Escape from Wolfhaven Castle (4 page)

Read Escape from Wolfhaven Castle Online

Authors: Kate Forsyth

When everyone was seated, the trumpets sounded again and a small party of grand strangers swept in. They were greeted by the steward and shown to chairs at the high table.

Lord Wolfgang stood. ‘Lord Mortlake, welcome to

Wolfhaven Castle. We hope you have a pleasant stay with us, and enjoy our feast.’

The leader of the strangers inclined his iron-grey head and smiled. He was a handsome man, with dark eyes and an eagle nose. Sebastian stared at him with interest, knowing he was the Lord of Frostwick Castle, in the cold, mountainous lands to the north. Sebastian’s mother always said they bred them tough up there, and indeed Lord Mortlake seemed strong and stern.

The witch stood up, and the room fell silent. She raised high her silver goblet. ‘Merry midsummer to you all!’ she cried.

Everyone cheered and clashed their cups and goblets together. Then the feast began. Sebastian was not permitted to eat until all the nobles at the high table had finished, and so he rushed to carve the roast boar, and pour goblets of mead.

Lord Wolfgang and Lord Mortlake were discussing trade routes. Mistress Mauldred was instructing Lady Elanor how to eat her food like a lady. Elanor looked as if she had something to say to her father but had no

idea how to interrupt him.

Sebastian wished he could sit down at the servants’ table, where everyone was singing and laughing and eating with gusto, tossing titbits to the dogs under the tables. They looked like they were having fun. Except for the pot-boy, who was most inappropriately making faces at Lady Elanor, as if urging her to do something. Sebastian frowned at him, but then Lord Mortlake clicked his fingers for more mead, and Sebastian hurried forward with the bottle.

‘I’m sorry, my daughter is far too young to be thinking of marriage,’ Lord Wolfgang said. ‘Besides, I hope that she will, in time, marry for love, as I did.’

‘Of course,’ Lord Mortlake said, though he looked as if something disgusting had been shoved under his nose. ‘But my dear son Cedric is already quite taken with your pretty daughter, and I’m sure she shall find him most pleasant company.’

The dear son Cedric was shovelling food into his mouth as fast as he could, splashing gravy all over his shirt. It was a mystery where he put it all, for he was the skinniest kid Sebastian had ever seen. Lord Mortlake

elbowed his son, and Cedric looked up. ‘What?’ he said, his mouth full of roast boar.

‘Weren’t you saying before how very pretty you think Lady Elanor is?’ his father prompted.

Cedric looked aghast. He glanced at Elanor, who sat bolt upright, her brow knotted with anxiety. ‘Err … umm … yes. Very … umm … nice.’

‘Perhaps after dinner you two could walk in the garden together,’ Lord Mortlake said.

‘My daughter is only twelve,’ Lord Wolfgang said. ‘Far too young to be thinking about such things. Besides, they are kin. Such talk is unseemly!’

‘They don’t need to be married now,’ Lord Mortlake said. ‘But it’s always wise to plan for the future, don’t you agree, my dear Lord Wolfgang? Let’s take the dowry into account. Your daughter is, of course, more priceless than rubies. But we would be happy to settle for the rights to use the river and the harbour.’

‘We have spoken about this before,’ Lord Wolfgang said. ‘My father revoked your father’s rights to use the Wolfhaven River because he refused to pay the

tolls and taxes. Then your father burned down the harbour-master’s house and half the town.’

‘Ah, ancient history,’ Lord Mortlake said, waving his pheasant leg. The huge ring on his right hand flashed red. ‘Let bygones be bygones.’

‘Well, then, what of the issue of piracy?’ Lord Wolfgang said. ‘Men from your land keep raiding our river-boats and stealing all our cargo.’

‘No! Really? I fear you must be mistaken, my lord. Thieves and bandits are everywhere, I admit, but I am sure those river-pirates you speak of do not come from my land. We have no river, remember.’

‘I’m afraid I will not discuss the matter of rights to use

my

river until I’ve been compensated for all

my

losses,’ Lord Wolfgang said. ‘And I certainly will not discuss my daughter’s marriage! Not for another ten years!’

