Equilateral (4 page)

Authors: Ken Kalfus

He takes the far corner, as he always does, and Miss Keaton serves first, as usual and without ceremony. The ball sails past him before he can raise his paddle. He retrieves it and she fires it past him again. He returns the third serve, she puts it into the net, and the game begins in earnest.

Thayer and Miss Keaton rarely declare the score, for they keep close accounts of the game to themselves and there’s never a discrepancy. They play quickly, fully absorbed. The ball’s thumps against the table are followed by shallower taps as it rises up against the battledores, and in the adjacent offices the clerks look up, arrested by the characteristic, long-absent sounds of the game, relieved that Thayer is playing again. Miss Keaton

takes an early lead, forcing him into a defensive posture. His timing’s off.

Yet the game tightens and Miss Keaton feels a competitive heat rising within her. The heat is good, something is being ignited. She slams the ball hard into the opposite box, it flies obliquely to Thayer’s paddle, and then lands on her side, spinning. The triangle is completed and vanishes into unrecalled geometric space as the black sphere meets her paddle at another point, higher and to her right, drawing the initial line of another figure. Every angle generates its own sines and cosines, calculable relations described by long columns of unseen numbers. Thayer claws his way back to tie the game at seventeen. Moisture beads down her sternum. Before each serve they lock wide, unblinking eyes.

Miss Keaton thoroughly reviles herself when she falls behind on the next point. She will always despise losing, especially against Thayer, who considers himself the much superior player, but today’s match is staked. She desperately wants him to remain in camp. Ballard can ride out to see about the rock, if necessary. Yet at the moment Thayer pulls ahead, with the score so close and the decisive point so near, her sentiments flip. It’s a peculiar phenomenon, which she’s observed in herself before. She feels what he feels: the heat of his grip on the battledore, the pinch of his boots, even the lassitude after the fever against which he’s rebelling; she can see her shot approaching him as it barely clears the net and she wants what

he

wants—a point against her, a smash beyond her reach. She knows her empathy is foolishly placed, but the infinitesimal moment of weakness is enough to deflect her next return by a fraction of a degree, just

enough to overshoot the table. He presses the advantage and two serves later claims twenty.

“Yah-hah,” he says.

“Bugger.”

He laughs sharply.

She looks across the table into his cool blue eyes, which, she knows, have charmed women on four continents, not to mention more than one head of state. She detects a certain wateriness there. A gravely faithless notion flits past her, barely making itself known: the wish to see him return to London for proper medical care, the Equilateral be hanged.

Miss Keaton is about to speak, to urge him to reconsider the journey to mile 270, or at least to submit to a rematch, when they realize that another person has joined them inside the tent. They turn. It’s Bint. She stands at the tent flap, perfectly still. She’s a small girl, not yet fully grown, with plump lips, deep, wide-set eyes under thick brows, and a coarse Semitic nose. She’s been there for some time, against the unspoken command within the compound that Thayer and Miss Keaton shouldn’t be disturbed during a game. Perhaps she isn’t aware of the prohibition. She’s puzzled, pondering the meaning of the activity or performance or vital task that she has just witnessed. The secretary wonders if she recognizes it as a game, and whether there’s an analogous sport among the Arabs, and whether Arab adults even participate in friendly games and sport. Or does she suppose that this intense effort is somehow connected to the difficult labors being performed on the shifting, searing desert floor?

“Ping-Pong,” Thayer explains. “Table tennis.”

Bint apprehends the words through the fog of her native

language and tries to return them to him through the same miasma. They come out, “Bong-bong.” Miss Keaton detects a small secret shiver running through the girl’s delicate frame.

