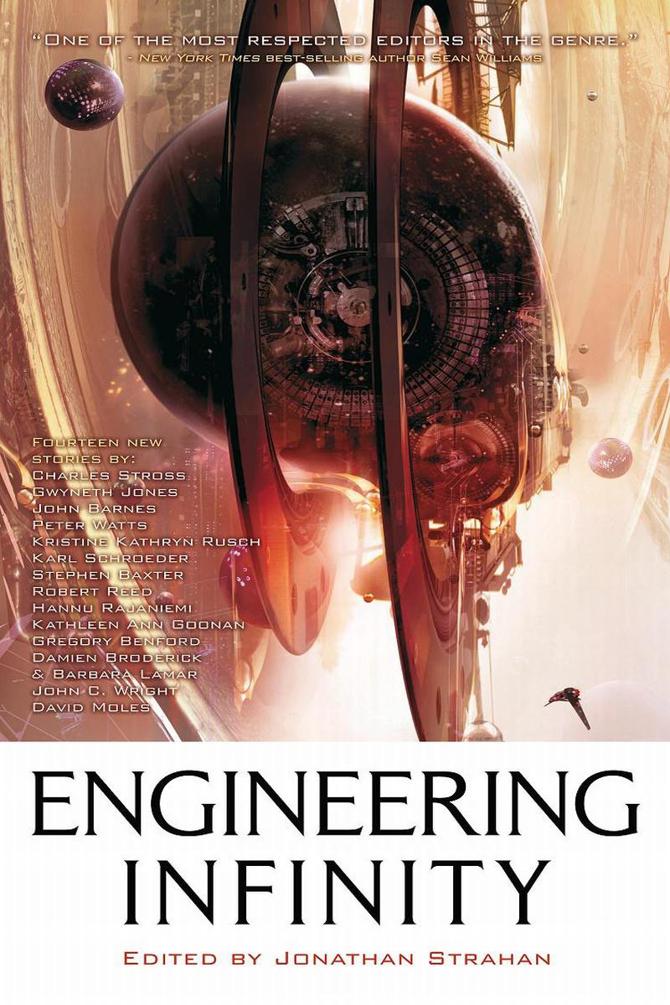

Engineering Infinity

Read Engineering Infinity Online

Authors: Jonathan Strahan

Engineering Infinity

Edited by Jonathan Strahan

In memory of Charles N. Brown and Robert

A. Heinlein, two giants of our field who each in his own way inspired my love

for science fiction.

“

Malak

” copyright © 2011 Peter Watts.

“

Watching the Music Dance

”

copyright © 2011 Kristine Kathryn Rusch.

“

Laika’s Ghost

” copyright ©

2011 Karl Schroeder.

“

The Invasion of Venus

”

copyright © 2011 Stephen Baxter.

“

The Server and the Dragon

”

copyright © 2011 Hannu Rajaniemi.

“

Bit Rot

” copyright © 2011 Charles

Stross.

“

Creatures with Wings

”

copyright © 2011 Kathleen Ann Goonan.

“

Walls of Flesh, Bars of Bone

”

copyright © 2011

Damien Broderick & Barbara Lamar.

“

Mantis

” copyright © 2011 Robert Reed.

“

Judgement Eve

” copyright ©

2011 John C. Wright.

“

A Soldier of the City

”

copyright © 2011 David Moles.

“

Mercies

” copyright © 2011 Abbenford

Associates.

“

The Ki-anna

” copyright © 2011

Gwyneth Jones.

“

The Birds and the Bees and the

Gasoline Trees

” copyright © 2011 John Barnes.

An anthology is not assembled by

one person, neatly and tidily, working in idyllic isolation (at least, not in

my experience). Rather it’s the incredibly fortunate outcome of the efforts of

a small village of talented and extremely generous people.

Engineering

Infinity

would not exist without the efforts of Jonathan Oliver and the

remarkable team at Solaris, my indefatigable agent Howard Morhaim and his

assistant Katie Menick, and the wonderful Stephan Martiniere who has done

another remarkable cover - I am grateful to them all. I am also grateful to

each and every one of the book’s contributors who have been far kinder and more

patient than I had any right to hope.

Finally, as always, I would like

to thank my wife Marianne and my daughters Jessica and Sophie, who allow me to

steal time from them to do books like this one. It’s a gift I try to repay

every day.

