Eva (2 page)

“Hanna!” he cried. He did not recognize his own voice. “Take over. I’ve been hit.”

He glanced out the window. A haze blurred his vision as the blood drained from him and the shock began to dull his senses. Less than fifty feet below lay the battered, burning ruins of Berlin—a city crumbling in the agony of its death throes. Through the debris-strewn streets, running like open scars between the gutted, battle-scorched buildings, little black figures scurried aimlessly. Russians?

Wehrmacht?

Refugees? No matter. They all looked like frenzied ants in an anthill, raked over and put to the torch. His mind was numbed. He had not realized the totality of destruction.

He felt the woman, crouched in a half-standing position behind him in the single-seater plane, reach across him and grab the controls from his hands. A red haze closed in—and

Luftwaffe General

Ritter von Greim lost consciousness.

Flying at roof-top level the Storch dipped and recovered sharply as

Flugkapitän

Hanna Reitsch fought the controls from her awkward position behind the comatose man. She felt his head flopping insensibly between her outstretched arms. She willed herself to ignore it. In lightning-fast succession her flying stunts through her years as a test pilot raced through her mind: the near fatal crashes; the first jet planes; flying the live V-1 aerial bomb. But nothing like this.

She could reach only part of the controls. She stretched her slight five-feet-two frame as far forward as she could. She clenched her jaw in angry determination. She would make it. Hitler had summoned them. On a vital matter. He needed them. And she would not let her Führer down.

She looked out. She had to get her bearings. They had left Flughafen Gatow on the far bank of the Havel River west of the Chancellery only a few minutes earlier, beginning their sixteen-kilometer flight to the center of Berlin. They had crossed the river and the crater-dotted expanse of Grunewald Forest. On her left, to the north, through the reddish haze of smoke and dust she could make out the proud, imposing structures of the Olympia Stadion. She peered down at the gutted and scorched buildings just below. She knew where she was. Over the Charlottenburg district—better than halfway to the makeshift landing strip on the East-West Axis beyond the Victory Monument.

Suddenly the little single-engine monoplane shuddered and banked as shrapnel or bullets from below slammed into a wing. The starboard wingtip brushed a tall ruin as Hanna struggled to right the craft. Dammit! she thought viciously. Another four, five kilometers. Dammit! Not now! Not after flying all the way from Munich to Rechlin Luftwaffe Base in Mecklenburg, 150 kilometers northwest of Berlin, and from there to Gatow—with half their twenty-plane fighter escort shot down during the flight. Not after finding the Storch at Gatow Airfield—the only plane they could possibly hope to fly in to the beleaguered Chancellery—and taking off under enemy artillery fire. She would not be shot down.

Not now!

She threw a quick glance at the damaged wing. Gasoline was pouring from the wing tank.

Two more kilometers.

The firing from below had stopped. She passed over the Tiergarten—the Berlin Zoo. She banked, lined up the plane with the Charlottenburg Parkway, and came to a lurching, bumpy landing just before the Brandenburg Gate.

A dust-streaked military Volkswagen careened toward the plane. A lighter colored, dirt-free circle on the sloping hood between the frog-eye headlights bore witness to the fact that the spare tire had recently been removed. The canvas of the convertible top usually gathered behind the rear seat was missing, leaving the naked metal struts folded up like the legs of a dead spider.

The little vehicle skidded to a halt next to the Storch. A young SS officer was standing next to the driver, holding on to the windshield. He gave a smart

Heil Hitler

salute.

“

Obersturmführer Knebel, zu Befehl!”

he snapped. “At your orders!”

Hanna leaned from the cockpit. “The General has been hit,” she called. “Help me get him down.” She uncoiled herself from her cramped position, ignoring her protesting muscles.

Greim had regained consciousness. His face was chalky and drawn. He winced as they wormed him from the cockpit. His foot dripped blood.

“I have a staff car waiting for the General,” the young SS officer said. “Over there.” He pointed. “I am to—”

“Forget it,” Hanna interrupted him. “Just help me get him into the Volkswagen. Now! I want to get him to the Bunker Lazaret at once.”

