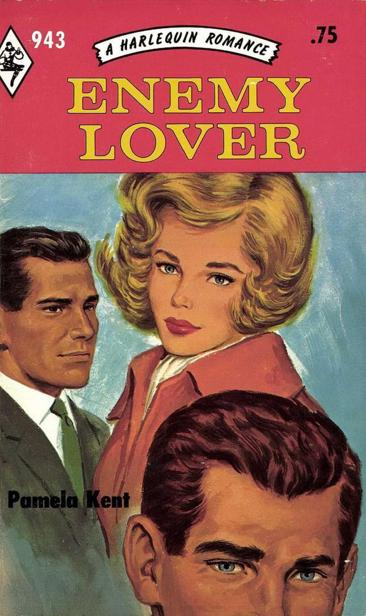

Enemy Lover

Authors: Pamela Kent

by

SBN 373-00943-7

CHAPTER ONE

THE light was already fading when Tina stood at the schoolhouse door and watched the last of her pupils walking away from her. She wished she had sent them home earlier, but four o’clock in the afternoon was the usual hour for this remote part of the world. Fortunately, only Johnny Gains had any real distance to go, and he was used to the long walk across the moor to his father's remote

cottage.

Even so, she suddenly couldn’t bear the thought of Johnny going forth into the dusk with a threat of snow in the air, and no one to give him a helping hand if he blundered into a bog.

“Wait, Johnny!” she called, and darted back into the house to fetch her own coat and a head-scarf. “I’m coming with you,” she told him, as she clasped his small hand, and he showed her his two broken front teeth in a relieved grin while the other children melted into the dusk, and soon even the sound of their chattering voices and their little bursts of laughter died into silence.

There was a piercingly cold wind cutting across the moor, but Tina tucked her coat collar up about her ears, and she wound Johnny’s thick woollen scarf tightly about his neck. They kept their heads bent and, in order to make the distance seem shorter, recited scraps of doggerel as they walked

“We folk, good folk,

Trooping all together;

Green jacket, red cap And white owl’s feather...

“Down along the rocky shore some make their home;

They live on crispy pancakes of yellow tide foam.”

“What is yellow tide foam?” Johnny wanted to know, but Tina was wondering whether she had locked the door behind her before she left, and she answered vaguely. In any case, she thought, it didn’t greatly matter, for no one would be tempted by a pile of uncorrected school-books; and her own personal things would have very little more appeal.

Mis. Macartney had baked her a cake during the afternoon, and it was on the kitchen table. Someone might be tempted by that... She had a Golden Treasury of Verse which she prized, and a couple of slim volumes which her father had said might fetch money one day. She had a new coat with some pseudo-mink on the collar, and a small portable radio that had cost her more than she could afford.

On the whole, it might have been better if she had made absolutely certain that she had turned the key.

However, it was too late now, and they were at Johnny’s cottage, and Johnny's mother was both surprised and relieved when she saw her offspring accompanied by the young woman who corrected his cramped handwriting. She insisted on Tina staying for a cup of tea before she set off again into the night, but by this time it was very dark indeed, and Tina had the utmost difficulty keeping to the narrow tracks without a torch.

She remembered the night—now a couple of months ago— when she had unwisely ventured on to the moor without a torch. On that occasion she might have run into difficulties but for old Angus Giffard’s light shining out into the dark. She had been surprised to see it, at ten o’clock at night, for old Angus adhered to a routine that never varied, and he was usually in bed and deeply sunk in his second sleep by ten o’clock.

On this night, however, the light from his oil lamp had shone out like a guiding star into the night. His cottage was very small, and all the rooms were on the ground floor. The kitchen was on a corner, and Tina could see into it when she opened the garden gate and stole up the little path silently. She looked between the faded curtains and she saw old Angus slumped across the table, either asleep or ill.