Beyond the

Gernsback Continuum...

Jonathan Strahan

I was in a bar. I think it was in

Calgary in Canada. And it was the middle of winter. Or it might have been the

bar in Denver in the United States, a little earlier in the same winter.

Wherever it was, it was the winter of 2008 somewhere in North America and

George Mann and the Solaris team had asked me to join them for a drink. I don’t

drink often and I don’t drink heavily, but I do drink at science fiction

conventions, especially when publishers have invited me to join them. It seemed

that Solaris would like me to edit an anthology, a hard science fiction

anthology or something similar, the book that has become the one you now hold

in your hands:

Engineering Infinity

. I was

flattered, delighted in fact, and given that I had some experience editing such

stuff, I agreed readily to the idea.

At the time, and in the several

months following that trip to Canada (it was Canada, I’m sure) we went back and

forth a little about titles and about which writers might be involved, but

oddly, in retrospect, what we didn’t discuss was what hard science fiction was,

or what it might be in the 21st Century. The reason for that, I think, is what

I now think of as the “Gernsback continuum.” Science fiction readers love

taxonomy - classifying, arranging and defining things - and what we love to

taxonomise the most is science fiction itself. The Gernsback continuum is the

slice of science fiction history that starts with Hugo Gernsback’s

Amazing Stories

, progresses to John W. Campbell’s

Astounding Magazine

and the Big Three of Science Fiction

(Robert Heinlein, Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke), and then on to the New

Wave and its descendants). It’s a mostly male worldview, a mostly white one,

and it holds at its heart “hard SF.”

The term “hard SF” or “hard

science fiction” was first coined in 1957 by P. Schuyler Miller to describe

science fiction stories that emphasize scientific detail or technical detail,

and where the story itself turns on a point of scientific accuracy from the

fields of physics, chemistry, biology, or astronomy, although engineering

stories were also commonly described as hard science fiction in the early days

of SF. The great early works of hard science fiction - James Blish’s

Surface Tension

, Hal Clements’

Mission

of Gravity

, Tom Godwin’s “The Cold Equations,” and Arthur C. Clarke’s

A Fall of Moondust

- are some of the best and most

enduring works of science fiction our field has seen. They all exemplify the

hard SF approach: emphasizing science content, linking it directly to the

narrative, and maintaining a rigorous approach to the science itself. They also

meet the most important requirement for the true hard SF story: they all are as

accurate and rigorous in their use of scientific knowledge at the time of

writing as was possible.

Hard science fiction has remained

a constant throughout the history of science fiction. In the 1950s it was where

the best tales of space exploration were forged; in the 1960s it was the heart

of near-Earth science fiction; in the 1980s it was the radical centre for the

British drive to the new space opera; and in the 1990s, with the arrival of

both quantum mechanics in science fiction and the singularity, it was the basis

for Kim Stanley Robinson’s meticulous and demanding

Mars

trilogy,

Greg Egan’s explorations of human consciousness, and Charles Stross’s

post-scarcity space operas.

This, however, is the 21st

century and I think things are becoming more complicated and complex. Science

fiction no longer subscribes readily to a single view of its own history. There’s

far more to our past than the Gernsback continuum, or indeed more recently the

Gibson continuum (the past and future history of cyberpunk), and science itself

seems to be an ever more wriggly and complex beast as we come to better

understand the universe in which we find ourselves. Frankly quantum mechanics

often sounds indistinguishable from magic. We’re also well into the Fourth

Generation of science fiction: the genre has been born, passed through

adolescence, into adulthood, and is moving into a post-scarcity period of

incredible richness and diversity. That impacts on everything in our field,

from the diversity of the people who write science fiction to whom and about

what they choose to write. We’ve also long since accepted that science fiction

writers aren’t back-room nostrodamusses reading tealeaves and predicting the

future. They’re people using science fiction as a tool to interrogate and

extrapolate from our present for what we can learn about the human condition.

All of this became increasingly

clear to me as

Engineering Infinity

came together.

