Enemy on the Euphrates (29 page)

Read Enemy on the Euphrates Online

Authors: Ian Rutledge

On learning of the nationalists’ intention to present their madhbata, Wilson agreed to a meeting with the delegates at the Baghdad serai, the headquarters of the British Civil Administration, on 2 June. However, claiming that the fifteen nationalist delegates were merely a group of ‘self-appointed politicians’, he also invited forty prominent ‘moderate’ Baghdadis who would, so he hoped, overwhelm radical opinion in a show of pro-British enthusiasm.

On the evening of the great event, Wilson, accompanied by the military governor of Baghdad, Colonel Balfour, the judicial secretary Bonham Carter and Lieutenant Colonel Howell, the revenue secretary, arrived at the serai in their well-pressed uniforms and solar topees. The occasion got off to a bad start: outside the building they were met by a crowd of rowdy school students and townsmen who shouted abuse at them. Inside, the atmosphere, like the actual temperature, was torrid. Over 100°f in the shade, the angry mood of the delegates and their supporters was exacerbated by the Ramadan fast, exceptionally trying when it fell in the summer period.

58

Moreover, once inside the serai, Wilson and his entourage were disconcerted to find that only a handful – nine, actually – of the forty pro-British notables, had dared to turn up. It was clearly going to be a difficult encounter. Nevertheless, undaunted by the evident failure of his plan to pack the meeting, Wilson – whose self-assurance had recently been fortified by the award of a knighthood – proceeded to hold

forth at great length and with considerable aplomb in English, followed by an Arabic text which had been prepared by Gertrude Bell.

Firstly, Wilson informed the meeting that he welcomed the opportunity of explaining the British government’s policy ‘in this matter’ and reminded the assembled notables of the Anglo-French Declaration of 8 November 1918 and Article 22 of the League of Nations Treaty, adding, ‘These declarations represent the policy of H.M.’s Government from which it has at no time diverged.’ Wilson then proceeded to read out

in extenso

the text of these documents, documents which were already perfectly well known to the educated and, in some cases, elderly men who stood facing him in the sweltering early evening heat.

After this colourless preamble, Wilson continued by assuring his sceptical audience that, ‘H.M.’s Government’s desire is to set up a National Government in this country and it is their intention that this shall be done as soon as possible.’ He then declared:

No one regrets more than I do the delay that has occurred. It is due to causes beyond our control – the prolongation of the war, the difficulties of making peace and the disturbed conditions of our borders both towards Persia, towards Turkey, and towards Syria have prevented a Civil Government being established here as quickly as we could wish, but I would not have you believe that this delay could have been avoided.

But then he adopted a harsher tone.

I can assure you that those individuals in Baghdad who have sought from patriotic or other motives to hasten the establishment of a Civil Government here by incitements to violence and by rousing the passions of ignorant men are doing and indeed have already done a great disservice to the country … Those who are encouraging disorder and inciting men against the existing regime are arousing forces which the present Administration can and will control … It is my duty as the temporary head of the Civil Administration to warn you that any further incitements to violence and any further appeals to prejudice will be met by vigorous action both from the Military authorities and the Civil Administration.

59

There had been no ‘incitements to violence’, as Wilson himself knew; but he apparently thought the Baghdad nationalists and their supporters could be cowed by his stern admonitions and menacing references to ‘vigorous action’. And so he went on:

We have the power and the intention to maintain order in this country until a Civil Government is established. I shall not hesitate to ask the Military authorities to apply any degree of force necessary to ensure this and they will not be backward in meeting my requests. It is my earnest hope that I shall not again have to say this to you and that there will be no further occasion for the use of troops or for the adoption of other special measures to maintain public order.

Then, turning to the question of ‘the future form of Government to be established in this country’, Wilson announced that ‘public opinion’ would be ‘consulted … as soon as we can do so’, and that his own proposal for a ‘Provisional Civil Government’, the details of which HM Government had not yet seen fit to authorise him to publish, would include the establishment of a ‘Council of State under an Arab President to hold office until the question of the final constitution of Iraq has been submitted to the Legislative Assembly which we propose to call’.

