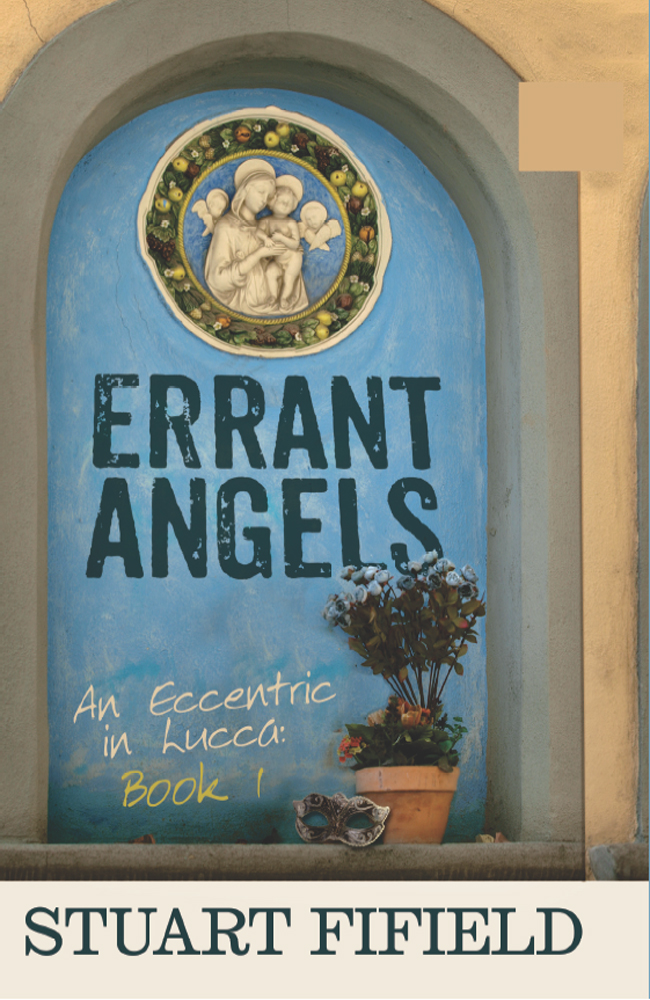

Errant Angels

Authors: Stuart Fifield

ERRANT ANGELS

By the same author:

Fatal Tears

, Book Guild Publishing, 2013

ERRANT ANGELS

An Eccentric in Lucca: Book 1

Stuart Fifield

Book Guild Publishing

Sussex, England

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by

The Book Guild Ltd

The Werks

45 Church Road

Hove, BN3 2BE

Copyright © Stuart Fifield 2013

The right of Stuart Fifield to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Except where actual historical events, locations or characters are being described for the storyline of this novel, all situations in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to living persons is purely coincidental.

Typesetting in Baskerville by

Norman Tilley Graphics Ltd, Northampton

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

A catalogue record for this book is available from

The British Library

ISBN 978 1 84624 970 9

ePub ISBN 978 1 90998 406 6

Mobi ISBN 978 1 90998 407 3

For DJH, who had the visionâ¦

Contents

1

âIt's getting late and it doesn't look as if she's coming!'

âThere's still plenty of time. I'm telling you that she'll be here. Thursday wouldn't be Thursday without a visit from theâ¦'

Their muttered conversation was interrupted by the arrival of yet another group of customers who, like all the others, stared covetously at the display of cakes. It was obvious that they were tourists; not that Gianni Canetti needed any further proof of this simple fact. The dazzling arrangement of delicate pastries, chocolate-dipped dainties and large cream-filled fruit creations displayed in the long, ornate, glass-fronted counter always produced the same effect on tourists. The locals had long ago accepted this mouth-watering Aladdin's cave of wonders as the norm, just like buying tomatoes or peppers at the market. For the army of tourists brought to this deliciously calorific heaven on the advice of all the leading guidebooks, the promise of a few moments of unrivalled pleasure on the taste buds produced a strange, glassy-eyed glaze, which quite literally stopped them in their tracks.

âHello, we areâ¦' said one of the group, intently studying a thick guidebook he held in both hands. It was opened at the section devoted to a vocabulary list. The man's sentence remained unfinished as he scanned the list of Italian words and useful phrases in his book. Gianni, who thought the man quite thick-set and unusually tall for an oriental, stood patiently behind the counter, a look of mild, amused

tolerance on his face, ââ¦visitors,' said the man eventually, a look of triumph on his face.