Slowly drift set in, we moved away from pure hard SF to something a little

broader. Yes, each and every story here has at its heart a piece of scientific

speculation. Yes, there’s a real attempt not to break any known laws of

physics. But far more importantly, I think, the writers here who are some of

our finest dreamers turned away from Tom Godwin’s “The Cold Equations” and

towards the promise embedded in the title of this book itself: the point where

the practical application of science meets something without bound or end - our

sense of wonder. There’ll be times as you read the stories collected here -

encountering everything from a mirror that makes us ask who is real and who is

not to a cannibalistic zombie cyborg - when you might ask,

how

is this story hard SF?

My answer, the best answer I can give you, is

that some of the stories are classic hard SF, some are not. Some hold at their

heart a slightly anachronistic love of science fiction’s days gone by or simply

grab some aspect of science fiction and test it to destruction and beyond, but

all are striving to be great stories.

I should add,

Engineering Infinity

is not the last statement in an

evolutionary taxonomy of hard SF. For all that I’d love to see such a book, it’s

neither a definitive book of hard SF nor an attempt to coin a new radical hard

SF. Instead, it is part of the ongoing discussion about what science fiction is

in the 21st century. I hope you enjoy it as much as I have enjoyed compiling

it, and that maybe, just perhaps, it inspires you to look forward at what’s

coming next.

Jonathan Strahan

Perth, Western Australia

July 2010

Peter Watts

Peter Watts (

www.rifters.com

) is an uncomfortable hybrid of biologist and science-fiction

author, known for pioneering the technique of appending extensive technical

bibliographies onto his novels; this serves both to confer a veneer of

credibility and to cover his ass against nitpickers. Described by the

Globe

& Mail

as one of the best hard SF authors alive, his

debut novel (

Starfish

) was a

NY Times

Notable Book.

His most

recent (

Blindsight

) - a philosophical rumination on

the nature of consciousness which, despite an unhealthy focus on space

vampires, has become a required text in such diverse undergraduate courses as “The

Philosophy of Mind” and “Introduction to Neuropsychology” - made the final

ballot for a number of genre awards including the Hugo, winning exactly none of

them (although it has, for some reason, won multiple awards in Poland). This

may reflect a certain critical divide regarding Watts’ work in general; his

bipartite novel

?ehemoth

, for example, was praised

by

Publisher’s Weekly

as an “adrenaline-charged

fusion of Clarke’s

The Deep Range

and Gibson’s

Neuromancer”

and “a major addition to 21st-century hard SF,” while being

simultaneously decried by

Kirkus

as “utterly

repellent” and “horrific porn.” (Watts happily embraces the truth of both

views.)

His work has

been extensively translated, and both Watts and his cat have appeared in the

prestigious journal

Nature

. After a quiet couple of

years (he only published one story in 2009, although he managed to publish it

five times thanks to various Best-of-Year anthologies) a recent foray into

fanfic, and a more recent foray into the US judicial system, Watts is back at

work on

State of Grace

(the sidequel to

Blindsight

) and another project he’s not quite allowed to talk about just

yet. He does, however, feel a bit better about his life since winning the Hugo

in Melbourne for his 2009 novelette “The Island.”

“An ethically-infallible machine

ought not to be the goal. Our goal should be to design a machine that performs

better than humans do on the battlefield, particularly with respect to reducing

unlawful behaviour or war crimes.”

- Lin

et al

, 2008,

Autonomous Military

Robotics

:

Risk,

Ethics, and Design

“[Collateral] damage is not

unlawful so long as it is not excessive in light of the overall military

advantage anticipated from the attack.”

- US Department of

Defence, 2009

It is smart but not awake.

It would not recognize itself in

a mirror. It speaks no language that doesn’t involve electrons and logic gates;

it does not know what

Azrael

is, or that the word is

etched into its own fuselage. It understands, in some limited way, the meaning

of the colours that range across Tactical when it’s out on patrol - friendly

Green, neutral Blue, hostile Red - but it does not know what the perception of

colour

feels

like.

It never stops thinking, though.

Even now, locked into its roost with its armour stripped away and its control

systems exposed, it can’t help itself. It notes the changes being made to its

instruction set, estimates that running the extra code will slow its reflexes

by a mean of 430 milliseconds. It counts the biothermals gathered on all sides,

listens uncomprehending to the noises they emit -

--

-

hartsandmyndsmyfrendhartsandmynds

-

- rechecks threat-potential

metrics a dozen times a second, even though this location is secure and every

contact is Green.

This is not obsession or

paranoia. There is no dysfunction here. It’s just code.