Europe in the Looking Glass (6 page)

Read Europe in the Looking Glass Online

Authors: Robert Byron Jan Morris

BOLOGNA IS A LARGE MANUFACTURING TOWN

containing 280,000 inhabitants. Famous in the Middle Ages for her resistance to papal encroachment, she has retained this independence of attitude with regard to the puritan elements of Fascismo. In Florence, but a fortnight before our arrival, an American woman had been brought into court for kissing in the street, and had only with difficulty been rescued by her consul from a term of imprisonment. In Bologna there is no need to kiss in the street. Whether or not it is due to the combined excesses of a barracks and a university, the town is famed as a seminary of temptation, a fount of loose-living, whence tributaries flow into all the other cities of Italy. Oddly enough, however, the inhabitants are never in bed. At one in the morning the cafés are as full as at midday. At two, they close. At four they re-open. This is in extreme contrast to most Italian cities, which invariably present, after midnight, an empty and subdued appearance.

But the main feature of Bologna is her arcades. Not only the streets in the centre of the town, but the side streets and the slum streets, are all arcaded. The fronts of the houses rest on every imaginable kind of arch, pillar and capital, Gothic and Classic. Thus it is possible to walk always in the shade and always under cover. The effect is one of strong shadows and bright arcs of light; while at night the pale glimmer of the street lamps flits in long streaks up the everlasting corridors, thick with the undispersed heat of the molten August day. And everywhere the echoes resound as in a huge subdued swimming-bath, to heighten the chatter and hubbub of the

cafés, and accentuate the solitary footstep of an errant girl, or the bang of a door and the rattle of a chain.

Though the opinions of others on the subject of hotels are tedious, the Baglioni deserves record as in our opinion the best in Italy. The food, which made no cosmopolitan pretences, showed to what heights Italian food could rise. The staff were attentive and polite, and the management offered to change our English cheques when the banks were shut. Finally our bill was not excessive. The building had been once an old palace, and the frescoed vaulting of the dining-room was still intact. This had been the work of one of the brothers Caracci, natives of the city, executed in that same late Roman style of design adopted by Raphael in the famous loggia at the Vatican.

We ourselves were lodged in an annexe, also a former palace, with a staircase of grandiose proportions adorned with white and gold urns and rams’ heads. At the top was a frescoed ceiling representing some scion of the eighteenth century nobility borne aloft by attendant Graces – many of whom were also burdened with his various armorials. This staircase gave us a private entrance to another street, which, though we were not supposed to know of it, enabled us to forestall the dawn without waking the night-porter. On one occasion, however, the key was lost, the porter to all intents and purposes drugged, and David was obliged to shout Simon and myself awake through a fourth floor window – to the surprise of the neighbouring inhabitants. It was only a vivid dream that he was being murdered in the gutter beneath by the Fascisti that induced me to go to the door and rush quite unnecessarily into the street in my pyjamas. We shared our staircase with the local branch of the Maritime Bank and a number of other residents, whom we used to frighten by prowling up and down it on tiptoe, until the cashiers began to think that they were the victims of a plot.

Next door but one was the Fascist Lodge, where meals were served to the members in an open courtyard. On the pavement of the arcade outside was inlaid the axe of the organization,

surrounded by a wreath of laurel leaves. Thither we – or rather David and myself – had gone with our friend the

night-watchman

, to be enrolled; but it was unfortunately a necessary condition of membership that we should be permanent residents of Bologna. Though at times we began to think that this eventuality must be fulfilled, we never gave up hope of avoiding it. From our bedroom windows we could watch the activities of the local organization. One day three lorry loads of boys arrived back from a camping expedition. They seemed in high spirits. Fascismo is in fact a sort of boy scout regime; but instead of staves it carries revolvers. Italy is the victim not so much of a dictatorship, but of an ochlocracy, the rule of an armed mob, and an immature mob at that. Some slight account of the higher ideals of the party will be found in the last chapter but two.

