of the metrical, melodic, and harmonic conventionality and syncopated fun of the other “guys.” In his song for the souls of his gambling colleagues in act II, “Luck Be a Lady,” syncopation is reserved for the ends of phrases, and his music, compared to the music of the tinhorns Rusty, Benny, and Nicely-Nicely, is contrastingly square. The marriage of Sarah and Sky at the end of the show is thus made possible (and believable) by the compromising evolution of their musical personalities. Just as Sarah becomes more like Sky and his world, Sky moves closer to Sarah’s original musical identity.

Example 11.1.

“My Time of Day”

(a) opening

(b) closing

Before their individuality is established Sky and Sarah are introduced more generically in their respective worlds in one of the most perfect and imaginative Broadway expositions, an opening scene that includes “Runyonland,” “Fugue for Tinhorns,” “Follow the Fold,” and “The Oldest Established.” The ancestor of “Runyonland” was Rodgers and Hammerstein’s

Carousel

, which opened with an inspired pantomimed prologue—

Guys and Dolls

also includes an independent overture—that set up an ambiance and allowed audiences to place Julie Jordan’s subsequent denial of her feelings in perspective. As we have seen in

chapter 9

, the

Carousel

pantomime focused on establishing the relationships between the central characters, Julie and Billy Bigelow, and the jealousy their romance will arouse in the carousel proprietress, Mrs. Mullin.

The musical component of the pantomimed “Runyonland” is a medley of the title song, “Luck Be a Lady,” and “Fugue for Tinhorns” in various degrees of completeness and altered tempos. Inspired by Kaufman’s admonition to “take a deep breath and set up your story,” the opening devotes itself entirely through narrative ballet and mime to capturing the colorful world of Runyon’s stories. The scene description in the libretto and the published vocal score details an intricate comic interaction of con artists, pickpockets, a man who pretends to be a blind merchant, naive tourists, bobby soxers, and a prizefighter who is inadvertently knocked down by the unimposing Benny Southstreet, the only named character to appear in this elaborate sequence. At the end of “Runyonland” we meet two other tinhorns, Rusty Charlie and Nicely-Nicely Johnson, the latter of whom will emerge, after Sky, as the leading male singer of the evening. In a transition that literally does not skip a beat, the trio introduce the first song of the show, “Fugue for Tinhorns.”

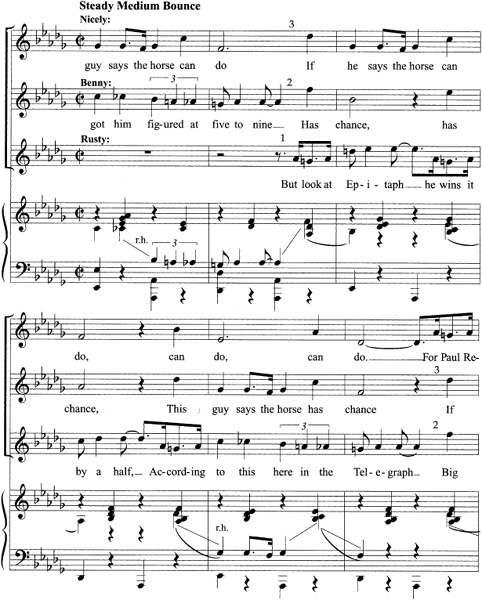

Tinhorns are gamblers who pretend to be wealthier than they are. Burrows’s and Loesser’s tinhorns match this description with their pretense to a verbal and musical sophistication they do not possess. The verbal pretensions are evident throughout their dialogue, the musical ones are most clearly revealed in their opening song. Even the word “fugue” is pretentious, referring to a musical form associated with J. S. Bach in which similar melodic lines, introduced at the outset in staggered entrances of a principal melody (known as the fugue subject), are then heard simultaneously. True to type, what Rusty, Nicely-Nicely, and Benny sing is in fact not a fugue at all but a form that pretends to be a fugue, the lowlier round, known to all from “Three Blind Mice” and “Row, Row, Row Your Boat.”

In the first of many departures from a fugue, the participants in a round begin by singing the identical (rather than a similar) musical line, albeit also

in staggered entrances. The whole tune of Loesser’s “fugue” consists of twelve measures of melody, with the final eight measures containing additional repetition. Despite their relative simplicity, rounds are tricky to create, since they must be composed vertically (the harmonic dimension) as well as horizontally (the melodic dimension). In “Fugue for Tinhorns” Loesser therefore has constructed his twelve-bar tune so that it can be subdivided into three four-bar phrases (one complete phrase is shown in

Example 11.2

); each phrase is constructed so that it can be sung simultaneously with any of the others. In order to squeeze a horizontal twelve-bar melody comfortably into a vertical four-bar straitjacket, the harmony must not change. The entire musical content therefore consists of repetitions of harmonically identical four-bar phrases, alternated among the three participants, each of whom argues in favor of his chosen horse, Paul Revere, Valentine, and Epitaph.

Guys and Dolls

, Crap game in the sewer in act II. Robert Alda throwing the dice, Stubby Kaye kneeling to the left, Sam Levene to the right (1950). Museum of the City of New York. Theater Collection.

Even though Loesser does not produce a real fugue, he does offer a degree of real counterpoint that is unusual in a Broadway musical, especially a musical comedy. In fact, the only substantial use of counterpoint

among earlier musicals surveyed in this volume occurs, not surprisingly, in

Porgy and Bess

(a technique also demonstrated in earlier Gershwin shows not discussed here, perhaps most notably in “Mine” from

Let ’Em Eat Cake

). Prominent but relatively isolated additional examples can be found in Blitzstein’s

The Cradle Will Rock

(scene 10) and Bernstein’s

Candide

(“The Venice Gavotte”) and

West Side Story

(the “Tonight” quintet). After 1970 this device would become more prominent in Sondheim (e.g., the combination of “Now,” “Later,” and “Soon” in

A Little Night Music

). Even straightforward harmonization between two principals is exceptional in the musicals of Kern, Rodgers, Porter, and Loewe. Interestingly, the only Broadway composer to rival Loesser at the counterpoint game was Berlin, another lyricist-composer with less formal musical training than the other composers discussed in the present survey, Loesser included. In songs that ranged throughout his career, most famously “Play a Simple Melody” from

Watch Your Step

(1914), “You’re Just in Love” from

Call Me Madam

(1950), and his final hurrah as a composer, “An Old-Fashioned Wedding” from the 1966 revival of

Annie Get Your Gun

, Berlin created extraordinary pairs of melodies that could be sung simultaneously.

Example 11.2.

“Fugue for Tinhorns” (one complete statement of three-part round)