Eureka Street: A Novel of Ireland Like No Other (7 page)

Read Eureka Street: A Novel of Ireland Like No Other Online

Authors: Robert Mclaim Wilson

`Got a light'

An old woman stood over his seat, her damp coat trailing off her shoulders. She brandished her breasts at him.

'Mmmm?' asked Chuckie.

'A light. Got one?'

Chuckie, who rarely smoked, always carried a lighter. It was meant to grease the wheels of conversation with foxy, darkhaired girls in bars. He fumbled in his pockets and passed the cheap, disposable thing to the old woman. She lit her cigarette and made to hand it back to him.

'No, you keep it,' said Chuckie.'I've given up'

The old woman paused with her hand held out in an exaggerated posture of surprise. `Ach, God love you, son. That's very decent of you.'

She lurched back to her seat. Chuckie could see her sitting four rows forward in the no-smoking section, telling her companion - an equally corpulent, equally decrepit his largesse. The exclamations of surprise were audible through most of the bus and Chuckie had to suffer a complicated series of nods and smiles from the old women, who had both turned round to favour him with their acknowledgements of his beam geste. Some of the other passengers also turned and there were some quiet smiles at his expense. Chuckie blushed and worried.

He tried to stare through the wet windows. The fields and houses drooped in the aquatic exterior. He was glad to be abus in such weather. As he looked around the vehicle, he could not repress a sensation of cosiness, as though this Ulsterbus with its condensation, its body heat and smells was some kind of biosphere that sustained them all. He would almost miss it when he was rich.

When Chuckie got home, his mother was in the kitchen making smells he didn't like. He heard her call out some greeting. Without answering, he went upstairs to his bedroom. There he exchanged his wet apparel for dry. Then he sat on his bed and combed his thin wet hair.

Chuckie slept in the larger bedroom that faced onto the street. His mother had made it so years before, so long ago that he had forgotten his gratitude and her sacrifice for a decade or more. His window was open and, after a few minutes, he could hear his mother's voice from the open street. She was standing on the doorstep swapping talk with the other matrons of Eureka Street. It felt like all the evenings he had ever known. Sitting in his eight-foot bedroom, listening to his mother talk, her head six foot from his feet. The houses were tiny. The street small. The microscale of the place in which he lived gave it a grandeur he could not ignore.

In Eureka Street the people rattled against each other like matches in a box but there was a sociability, a warmth in that. Especially on evenings like this, when the sun was late to dip. When finally it did dip, there was an achromatic half-hour, when the air was free from colour and the women concluded their gossip, the husbands came home and the children were coaxed indoors from their darkening play.

He put down his comb and looked out of the window. Mrs Causton had come across the road from the open doorway of Her husband was still working and her kids weren't young so she had twenty minutes to talk away until her old man came home. His mother had known Caroline Causton for forty years or more. They had been at school together. As Chuckie looked down on them talk, with bent heads and folded arms, he couldn't help feeling something close to sorrow for his mother.

Chuckie's mother was a big woman, built historical, like a ship or a city. He found it hard to picture her as a girl. But something in the quality of the light or his mood, some insipidness in the air, suddenly helped him to strip the aggregate of flesh and years from both women and he glimpsed, briefly, a remnant of what they had been. As always, he wondered what she had dreamt. He resolved that he would stop being ashamed of his mother.

Chuckie had been ashamed of his mother ever since he could remember. Shame was, perhaps, the wrong word. His mother provoked a constant low-level anxiety in him. Inexplicably, he had feared the something he could not name that she might do. Since he had been fourteen years old, Chuckie had lived in quiet dread of his mother making her mark.

Sometimes, he would comfort himself with thoughts of her incontrovertible mediocrity. She was just an archetypal working-class Protestant Belfast mother. Not an inch of her headscarf nor a fibre of the slippers in which she shopped departed from what would have been expected. She had doppelganners all along Eureka Street and in all the other baleful streets around Sandy Row. It was absurd. He spent too many hours, too many years, awaiting the calamitous unforeseen. Nothing could be feared from a woman of such spectacular mundanity.

Nevertheless, she worried him.

For ten years, Chuckie had dealt with his unease most undutifully. After his father had left home and Chuckie was faced with the prospect of living with his mother, he decided simply to avoid her as best he could. And he did. There had been a decade's worth of agile avoidance. He couldn't remember when they had last had a conversation of more than a minute's duration. It was a miracle in a house as tiny as the one they shared. The sitting room, kitchen and bathroom were the flashpoints in this long campaign. She was always leaving little notes around the house. He would read these missives. Slat called at six. He'll meet you in the Crown. Your cousin's coming home at the weekend. He told her almost all the things he needed to tell her by telephone. Sometimes he would leave the house just so that he could find a phone box and call her from there. Sometimes it felt like Rommel and Montgomery in the desert. Sometimes it felt much worse than that.

Caroline Causton looked up and saw him at his bedroom window He did not flinch.

`What are you up to, Chuckie?' quizzed Caroline.