Elanor smiled gratefully at her father, but Lord Wolfgang did not notice.

Lord Mortlake grimaced and crushed a walnut shell to powder in his hand.

The servants cleared away the platters of gnawed

bones and brought out jellies and meringues and crystallised violets. More mead was poured at the high table, while another barrel of pear cider was rolled out for the lower tables.

When everyone’s lips and fingers were shiny with sugar, the Grand Teller rose and went to stand before the fireplace at the head of the hall. Its carved stone mantel arched far above her head, displaying two massive keys crossed one over the other. Sebastian knew that they were the keys to the war gate, only opened when the castle was under attack. One key was black and the other white, and both were longer and thicker than his arm.

‘It is time for the midsummer tale,’ Arwen said. A murmur of anticipation rose, and she waited till all was quiet again.

‘Long, long ago, enemies came over the waves to Wolfhaven Castle, with lightning in their hands and darkness in their souls. The people of the land were filled with terror. It seemed as if all must die. Four great heroes arose, seizing weapons made of flame and wind and stone and sea …’

Sebastian forgot how hungry and tired and sore he was, and listened, enraptured. That witch sure knew how to tell a good story. The story was filled with perilous quests and mighty battles and fearsome beasts. At times the Grand Teller’s whole body changed, growing and swaying as if she herself was a snake, or shrinking and crouching as if she was a tiny mouse, her voice nothing but a frightened squeak. Once she flung her arms wide, and for an instant the shadows of huge wings wavered over the stone walls.

‘Back to back, the heroes stood, fighting with the last strength left in their arms.’ Arwen thrust and feinted with an imaginary sword, her face set as hard as any warrior facing death. ‘But as they hacked and hewed at the mighty beast, the spatters of its shattered body rose up into fearsome life again, a dozen, ten dozen, a hundred, a thousand, ten thousand more …’ Arwen’s voice quickened and grew shrill. She raised her arms. Sebastian forgot to breathe.

The Grand Teller did not speak for a long moment. Her hands dropped. The great hall was utterly silent. Arwen leant forward. Very quietly, she said, ‘Then,

with a mighty roar, the dragon at last answered the call and swooped through the cavern, his flaming breath blasting that multitude of ravenous beasts into nothing more than a swirl of ashes and smoke.’

Her hands circled, her arms snaking out. The candle flames guttered, smoke eddying through the air.

‘Our heroes fell to their knees. They laughed. They wept. And so the land was saved.’

A great sigh rose from the audience.

Arwen dropped her hands from her face and looked about the great hall. ‘They say the four heroes still sleep, somewhere under our very feet, in the hollow mountain beneath the castle. One day, when Wolfhaven Castle has need of them, they shall wake and fight to save us once more.

‘By bone, over stone, through flame, out of ice, with breath, to banish death,’ she intoned. ‘One day the sleeping warriors will arise again.’

Then she folded her hands and bowed her head low. Applause echoed around the hall. People sitting at the lower tables stamped their feet and banged their tankards together. Sebastian quickly gathered himself

and hurried to fill the goblets of the lord and guests so they too could drink a toast to the witch. He noticed that Tom was staring at Lady Elanor again, grimacing and jerking his head to one side. Lady Elanor looked anxious. Sebastian felt his ears turn hot and red. That pot-boy needed a lesson in how to behave respectfully towards his betters!

Lord Mortlake did not drink, but only clenched his hand about his goblet as if trying to crush that to powder too. When at last the applause died down, he rose to his feet and clapped his hands sharply.

Silence fell. Everyone turned to stare at him. He showed his teeth in a smile.

‘A charming story, quite charming. A little predictable, perhaps, but I suppose that’s the way of those cobwebby old tales.’ He smiled at the Grand Teller, who did not smile back.

‘Now, to the next order of business,’ Lord Mortlake went on. ‘As a sign of our deep affection for Lady Elanor, we have prepared a special dish for her. Bring it in at once!’ He clapped his hands again and his squires ran outside. They returned a few minutes later, pushing

a trolley. On the trolley was the most enormous pie Sebastian had ever seen. His stomach rumbled loudly. Luckily, the wooden wheels of the trolley made such a racket on the flagstones that nobody noticed.