The scheme for a provisional government had been drawn up, two months earlier, by a committee chaired by the judicial secretary and composed entirely of other members of the Civil Administration. It would function ‘until we have had time in consultation with you to devise a permanent scheme’. The ‘Council of State’ would consist of a president and eleven members ‘each appointed by the High Commissioner and removable from the Council at his pleasure’. The president would be an Arab – chosen by the British, as would be any Arab members of the council; however, ‘we contemplate that, in practice, a majority of the [Council] members would be British.’ The provisional government would only be responsible for internal affairs. ‘External affairs, foreign relations, including treaties and war should be reserved to the Mandatory Power.’ And lest any of his audience thought that the formation of this

British-dominated ‘Provisional Civil Government’ would swiftly lead to any more meaningful form of self-representation, Wilson concluded as follows: ‘Do not be misled by appearances. Iraq has been under an alien Government for 200 years and with the best will in the world an indigenous National Government cannot be set up at once. The process must be gradual or disaster is certain.’

Sitting down, Wilson thanked the Arab delegates and their supporters for listening to him ‘so patiently’, adding that he would now be ‘glad to hear any representations you may wish to make’.

At this, the elderly Yusuf Suwaydi stepped forward. He was a man of average stature, a rather delicate face with a short, neatly trimmed white beard and large, piercingly dark eyes. He wore the dark blue cloak and small conical cap surrounded by a white turban of a Sunni qadi; his general demeanour was calm and dignified and as he prepared himself to speak a total silence fell over the assembled crowd. Addressing Wilson and his entourage directly, he reminded them that he and his fellow delegates had been chosen ‘by the people’ on the night of 7 Ramadan to represent them in discussions with the occupying power and to ‘negotiate with its representatives the implementation of three demands which were considered essential by the mass of the people and the majority of its leaders’.

Firstly, we demand the immediate establishment of a Convention representing the Iraqi people which will lay out the route whereby the form of government and its foreign relations will be determined. Secondly, the granting of freedom of the press so that the people may express their desires and beliefs. And thirdly, the removal of all restrictions on the postal and telegraph services, both between different parts of the country and between Iraq and neighbouring countries and kingdoms, to enable the people to confer with each other and to understand current world political developments.

60

Suwaydi then concluded, ‘In our capacity as delegates of the people of Baghdad and Kadhimayn, we ask that you agree to the implementation of these three demands as quickly as possible.’

There was, however, one notable omission from Suwaydi’s three demands. There was no mention of a request for one of the sons of Sharif Husayn to be installed as Emir of Iraq. Possibly this was simply one of the issues which would be settled by the ‘Convention’. But it seems equally likely that the nationalist leaders both in Baghdad and on the Euphrates were fast becoming disenchanted by the lukewarm response they had so far received from Husayn and the absence of any response at all from their hitherto favourite candidate, ‘Abdallah.

After Suwaydi had spoken, Wilson politely thanked the delegates for expressing their opinions but informed them that nothing further could be done until he received detailed instructions from London as to how the mandate was to be put into practice. Then he marched out of the serai; but as he did so he was met, once again, by a crowd of rowdy demonstrators, booing and shouting.

The very next morning, Hasan Sukhail, one of Gertrude Bell’s circle of pro-British notables, arrived at her office; the news he was bringing was not encouraging. He had not been at the madhbata but he had heard all about it – it was the talk of the town.

61

‘No one will accept the Mandate’, he declared and he warned her that there was no point in trying to set up the toothless ‘Divisional Councils’ which Wilson favoured since no one would serve on them: ‘The ashraf here, at present, are all determined to resist the mandate,’ he warned. And then, more ominously, Sukhail urged that the British must take the initiative in resolving the crisis immediately:

They say you have no troops now; that they are all dispersed and you can do nothing. I think it would be very difficult for you if they create disturbances up and down the country, attacking motor cars and cutting railways, You must act now. Today there will be 5,000 people in Kadhimayn; at the next meeting there will be 10,000. Such gatherings are difficult to control.