âUm humâ¦' replied Gianni softly, his smile unchanging.

Japanese? Or possibly Korean

, he reasoned.

The man was grinning and bowing slightly, which seemed to be part of the ritual of pronouncing the selected words from the guidebook.

âYou are visitors to Lucca?' cooed Gianni, grinning at them all in that natural, seductive, everyday way only successfully managed by Italian males.

While the visitor's smile remained fixed to his face his eyes betrayed the truth, which was that he had not understood much of what Gianni had said. He buried his nose in the guidebook once again, desperately trying to remember the sounds he had just heard and to match them to some phonetic translation in the list of phrases. He had not noticed that the rest of his group had abandoned him to his fate, spreading themselves out along the curved glass front of the counter, animatedly engaged in an intensive, yet subdued welter of indecision as to which pastry to select.

âI have only a little understanding,' replied the man with the guidebook, reading out the phonetic translation of the phrase he had found. He looked relieved.

Gianni smiled back warmly, but out of the corner of his eye he had noticed another smaller group, which was congregating outside on the pavement on

Via Fillungo

. They, too, would soon enter the cool atmospheric interior of the

Café Alma Arte

â most visitors to Lucca did â and that would cause a bottleneck at the counter. The café was an Art Nouveau jewel and was one of many such buildings lining

Via Fillungo

. But it had not been built to accommodate the army of tourists that the beginning of the twenty-first century had brought with it. More often than not, the busy little café was bursting at the seams. Confusion over the vocabulary in a guidebook definitely did not help the

free flow of customers in and out of the single, bevelled glass door.

âWould you like to speak English?' asked Gianni effortlessly, as he saw the next group about to enter from the pavement. In a perverse sort of way he quite enjoyed the struggle most tourists went through with their attempts to speak Italian â sometimes he found it difficult to control his mirth when what had been said in all good faith would have been enough to cause a diplomatic incident or send the visitor straight to the nearest confessional to do penance.

âHa⦠Yes, you speak English,' replied the visitor, who was only too pleased to close the guidebook and put it away. He turned to the rest of his group as he did so, gabbling happily in the knowledge that, for the time being at least his problems with the Italian language were over.

Of course I speak English

, thought Gianni, as he quickly and expertly placed the assorted order of dainties on individual white plates,

and so would you, if you had to deal with someone like the Contessa.

Behind him, his sister, Anna, was manipulating the Gaggia with similar dexterity, churning out all manner of coffee â

espresso

,

caffé Americano

,

latte

and

cappuccino

. In fact, the

Café Alma Arte

â the ânourishing gift' in a mixture of Latin and Italian â positively reeked of coffee. That was a large part of the café's attraction. There were those who said that they always had two cups for the price of one: the first being the inhaled luxury of over a century's accumulated coffee aroma that could be savoured before they imbibed the second one, the one for which they actually paid.

âI told you she's not coming,' repeated Anna, as she distributed the cups of steaming liquid amongst several small trays that lay on the serving shelf. âShe's usually been in and out by now. It's not like her to be this late. You know what the mad English are like; they have clockwork for souls!'

âShe'll be here. It is Thursday right up until we close,' replied Gianni, returning a large spatula to a basin of water and wiping his hands on his apron.

âPerhaps she's had a fall⦠At her age it is possible,' continued Anna, rolling her eyes in mock alarm as the Gaggia spat and fumed away.

âWhat dark thoughts you entertain,

sorella mia

,' muttered Gianni. âI hardly think the Contessa would be bothered by a fall. In any case,

if

anything had happened, all of Lucca would have heard of it by now. Have you heard of anything?' he asked, raising his eyebrows to emphasize the ridiculousness of her suggestion.

âAt her age she

would

be bothered by a fall,' replied Anna, her gaze firmly fixed on the chrome machine in front of her, âand you'd be lucky to hear

anything

above this racket,' she said, gesturing into the bowels of the café to where a capacity crowd was happily engaged in the twin delights of the palate and good conversation.