Lord Mortlake drew his sword with a flourish. Everyone gasped and leaned back in alarm, but the Lord of Frostwick Castle simply used the sword to cut open the pie. Out flew a flock of white-winged doves that swooped up into the rafters.

Coo-coo

, they cried.

Coo-coo.

One flew right over Cedric’s head and, in its fright, dropped a great white splat of droppings into his hair. Cedric shrieked and began rubbing at his head with a napkin. Lady Elanor hid her smile as best she could. Mistress Mauldred hissed: ‘Ladies do not giggle!’

To everyone’s amazement, a boy leapt out of the pie and somersaulted down to land before the high table. He then went tumbling and cartwheeling all around the room, so fast he was practically a blur. He ended with a high, double backflip, landing neatly on his feet.

‘Jack Spry, at your service, Lady Elanor,’ he cried,

snatching off his velvet hat and bowing low. Everyone cheered and clapped.

Then the boy sang, sweet as any lark:

‘

Jack be nimble,

Jack be quick,

Jack jump over the candlestick.

Jack be nimble,

Jack be spry,

Jack jumps out of the apple pie!

’

He was thin, about eleven years of age, with a mop of black curls and sparkling black eyes. He was dressed in a short tunic made of yellow and orange squares, with striped leggings below. On his feet were boots dyed the same vivid orange. Elanor said gravely, ‘Thank you, Master Spry.’

The boy bowed again.

‘Jack Spry is our gift to you, to be your fool and keep you entertained,’ Lord Mortlake said. ‘He can sing and dance and tell jokes and do tricks, and is a fine acrobat.’

Jack Spry did another backflip, landing squarely on his feet. Everyone clapped and cheered, and he

bowed to the crowd. Lord Mortlake flipped him a coin and it disappeared as if by magic.

‘Let this be the beginning of a new friendship between our houses,’ Lord Mortlake said to Lord Wolfgang, smiling broadly.

Lord Wolfgang looked troubled. ‘We thank you for your kind consideration,’ he answered. ‘But—’

‘So, will you give us the river rights?’ Lord Mortlake interrupted.

Lord Wolfgang answered, ‘I am always willing to discuss terms, you know that, my lord. But this is not the time or the place. It is time for our midsummer bonfire. I hope you will join us for the dancing.’

He rose and held out his arm for his daughter, who rose too. They led the way out of the great hall, the other nobles streaming behind them, laughing and chattering.

Sebastian grabbed a platter of uneaten food and rushed with it to the antechamber, where he and the other squires would quickly gobble down what they could before they had to go to the garden to serve the nobles.

From the corner of his eye, he saw a flash of yellow and orange. Curious, he looked out the door to see Jack Spry, with his boots in his hand, hurrying up the stairs to the Lord’s Tower.

S

parks from the bonfire flew up into the starry sky. The castle bell tolled twelve times. It was midnight, and time for Arwen the Grand Teller to read the tell-stones.

Hands shaking with excitement, Quinn walked slowly towards the bonfire, where the Grand Teller stood, waiting. The dancers stopped whirling and gathered close. Lord Wolfgang and his painfully proper daughter sat on their chairs under the oak tree. Lady Elanor’s governess stood behind her, one hand weighing on her shoulder. She wore a huge red ring which seemed to make her hand even heavier.

The Lord of Frostwick Castle stood some distance

away, watching with a curiosity that seemed tinged with mockery. His son stood at the banqueting table, gobbling down honey cakes.

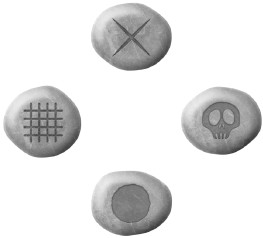

Quinn knelt before the Grand Teller and gave her the bag of tell-stones. Arwen poured the small white pebbles out on a cloth spread under the birch tree, its branches hung with golden ribbons and yellow witcher’s herb.

Arwen then drew four tell-stones at once, placing the first to the north, the second to the west, the third to the south and the final stone to the east. Quinn knew that each direction of the compass represented a different element—Earth, Water, Fire and Air—and so had a different meaning.