The days passed in various ways. An up-to-date shop in the main square provided us with English books and papers. It also stocked the life of Henry Ford, translated into Italian. I read a number of the plays of Shaw. That a technique so completely inartistic, that these bare anatomical views of human nature, the bones of which are dried and classified, not always correctly, for the sole purpose of expressing the once rather shocking philosophy of the author, should have received such unanimous acclaim at the hands of the past generation, is an instructive commentary on the Edwardian struggle against Victorian hypocrisy. The antithesis, of course, is to be found in Chekov, whose edifices do not show their girders. For some reason, however, he is frequently described by the London Press as ‘the Russian Shaw’. By the same process of thought we have always regarded EI Greco as ‘the Spanish Millais’.

As we sat about the cafés of the town we made various friends. I discovered Simon one afternoon talking unconcernedly in English to a man who could speak not a word of any language but Italian. He appeared to be a retired engine-driver living on twenty-five lire a day, who would be pleased to start work again if we could get him a job in England. Providence momentarily

loosed my tongue to dilate on the prevalence of unemployment in that country, but I was cut short by his remarking that he knew some ladies whom he particularly wanted us to meet that evening. Simon also picked up with an Egyptian commercial traveller in cotton, who wore a red fez. He was much impressed by our acquaintanceship with a former ornament of Balliol College, Oxford, a countryman of his, whose brain after the Gordon legend, is said to be the greatest thing that Egypt has produced of late years. For Bologna, he seemed strangely ignorant of the whereabouts of the other sex. On the other hand, David, sitting by himself in a café, was suddenly joined by one of the Bersaglieri, who spoke a kind of

lingua franca.

At first they chatted, discussed barrack life and the origin of the cock’s feathers that adorned his hat. He then announced that David must meet a certain lady – with her mother – whom he was entertaining tomorrow, Sunday evening. What the presence of the mother portended, David was unable to fathom.

One of the first things that we had noticed upon our arrival in the town was the quantity of posters on the hoardings displaying in large capitals the words

ALBA

V

BOLOGNA

Upon close inspection this legend, dated for Sunday, August 16th, resolved itself into an announcement for the Cup Final of all Italy. We ordered the hotel to procure us the best seats that were to be had, and were drinking vermouth prior to setting out for the field in the Via Toscana, when the

engine-driver

, whom we had re-encountered, hailed a friend of his. The friend was going to the match also. He refused a drink, but stood in a statuesque pose until we had finished ours. He then accompanied us. A party of four, we stepped into a taxi and joined the Derby Day crowd that was streaming out of the town to the scene of the match.

‘Alba v. Bologna’. The affect of those three words upon the Latin temperament can scarcely be exaggerated. Imagine all the football crowds and Cup Final crowds that the world has ever seen; the queues outside the Ring; the downs at Epsom; the stands at Aintree. Multiply the checks, friz the hair, impressionize the neckwear and point the tan and chocolate brogues; accelerate the voices and the movements; cover the whole with a cloud of dust; and that will convey some impression of the voluble multitude with whom we pushed through the gates and into the stands. The field itself was small and, where there were no stands, surrounded by palings over which peeped tin advertisements and villa residences of red brick. For some reason it was marked out as for hockey.

The sun, now half-way down the heavens, seemed to suck away the little air that was left. Five o’clock arrived. The two teams ran sportingly on to the field at a gymnastic double, the captains of each bearing bouquets of tuberoses and pink carnations. The home team was champion of the north, and her captain had skippered Italy’s international team last year. Alba was a Roman team, champion of the south. As the opposing sides lined up, the spectators became almost silent, so great was the tension. Then the ball was kicked off and the shouting began. We found ourselves seated in the midst of the Roman contingent, who were endeavouring, not unsuccessfully, to pit their lungs against the combined voices of Bologna’s thousands. Later they began to take exception to the methods of the northerners, and a fight ensued two rows behind, which was stopped by the police.