Δ

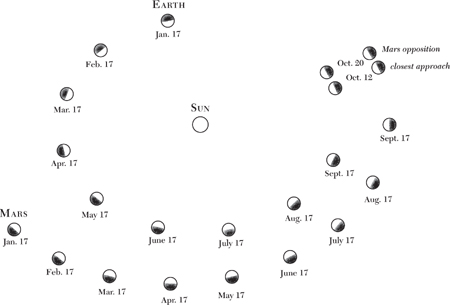

The letter from Hector France-Lanord, the chief astronomer at Meudon in the Paris suburbs, is accompanied by three fine sketches in his distinctive charcoal stipple. The French astronomer professes to have seen a new set of parallel shadow lines in Mare Australe, Mars’ dried southern seabed adjacent to the ice cap. As the two planets glide toward their closest approach, observers are straining to identify artifacts and natural land-forms on the surface that have developed since the previous pas de deux in 1892. The apparent, or observed, size of the planet’s disk, still only 6.5 seconds of arc, makes its surface features too small to be distinguished reliably, but Thayer and Miss Keaton, who respect Meudon’s equipment and France-Lanord’s eye, have been intrigued. In six months, on October 12, 1894, the planets will draw within less than forty million miles of each other; eight days later Mars will reach opposition, the moment when it lies directly opposite the Earth from the sun. The Martian disk will swell to 22 seconds and the southern hemisphere of the planet will be well placed for viewing.

Earth and Mars, 1894.

As Thayer fears, work has stopped at mile 270. Hundreds of fellahin idly mill in the heat. Some have laid out prayer mats, while others congregate near the water tanker as if it were a seaside refreshment stand. Their spades are sunk in the dirt like a line of pickets. The crates of dynamite brought by the blast crew molder in their wagons. The rock in question, an outcropping hardly fifty feet high, remains unmolested.

Thayer and his men are met by the manager of the blasting crew, a seven-fingered Romanian, or Vlach, who is said to have worked on the St. Gotthard Tunnel. He greets the expedition warmly, praising the miraculously fortunate alignment of stars that have brought them to this site. He inquires whether they would like to stay for dinner. When Thayer demands to know why the rock hasn’t been removed, the Romanian says the limestone is a small problem, hardly worth the professor’s attention. The rock ends about six hundred yards to the east. The most sensible course of action would be to excavate around it.

“No deviations,” Thayer declares, not for the first time.

From the moment the plans for the geometric figure were announced, they’ve come under assault from those who would

subvert them for the convenience of geography. As if the sides of the Equilateral were no more than railroad lines, engineers have proposed skirting outcroppings as well as sand dunes, ridges, gullies, and marshes wherever they encounter them. Thayer has to remind the engineers of the Equilateral’s purpose and fundamental principles. If the figure is forced to conform to the Egyptian landscape, the astronomers of Mars will be placed in the same difficult position as their colleagues on Earth: unable to convince parochial skeptics that the markings on the distant planetary surface are the work of sentient beings.

It’s the

disregard

of the natural landscape that proves man’s intelligence.

Thayer knew of course that there would be topographical obstructions, and for this reason an army of surveyors was mustered to position the Equilateral so that it would fall on the least possible number of them. Yet the foremen protest.

“The removal of this rock will begin within a quarter hour,” he declares. “Otherwise I will leave it to you to explain to the men why their pay has been docked.”

Thayer and his company, including Dr. McKinnon, remain at mile 270 until the first explosives are set off. Smoke and debris accompany the demolition, yet the force of each blast comes to him diminished, as if muffled by the sands or by the blanket of solar heat, which has gathered its noonday weight. But Thayer is satisfied that the rock is being removed. He gives the signal to return to Point A.

The Romanian, or Vlach (he’s actually an Albanian), watches the party leave, pleased with Thayer’s inspection. In his anger the astronomer again showed the determination and vigor on which

the project depends. News of his illness, which spread quickly among the fellahin up and down Side AC, enervated them and raised the specter of their abandonment in the desert. Thayer’s returning vitality will improve morale.