The consumption of the exquisite calorific creations and intoxicating coffees was almost a religious rite and the contented chatter in many tongues made the place sound like the United Nations. In fact, it was a bit like that august institution because any sense of international goodwill was only skin deep. The café's faithful but slightly belligerent locals were obliged to sit cheek-by-jowl with the tourists and were not about to give up their usual tables for anyone.

âAnd I have to tell you that the Gaggia has decided to play up ⦠again,' continued Anna, wiping down the front of the coffee-making machine with a damp cloth. The spout, through which scalding steam escaped to froth the milk, sputtered and occasionally spat angrily, allowing some of the leaking steam to condense on the front of the machine. The Gaggia was much older than either Gianni or Anna. Their father seemed to think that it had been there since Mussolini's time and there were many amongst the

cognoscenti

who claimed that the ancient build-up in its extensive network of pipes was partly the reason why the coffees it produced tasted so memorable. Over the intervening years, regular repairs and threats of replacement seemed to have kept it going. It might not be of quite the same vintage as the Contessa, but then again, she seemed ageless anyway.

âSomeone is going to have to look at it; the bloody thing's got a mind of its own at times,' continued Anna, slapping it with the wet cloth. âIt belongs in a museum.'

2

At the same time as the Gaggia was giving vent to its feelings in the café a delivery was being made further along

Via Fillungo

. Midway between

Café Alma Arte

and the old Roman amphitheatre stood

Casa dei Gioielli

, the âHouse of Jewels'. It was not a particularly large shop, but it was crammed to the gunwales with antiques. The exquisite items on display were of the utmost quality and none of them had a price ticket displayed. It was the kind of shop where customers knew exactly what they were looking for and did not concern themselves with the cost. Gregorio Marinetti, the much respected proprietor of this grand, if modest, emporium, stood looking at his latest acquisition.

â

Bellissimo

,' he purred in semi-ecstatic enjoyment of the object that stood on the tiled floor in front of him. For just a moment, standing in front of the age-clouded screen, he forgot the grim reality of his situation. In addition to being a well-known connoisseur of fine

objets d'art

, Gregorio Marinetti also harboured a recent secret, the alarming implications of which he had to fight very hard to keep in check. In the few minutes since the arrival of the screen, this secret had come to subconsciously terrify him. He had debts â very serious debts. Business had not been good of late and in a moment of desperation, he had turned to gambling to raise the much-needed finances. It had been a disastrous foray into something about which he knew absolutely nothing. In fact, his huge gambling debts had added to his problems alarmingly and his creditors â his

gambling âassociates', all of whom were unpleasant at the best of times â were becoming more and more aggressive due to his inability to settle.

âAre you certain that no one knows?' he whispered. The sound came out like a strangled wheeze. He tried again, taking care to take one or two calming breaths before he did so. âAre you certain that no one knows ⦠about the screen? Nobody can trace it ⦠back to me, I mean â¦' He cast a furtive glance over his shoulder and out through the shop window. He was also aware that he was sweating under the expensive cut of his business suit.

âAs certain as the Holy Father is a true Catholic,' muttered the smartly dressed man, irreverently. He stood behind Marinetti and spoke with a southern accent, which the antique dealer found hard to understand on certain syllables. Gregorio thought that this man probably came from Naples, or perhaps even further south.

âOf course nobody knows, otherwise we wouldn't last five seconds in this business now would we?' continued the smartly dressed visitor after a short pause. There was a lot of calm sarcasm in his voice and it was obvious that he did not tolerate foolish questions. âIn our business, we just

do.

We do not

explain.

'

He took a cigarette from his gold case and lit it. He didn't offer Marinetti one. As he replaced his lighter in his pocket, he turned his head and glanced casually out of the window. He wore an extremely well-cut suit that had probably cost twice what Marinetti's had. Despite the fine clothes, this man had a dangerous air of menace about him, but without any sign of nervousness. Why should there be? He was used to these sorts of deals; it was an important aspect of his profession. It was obvious to him from just looking at Marinetti's behaviour that

he

was the newcomer to dealing on the dark side of his profession.

âSoâ¦' said the man with the Naples accent, turning back

to Marinetti now that he had satisfied himself that everything was as it should be outside the shop. He exhaled a fine plume of smoke, ââ¦if you are satisfied, I believe that we agreed a sum ⦠if you please,' he said softly, gesturing towards the screen. Gregorio did not notice. Instead, he focussed perspiring eyes on the two associates his visitor had brought with him to carry the heavy screen into the shop in its protective wrappings. They now stood at the door, one on either side, like two nightclub bouncers. The antiques dealer shivered. These were large, well-built, muscle men under their Armani suits and looked decidedly unfriendly â even more so than the Neapolitan, who now stood waiting for payment of the agreed sum.