The referee, a very plump man, received a good deal of abuse. But all minor excitements were drowned in the ear-splitting enthusiasm that greeted the first goal, shot by the Bologna captain after twenty minutes’ hard play. His team fell about his neck and kissed him – an unpleasant spectacle in view of the physical conditions resulting from exertion in the extreme heat.

Half-time found the score 1–0 in Bologna’s favour. Alba, at the beginning of the second half, showed more dash, and began

to press. In the last quarter of an hour, however, the side went completely to pieces and eventually lost by five goals to none. The players showed no ability to dribble, though at difficult kicks, and at heading the ball, they were unusually apt. Any attempt at a barge evoked volleys of protest, and was invariably given as a foul. At every opportunity the crowd shouted ‘

OFF

SIDE!’ and ‘’ANDS’. The winners, we were glad to think, had been trained by an Englishman.

After it was over, it was utterly impossible to find a taxi. The trams were invisible beneath the struggling humanity that clung to their outsides like swarms of bees. And we had walked half-way back before we found a cab. We returned to the hotel and washed. Then we went to dine at a small restaurant, embowered with oleanders, recommended by our companion, who paid for the dinner. The conversation was in French.

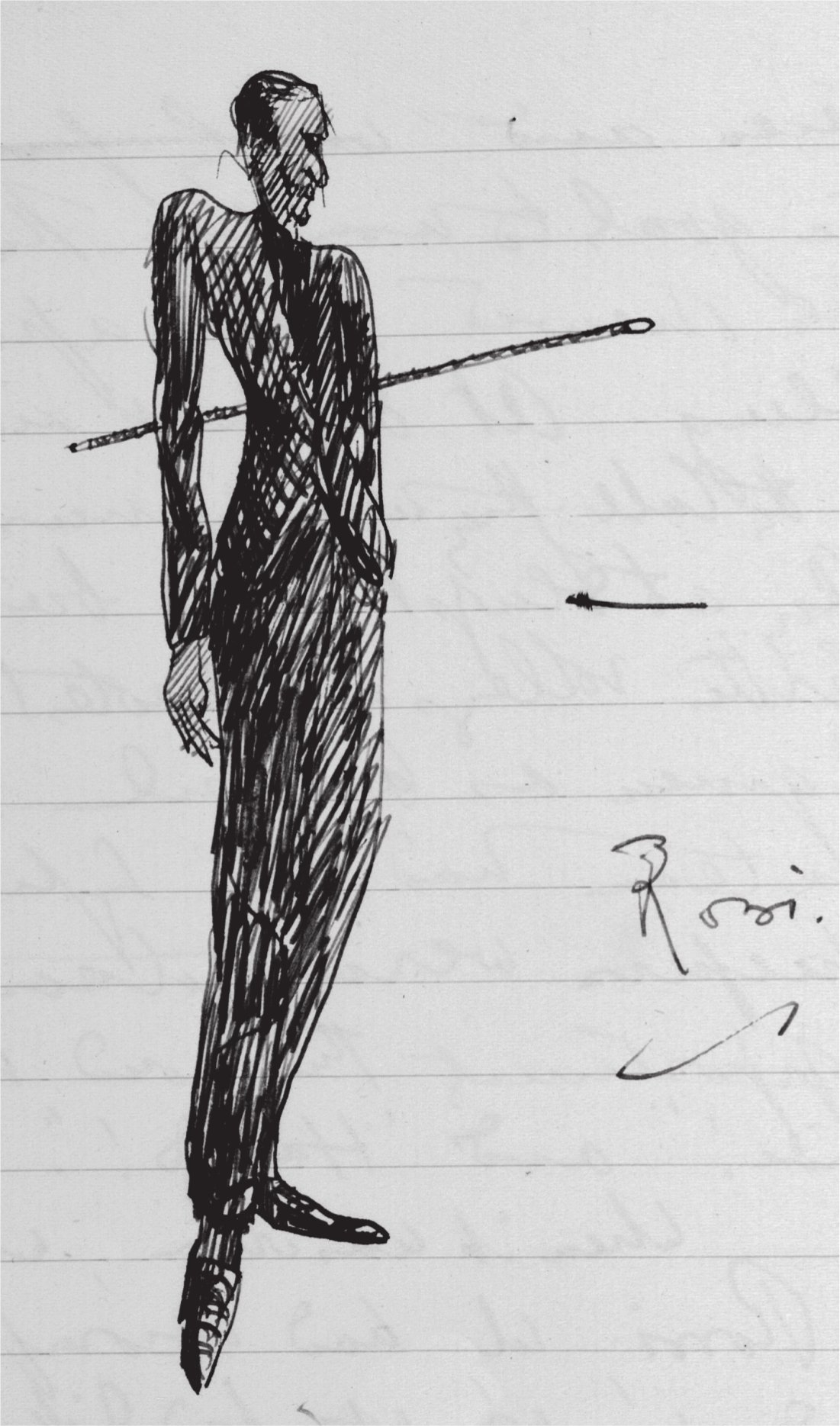

Our new friend belonged to that familiar type who live on their wits, and whose conversation, though containing a sub-stratum of truth, is embellished with the fiction necessary to their own glorification and the making of a good story. His name was Alfredo Rossi, and he produced a visiting card belonging to his brother, who was apparently a commercial chemist engaged in the artificial manure trade. In appearance he was thinly made and bony, standing about six foot one in height. His lips were slightly pursed, the upper lip forming a point in the middle, which rested on the lower. Sinister, staring eyes moved inquisitively about beneath his hanging brows. His face was dark, golden brown, and his hair was black. His long body was clothed entirely in black; black shirt, black tie, black handkerchief, black suit, and black buttoned boots. His garments clung. In manner he was most friendly.

During the war he had fought on the Italian front and learned to hate the French, having been at one time liaison officer where one line ended and the other began. His particular company had been dependent on the French commissariat and as a result had almost starved. We were told later, that in Rome, after the war, the waiters refused to serve French people in the restaurants, so hated were they. This feeling has not disappeared.