`Nice evening.' Chuckie smiled. His mother, too, was looking at him now. She couldn't remember when she had last seen her son's face split with a smile of such warmth.

`Are you all right, son?'

`I was just listening to you talk,' explained Chuckie gently. The two women exchanged looks.

`It reminded me of when I was a kid,' he went on. His voice was quiet. But it was an easy matter to talk thus on that dwarf street with their faces only a few feet from his own.

`When I was a kid and you sent me to bed I would sit under the window and listen to you two talk just as you're talking now When the Troubles started you did it every night. You'd stand and whisper about bombs and soldiers and what the Catholics would do. I could hear. I haven't been as happy since. I liked the Troubles. They were like television.'

As Chuckie's mother listened to those words, her face fell and fell again and, as Chuckle finished, she was speechless. She clutched her hand to her heart and staggered.

'Shall I call him an ambulance?' asked Caroline.

Chuckie laughed a healthy laugh and disappeared from the window.

Caroline faced his mother.'Peggy, what's got into your boy?'

But Peggy was thinking about what her son had said. She remembered that frightened time well but his memory seemed more vivid, more powerful than her own. She remembered soldiers on the television and on the streets. She remembered parts of her city she'd never seen being made suddenly famous. She remembered the men's big talk of resistance and of civil war, of finally wiping the Catholics off the cloth of the country. Chuckle remembered pressing his head against the wall underneath his bedroom window and the whispers of his mother and her friend. For the first time, she glimpsed how beautiful it might have seemed to him.

Caroline was unmoved. `Is he on drugs?'

Chuckle's mother smiled her friend away and went indoors. She found her son in the kitchen. She had to catch her breath when she saw that he was happily cooking the meal that she had begun.

'Nearly ready,' said Chuckie.

An hour later, telling his mother he wanted to do some work on a job application (she was still unused to the heady sensation of such a ball-by-ball commentary), Chuckie went upstairs to his bedroom.

There he opened the little desk he'd used, or mostly not used, when he was a schoolboy. He took out a sheet of paper, an old pencil and his school calculator, a massive thing, unused for a dozen years. He switched it on and was amazed to find it still worked. The omen was propitious.

Before he wrote anything he looked around the tiny room. He felt a lump in his throat at the thought that he had slept almost every night of his long life in this tiny room. The walls bore the marks of old posters ripped and replaced as his passions had formed and formed again; footballers, rock stars, footballers again, and then beautiful big-hipped girls in their underwear. These were the signs of his growth as surely as if someone had marked his height on the wall as he grew.

He looked at the picture of Pope and self above the little desk. It was one of the few photographs of himself that Chuckie possessed. He was young in that photograph. He was not so fat but neither was he an oil painting. Actually, thought Chuckie smiling, in that photograph that's exactly what he was.

He took the photograph/painting from the wall and slipped it into a desk drawer. That was then and this was now. He composed himself, drew breath, looked round one more moist-eyed time and started to write.

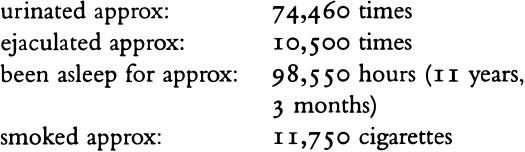

It had been more difficult than he might have imagined. He judged that he should not count the past week and should only tot up the totals until his thirtieth birthday since that was the day that he had made all his big decisions. Most of it was, by its nature, imprecise and he had spent much time hazarding estimates. However, he was confident about most of them.

He wrote his list. This is what his list said:

On my thirtieth birthday

I had

walked approx: sustained an erection for approx:

grown approx: had sex approx: earned approx:

3 2,000 meals

17, 5 20 litres of liquid (approx: 8,ooo of which contained alcohol)

20,440 miles

186,150 mins, 3,102.5 hrs, I29.27 days

5.40 metres of hair 175 times

no fucking money

He tacked the paper to the wall where his Pope photograph had been and sat back. It pleased him to think that he had been asleep for so long. That was exactly how it had felt as he considered the waste of his past life. He felt that he had always been sleeping. But it was not a depressing statistic. If you took a sanguine view, it meant that he was still young: it meant that he was really only eighteen years old.

He smiled to think how much and how long he'd pissed. His bladder was famously weak and it had been, perhaps, pressed into more work than it deserved. Some fastidiousness had prevented him from calculating his defecation rate.That was something he hadn't wanted to know.

The aggregate of his copulations depressed him. Though the total duration of his life's waking erections was fairly impressive, he hadn't had anywhere near enough sex. It was only 12.5 times per year since he was sixteen. There'd been enough girls - they just hadn't hung around for long. Max would change all that. He didn't know anything about couldn't even claim her he had a feeling that she would improve his averages.

He was going to telephone her now, he decided. It would wait no longer. Despite the new rapprochement with his mother, he didn't want her listening in. He decided he would sneak out to the phone box on Sandy Row. Leaving the sheet tacked where it which his mother would marvel while he was went downstairs.