âYes⦠Yes, of course ⦠the sum agreedâ¦' repeated Marinetti, his baritone voice suddenly pitched unnaturally high. He coughed and his voice returned to something nearer its normal pitch. âIf I may, I would like to have a closer look.'

âIf you must,' replied his visitor, making a second irritated sweeping gesture towards the screen, as he shrugged indifferently. âBut I need hardly remind you that my time is extremely limited,' he continued ominously. Gregorio detected the hint of impatience in the man's voice, but as his nerves were severely on edge anyway, he put it down to his own over-active imagination.

The visitor turned and crossed the shop floor to where the other two men were standing. The three of them formed an inverted triangle pointing menacingly into Gregorio's usually placid and ordered world â a world which had started to fall to pieces. The antique dealer's palms were wet, as he expertly cast his gaze over every detail of the screen. It was Venetian, probably late fifteenth century and worth, at a conservative estimate, many times more than what he was going to pay for it. In his business, there were those silent collectors for whom the price of an

article they desired was of no consequence. Any illegalities simply disappeared into the anonymous and very isolated safety of their private collections.

âThere will be no questions?' asked Gregorio, a faint tremor in his voice; he wasn't sure if it was due to the excitement of being so close to a thing of such value or simple fear. He was still standing in front of the screen and had half-turned towards the door, dividing himself equally between the beautifully dingy object in front of him and the decidedly dodgy reality of his situation. The screen was going to be his salvation, but the human triangle at the door could yet prove to be his undoing. His visitor had almost finished his cigarette and shrugged, raising his eyebrows enquiringly in an unasked question. Gregorio raised his hand feebly towards the screen. âNo questions about the screen?' he repeated.

âHow many more times must I say this? I have already told you ⦠we do not answer questions,' replied his visitor softly, menacingly. âBesides, if I were to tell you anythingâ¦' he paused, placing one hand in his trouser pocket, ââ¦it would almost certainly be a lie. That is the nature of our business,' he concluded, a leer playing on his lips around the smouldering end of his cigarette. He had delivered the whole of the previous speech with the cigarette clamped delicately to his bottom lip. The ash had not even fallen from the end, so practiced was he in this manoeuvre. âYou have

that

, which is what you wanted,' he said, pointing to the screen with his free hand. âYou do not need to ask questions.'

Gregorio attempted a chuckle, but the noise that escaped from his throat sounded more like a phlegm-induced choke than an indication of mirth. His feet had started to sweat. He couldn't remember that happening since the day of his final

viva voce

examination at Pisa University, and that had been all of thirty years before. His nerves really

were

stretched and they had started to buzz.

âThe agreed sum?' repeated the visitor, as he plucked the butt end from his mouth, dropped it on the marble floor and ground it out with his shoe. It was a simple, smooth action, but one laced with warning menace. Marinetti suddenly felt an overwhelming urge to get this man and his two acolytes out of his shop before they polluted his environment any further.

âWe agreed the sum,' repeated Marinetti, casting a nervous glance out through the shop window.

Via Fillungo

seemed oddly deserted for the time of day. It was as if everyone knew that there was something less than legal going on in

Casa dei Gioielli

and had no wish to become involved. âPlease follow me to the office,' he continued, indicating the two doorways at the rear of the shop. One was his inner sanctum, the other was his stockroom.

Casa dei Gioielli

was, after all, of modest proportions and he couldn't put

all

of his treasures on display at the same time.