She was never quite able to get over the miracle of one of the windows being left unlatched, for old Angus was intensely suspicious of his fellow creatures, and she was able to climb over the sill and into the house. There she found brandy and hot-water bottles, and got old Angus to bed. He was in very poor shape, his lips blue, his eyes glazed, but she worked over him until dawn, when she felt it safe to leave him. Then she set off across the moor in the angry primrose light to fetch the doctor at Little Connors, and after that she went back to the schoolhouse to open school.

Old Angus was critically ill for a week, and during that week she visited him every day and took him baskets of nourishing foodstuffs like egg custard and chicken jelly. The chicken jelly she made herself, and reinforced it with a glass or two of the best sherry she could obtain locally. She also read to him, and discussed items of news in the newspapers—and old Angus argued fiercely about politics (or would have argued, if she had let him). He told her she was a remarkable young woman, although he thought she was much too young for a schoolteacher, since children needed

discipline and lots of good, hearty spankings. Old Angus had no time at all for the modern tendency to ‘spare the rod’. In point of fact, he had little time for anything apart from his own unsociable way of life, and his narrow-minded views on most things. Governments were wrong, policies were wrong, development was wrong... the whole world was wrong! But old Angus had the key to perfect peace and contentment if only people would leave him alone.

He subsisted on the very minimum in the very maximum of discomfort. He had few possessions apart from books and an old cabinet gramophone; yet he spoke several languages with the fluency of one who had used them often, he had travelled widely, and his air was the air of an autocrat who should have had servants to order about.

No one locally knew much about him, and the little that was known was not noised abroad. Tina thought of him as a poor, if disgruntled old man who needed care and attention, and she was not altogether sorry when she heard that relatives had whisked him away and his cottage was empty.

She was sorry for the loneliness of the cottage whenever she passed it, but otherwise it was old Angus’s cottage... And no one had gone near it to do a thing about it since he left. As she passed close to it tonight, on her way back to the schoolhouse, she thought that she herself would have to do something some time, if no one else did. There must almost certainly be a lot of clearing up to do, for it was hardly likely he would have left the place very tidy.

She would have been glad of a light shining out from the kitchen window, but there was nothing but the pale reflection of the moon as it struggled through banks of low-lying clouds and endeavoured to bathe the whole lonely landscape in some sort of radiance.

But if there was no light in Angus’s cottage, there was a light in the schoolhouse when she reached it. Tina’s heart gave a startled leap when she caught sight of it, and when she caught sight of the long, sleek car outside the unpainted iron gate she could hardly believe her eyes.

The tiny schoolhouse nestled in a fold of the hills, and hardly anyone came to it at night, unless it was Mrs. Macartney to enquire whether Miss Andrews could do without her the following day, or something of the sort. But Mrs. Macartney had certainly never driven in such a car as now stood at the gate, and she would have been utterly overcome by the sleek magnificence of it, if she had been permitted to gaze at it with the yellow lamplight shining out and discovering answering beams in the bonnet.

Tina herself stood still to inspect it for a moment before she entered the house. There was no one inside the car. Whoever moved it—or whoever had driven it to this faraway spot—was inside and waiting for her.

There was no need to turn the handle of the front door, for it was standing partly open. The schoolroom door was shut fast, but someone was moving about in her sitting-room, casting a shadow on the whitewashed wall. She could make out the head and shoulders of a man—a tall man—and he was bending to inspect the contents of her bookcase when she nervously and almost stealthily pushed wider the sitting-room door.

There was a tiny fire in the grate, and it was leaping and keeping company with the lamplight. The lamp stood on a centre table, and because someone inexperienced had lighted it it was smoking a little, and the first thing she did—even before asking her uninvited visitor who he was—was to adjust the wick. The man spoke critically.

“I didn’t know oil lamps were still used, even in parts like this. Can’t the local authorities run you up a cable, so that you’d at least have the benefit of electric light ?”

Obviously he thought the other ‘benefits’ she enjoyed were few.

Tina removed her head-scarf while she answered mechanically:

“We’re having electricity installed in the summer. It’s not very long to wait.”