62

Nevertheless, in spite of this dire warning, which Bell immediately passed on to Wilson, a few days later both of them were taking a relatively relaxed view of the state of internal security. On 7 June Wilson

telegrammed the India Office, with copies to the government of India’s Foreign and Political Department at Simla and the high commissioner, Cairo, informing them that ‘the situation in Baghdad itself has somewhat improved during the last few days. Moderate opinion condemns the extremists. The public feels itself to be misled.’

63

For her part, Bell wrote to her father on the same day, telling him – in complete contradiction to the report by Hasan Sukhail – that Wilson’s reception of the madhbata had been a great success. ‘A.T.’s speech took the wind out of the sails’ of the delegates and that ‘the general talk of the bazaars was that the town had made a fool of itself. This impression continues to grow.’

64

And demonstrating the extent to which she was out of touch with events in the Shi‘i heartland, Bell added that at Najaf, ‘they had definitely refused to send up delegates to ask for Arab Independence.’ In reality, the Najafis had not sent delegates for the simple reason that they feared they would be arrested.

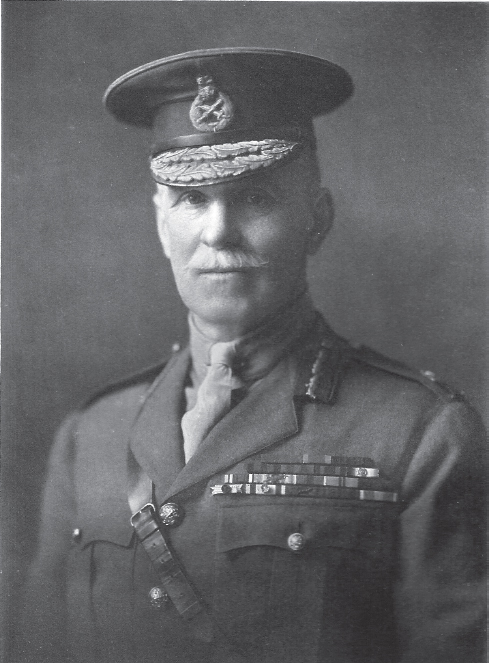

General Aylmer Haldane, British Commander-in-Chief in Iraq, 1921

General Haldane’s Difficult Posting

Monday 2 February 1920: it is a bitterly cold winter’s day and Winston Churchill, secretary of state for war, with his hands in his pockets and his coat-tails resting on his forearms, is warming his backside, standing before a blazing coal fire in his office in Horse Guards Avenue.

1

Opposite him, seated in a comfortable armchair, is Lieutenant General Sir Aylmer Lowthorpe Haldane, formerly commander of the 6th Army Corps on the Western Front, but who has been languishing on half-pay since the end of the war and for the last twelve months anxiously waiting for ‘something to turn up’. A few weeks earlier Haldane was informed that he will be appointed GOC-in-chief in occupied Iraq and now he has been called to the War Office to receive his instructions. But the meeting is not going to be a comfortable one. There is bad blood between the two men going back to an incident during the Boer War.

Churchill and Captain (as he was then) Haldane of the Gordon Highlanders had originally been close friends. On the morning of 15 November 1899, Churchill, who had previously resigned his commission as a lieutenant in the 4th Hussars and was now the war correspondent for the

Morning Post

, had joined Haldane on an armoured train at Estcourt, the most forward position of the British Army in Natal, to carry out a reconnaissance of the enemy positions. This was not a role suited to an armoured train and it was soon ambushed and derailed by a superior force of Boers equipped with artillery and Maxim guns. In the ensuing fighting, during which Churchill distinguished himself trying to evacuate some of the British wounded, he was captured along with Captain Haldane.

2

They were taken to a prisoner-of-war camp in Pretoria. Churchill and Haldane were both miserable as prisoners and together with a sergeant major named Brockie they began to discuss the prospects for escaping. Soon Haldane came up with a plan. He had discovered a part of the perimeter fence near the latrines where the iron palings were low enough for them all to climb over and jump into the dense undergrowth outside the camp. From there they would make their way to Portuguese-controlled territory.