On demobilisation, Rossi had joined d’Annunzio at Fiume. Then, when that venture had been brought to its end, he had become one of the first Fascisti, in the days when Fascisti were openly murdered in the streets, and had fought, dislodged and drowned in the moat the communists who had obtained possession of the castle at Ferrara. He now represented himself as Chief of the Ferrara Fascisti. Money flowed from his pockets. He regretted, however, that he was unable to keep a mistress as well as a wife. In the same breath he said that he would show us round the town on the morning of the morrow; and in the afternoon, if the car was still delaying us, would we come out and see Ferrara with him, where he hinted vaguely at a country house.

He arrived on Monday, as he said he would, at ten o’clock. I was the only one dressed or even awake. His arm linked in mine, we set out together, talking halting French. He displayed the genuine love of good buildings and historical association that is innate in nearly all Italians. First we visited the old university. The walls were frescoed from wainscoat to ceiling with the heraldic bearings of former professors and distinguished students; amongst them were the names of several Englishmen. Over a door was a bust of Cardinal Mezzofanti, who received Metternich on one of his northern Italian tours and spoke forty-two languages with fluency. We were shown, also, the room fitted with carved stalls and a sort of canopied throne at one end, in which human dissection was first practised, with a papal inquisitor looking through a hole in the wall, and Mass being celebrated underneath. Some students, studying law, regarded us aghast. Napoleon, during

his short rule, had considered the old buildings inadequate and transformed them into a library, moving the seat of learning to others more capacious – an isolated example of the beneficial thoroughness which characterised his administrations. Thence we walked to a theatre, designed in the form of a horseshoe with splayed ends by Bibiena, and decorated in green and gold. This is one of the few eighteenth century theatres still intact. In general appearance, its balustradings are bolder and rather earlier than the delicate gold filigree work that covers the inside of the Fenice Theatre, at Venice. The morning finished with the picture gallery, containing a depressing collection of the less interesting

seicento

masters, and, as David remarked, more square feet of Guido Reni than all the rest of the world put together.