Twenty minutes later, the area of

Via Fillungo

outside Gregorio's shop was still almost empty â not that he noticed. He had paid for the screen in cash, which had all but wiped out his remaining cash reserves. Marinetti had let out a deep sigh as his three visitors eventually evaporated into the empty street. He hurriedly threw a large piece of brocade over the screen before anyone out in the street could get a good look at it. Then, as his lip curled up in disgust, he bent down to sweep the crushed butt end into a dust pan. Apart from the brooding presence of the screen, which remained standing in all its faded glory in the middle of the marble floor, the shop looked as it had done when he had opened it that morning. He fussed around, tidying and straightening his treasures. However, the brocade he had flung over the screen did not quite cover the face of the animal on the centre panel. The winged Lion of St Mark â the ancient symbol of the Venetian Republic â seemed to

glare at him from underneath the many layers of darkened varnish as it peeped around the hanging swag of fabric. From its position on the central panel of the screen, it seemed to know that its new owner had done something wrong. The noble beast resented being part of the dishonesty of the purchase. For the first time in his life, Gregorio Marinetti had involved himself in a seriously illegal transaction â something which, if it were ever to become common knowledge, would ruin not only his own, but also his family's long-standing reputation within the

Comune di Lucca.

His standing as a respectable antiques dealer would be in tatters.

âDesperate times call for desperate measures,' he hummed to himself nervously. All he needed now was the telephone call from his customer's agent to arrange collection of the screen and he could start to breathe easily again. âWhy doesn't the telephone ring?' he muttered. He found that with a little juggling, the words almost fitted the melody of â

Di Provenza il mar

', Germont's aria from Verdi's

La Traviata

. It was his party piece â one that the Contessa said he sang particularly well. The lion remained oblivious to this fact and the one eye that could see around the end of the brocade swag continued to follow Gregorio with a malevolent glare. âAnd let us be quite honest, they couldn't really get much more desperate than they are now.' He stopped suddenly and chuckled. It was no good; there were too many words to continue singing them to Verdi's famous melody. He felt far more relaxed now and, still chuckling, he straightened an ornate mirror and flicked at the gilded frame with his duster. He caught the reflection of the lion in the glass and turned around in surprise, to be met by the accusing glare. âYou have to take risks to restore the balance,' he muttered to the screen, âand when

you

are collected and paid for, the balance will be fully restored.' He promptly felt foolish for having spoken to an inanimate

object. He was on edge and his nerves were still a little raw. They were made even more so by the ringing of the telephone. Although expected, the sudden noise came as a shock and caused him to back into a seventeenth-century

escritoire

, its delicate legs scraping across the marble tiles.

âYes⦠Yes, I have it here⦠Oh⦠Is it not possible for you to collect it today? Forgive me, but I thought that that was the arrangement andâ¦' There was a note of worried dismay in his voice, as the caller cut across him. âBut of course, any time to suit the

signore

⦠Indeed, cash would be acceptable⦠Very well, until next Thursday then, when you will call to make final arrangements for the collection,' continued Marinetti, his mouth now quite dry, âif it cannot be beforeâ¦' he added somewhat pathetically, trying to disguise the anxiety in his voice. âPlease use my mobile; you have the number.' There was a curt mumble of acknowledgement on the line. âI think it is better that weâ¦' but the line had gone dead. As he replaced the handset, he realized that his client was the one who was used to giving orders â people who were that wealthy usually had no problem at all in making the world revolve around their particular needs and arrangements. Whilst still looking absently at the telephone, a new worry suddenly revealed itself to him. The simple fact was that this sudden change of plan had serious ramifications; he would have to find a safe place to hide the screen for a week. His feet were as wet as his mouth was bone dry. For a second, he looked up and stared straight ahead into his shop. The stark reality of the situation was that the

signore's

agent had delivered his client's message and had hung up. There would be no collection of the screen that day, or the next, or the day after. In fact, it would be a full week before he could get rid of the thing â as beautiful as it was â and solve his precarious financial situation. Once the screen had been collected Gregorio would have his money in untraceable cash, but having to

find a safe place to hide a stolen artwork for a week had not been part of the equation.

âYes, you will have to be hidden in the lock-up whether you like it or not!' he snapped at the lion, whose accusing glare scythed through the layers of darkened varnish like a surgical laser, until it fixed itself firmly on Marinetti. He crossed quickly to the screen and adjusted the piece of fabric until it hid the greater part of the lion's face and the accusing eye. Despite this absolving action, he still felt the eye boring into his conscience from under the cloth. The Lion of St Mark was displeased, even if, like Polonius, it had been concealed behind the arras.

Gregorio Marinetti felt a little calmer for not being stared at. Despite that, his feet were now so wet that they squelched in his expensive shoes as he walked across the marble tiles of his shop towards the inner sanctum.