The man’s smile was a little incredulous, as if he thought a young woman who must be still in her early twenties slightly abnormal if she could accept waiting a few months for anything with so much complacence. Denuded of her head-scarf her hair was soft and fluffy about her face, with the soft fluffiness of a day-old chick and the pale colour of a primrose and her eyes were blue.

The man, who was dark and slender and elegant, and who wore a heavy topcoat with the collar well up about his ears, gazed at her curiously for several seconds, as if he had been uncertain of what he would find here, and he was still not at all certain of what he had found.

“Who are you?” she asked, with sudden sharpness. “And what right had you to walk in here without waiting to receive an invitation?”

“You left the door unlocked.”

“I know. At least, I was afraid I had left it unlocked ... I went off in rather a hurry.”

“Then you mustn’t be surprised if you find someone waiting for you when you get back.”

“It’s never happened before.”

“Perhaps you’ve never left the door unlocked before.” He glanced at the darkness beyond the windows. “It doesn’t seem altogether wise in a spot like this.”

“I’m as safe here as I would be in a town. Possibly safer.” Once again he glanced at her, and his glance lingered. There seemed to be very little of her, but she was fashionably slender... He would have said too fashionably slender. But then he was a doctor, and he disapproved of dieting, and excessive thinness. She had a delicate face with fine bones, but there were slight hollows in her cheeks and her eyes were a trifle over-large. No doubt she lived on tinned soups and cups of coffee. In a benighted place like this who could blame her?

Once more he glanced at the dark outline of the window, at the bare room, at the lamp the still smoked, and he shuddered inwardly.

“I’m not going to introduce myself,” he said. “At least, not at the moment, but I would like you to understand that this matter is urgent. Were you ever acquainted with an Angus Giffard?”

She looked surprised.

“The old man who lived in the cottage? I knew him as Angus... I don’t think I ever heard his surname.”

“Well, you’ve heard it now. Angus Diarmid Ian Giffard, of Giffard’s Prior, about fifty miles from here. Will you come with me at once, because he wants to see you, and I don’t think he has very much longer to live. A day or so at the outside ...”

Tina was thrown into a state of utter stupefaction. That anyone should want to see her at. this late hour of the evening was extraordinary; that she was to be driven fifty miles in order that that person could see her was fantastic, and that it should be old Angus ... and he was dying.

“I’ll come with you,” she said, and asked only that she should be allowed to change into something more suitable for the journey, and that she should be back at the schoolhouse in time to open it for school the following day.

“I’ll drive you back myself,” her unknown visitor promised. “And this time I’d recommend that you lock the door, and take the key with you. I’ll look after it for you if you’d care to entrust it to me.”

CHAPTER TWO THE car had a maximum speed that took Tina's breath away when she heard of it, but mostly they travelled at considerably below that for the greater part of the journey. In any case, fifty miles was not a very great distance, and in such a car it was hardly noticeable.

Tina sat huddled in her new coat with the false mink on the collar in the seat beside the driver, and she marvelled at the ease with which he manipulated the gears that seemed to be attached to the chromium-plated wheel, and was a little oppressed by his silence. They sped through the night with the noiselessness and ease of a bird on the wing, skimming over unseen highways and diving into clumps of woodland, while around them lay still sheets of water that reflected the starshine, and the endless lonely stretches of the moor that were bounded by faraway bens.

Outside it was bitterly cold, and the threat of snow was still there; but inside the comfort and luxury of the car it was beautifully warm. If it had not been for the fact that her companion was a stranger and she had no real idea of where she was being taken Tina could have seized the opportunity to relax her overtired limbs and lain back against the expensive upholstery and dozed for at least twenty-five of the fifty miles. Her companion spoke to her occasionally.

“I think you ought to be put into the picture,” he said. “Old Angus is very ill, as I’ve told you, and he’s not expected to live. In any case, he’s nearly eighty... Hardly anybody ever guesses it, of course. His sister is with him, and his nephew. I’m a kind of distant nephew. My name is also Giffard.”