Δ

Thayer knows that mile 270 is only a single troublesome point on Side AC. Problems have appeared elsewhere. Ballard apparently had to knock heads together last week at mile 64, where a Bedouin work gang encountered some flooding along the marshy area near Nuweimisa. Now the engineer’s on his way to Point B, an excursion that will take the better part of a week. Thayer will have to send someone else, one of the junior engineers with a surveyor, to investigate a place on Side BC where two crews, one excavating in a northwesterly direction and the other southeasterly, failed to meet up.

But meanwhile progress has been made on this segment of Side AC, even since the morning. Riding along the side on a high-spirited Arabian, the best in Point A’s stables, Thayer peers into the broad trench, where for a mile out thousands of fellahin bow into their labors. Thousands more carry away the debris in hand-barrows. The excavators have been configured into a series of interlocking parallelograms, a geometric system Thayer devised to extract the soil with the greatest efficiency. This afternoon the lines of these figures have unfolded into new territory, extending the side.

The scrape of the spades is accompanied by the men’s singing, which ascends like smoke into the incandescent atmosphere. According to a French expert in primitive lyric, the compositions

are derived from fragments of existing indigenous airs and have largely replaced them throughout the territories of the Equilateral and beyond. The Equilateral’s songs are heard in coffeehouses from Rabat to Baghdad, their tunes strummed on zitherlike qanoons and pear-shaped ouds, or rapped out on darbukkahs. The men sing of their spades easing through the pliant sand and of sand less pliant, and also of their distant homes, as well as of lines and of angles, of triangles acute and obtuse, and of their secants and cosecants, and their rhymes also praise the golden section, in which a line is divided so that the smaller is to the larger as the larger is to the whole; the sagitta, the line that connects the midpoint of an arc to the midpoint of its chord; and the apothem, the line between the center of a polygon and one of its sides, and they give full-throated gratitude to the God who has decreed that the square of the hypotenuse is always equal to the sum of the squares of the sides, making possible the whole of trigonometry and then, lying beneath trigonometry, or around it and above it, the fundamental structure of reality.

Men pause in their labors as Thayer passes by. A few raise their arms; he presumes in salute. They know he has brought them here to win them glory.

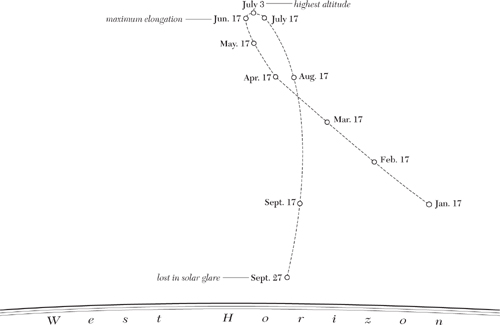

The Equilateral

will

be completed and the Flare

will

be ignited June the seventeenth, at one hour, fifty-two minutes, thirty-eight seconds Greenwich time, the instant that lines drawn from the sun to the Earth and from the Earth to Mars meet at a right angle. At that flawless Pythagorean moment, and only for that moment, a right triangle will blaze into existence deep within the heart of the Egyptian desert. The square of Mars’s distance from the sun will be equal to the sum of the squares of the distances between the Earth and the sun and the Earth and Mars. The angle at the Earth-Mars-Sun vertex will be 46.9 degrees, the maximum separation between the Earth and the sun as seen from Mars.

With the Concession’s funds exhausted, the fellahin will be sent back to their villages. In the autumn the world’s telescopes will be swung into position. In these months of painstaking scrutiny, while the Red Planet’s disk grows, man will confirm what canals and other artifacts have been constructed since the 1892 approach. Observing the dark blotches of vegetation that appear every Martian spring in the vicinity of the planet’s irrigation projects, terrestrial astronomers will count the victories their neighbors have won and the losses they have suffered in their struggle for survival. The astronomers will search too for some acknowledgment that the planet’s inhabitants have received the signal from Earth and are aware that intelligent beings share the solar system.