The driver piloted his little Volkswagen along the shell-pitted, debris-strewn Unter den Linden, making as much speed as he could. The young

SS Obersturmführer

stood beside him, clinging to the windshield, peering ahead, calling directions and warning him about obstacles. In the rear seat sat Ritter von Greim, rigid in pain, scrunched into a corner, as Hanna tried to cushion his injured foot against the bumps and lurchings of the vehicle.

Shocked, appalled, they stared at the destruction around them. As far as they could see a suffocating shroud of dirty gray dust and smoke hung over the city, splotched with reddish fire balls from burning buildings, licked by blood-red fingers of flame reaching into the darkened sky.

Their progress was slow through the ravaged avenue, strewn with the cracked and splintered trunks of the once proud and famous linden trees, snapped like bones on a torture rack, littered with toppled lampposts and the wrecks of abandoned, burned-out cars. They drove past the scorched and gutted buildings, pockmarked by shrapnel, their blackened, empty windows watching the little Volkswagen’s journey through this forecourt of hell. And playing an ominous obbligato to the infernal phantasmagoria, the awesome sounds of distant battle, the shelling, the rockets, the artillery fire and the wails of fire engines and ambulances—from time to time blotted out by ground-shaking explosions.

They turned into the nearly deserted Wilhelmstrasse, past the once-splendrous Adlon Hotel, most of it still standing, battle-scarred and fire-scorched. The once great thoroughfare—center of government offices—was filled with rubble, shattered glass, and broken masonry from the demolished buildings; only a narrow lane remained open through the wreckage. Muddy water, burst from broken mains, flowed past the piles of debris, swirling in mini-maelstroms where partly clogged drains or cracks in the pavement led to the sewers below.

The driver threaded the vehicle precariously between one such whirlpool and a blackened half-track, still burning. In the oily pool floated a disemboweled dog, slowly circling in the eddying water, rhythmically dipping into the vortex and resurfacing—too big to go down through the drain.

Bleakly Greim looked at the devastation around him. Defeat lay over the mortally wounded city like a blanket over a corpse. He knew he was witnessing the end of a great metropolis. The death spasms of the vaunted Third Reich. Like that wretched dog, he thought dismally. Dead, but not willing to go down.

They jolted past the badly damaged, long since abandoned Old Chancellery Buildings, a huge bomb crater blasted out in front of it, filled with ash-coated water slowly swirling as it bled into the subterranean cavities below, and past Goebbel’s Propaganda Ministry, its blackened façade echoing its purpose—poised across from one another like a doomed Scylla and Charybdis.

Skirting a disabled Jagdpanzer they turned the corner into Vossstrasse. The New Chancellery directly on their right was still standing, but air raids had blasted gaping holes in the walls. And makeshift barricades had been erected at the imposing entrance.

Grimly they stared at the ravaged buildings where deep in the bowels of the earth below the bleak ruins lay the Führer Bunker of Adolf Hitler. From the roof above, pointing toward the heavens, as if in accusation, the haughty flagpole stood naked, stripped of the Führer’s personal standard with its steel and flames and its swastika—the

Hagenkreutz

—set in a field of arabesques, which always flew over the Chancellery when Adolf Hitler was in residence.

Idly Greim wondered if the naked pole was an attempt to fool the enemy air raiders into thinking that the Führer was elsewhere, or to prevent the suffering Berliners from storming the place, demanding relief. Or was it simply an oversight?

The Volkswagen came to a halt.

General Ritter von Greim and

Flugkapitän

Hanna Reitsch had arrived at the Bunker.

The hospital bunker deep under the complex, connected to the even deeper Führer Bunker through a series of underground passages, was teeming with activity. It was a little before 1900 hours. Ritter von Greim was lying on a stretcher while a doctor was attending to his wounded foot. Hanna stood by his side.

Suddenly a familiar, raspy voice spoke behind them.

“

Mein lieber

Greim!

Gnädiges Fräulein

Hanna!”

In the doorway to the Lazaret stood Adolf Hitler.

They both turned toward him.

Hanna was shocked. Her beloved Führer had changed, aged alarmingly since last she saw him. In a birdlike stoop he stood smiling at them. His complexion was unhealthily sallow with a chalky appearance, his cheeks sunken. His hair had turned gray; making his distinguished little mustache, which she found so attractive, look darker than ever in his pallid, waxen face. But his deep-set eyes still burned with the familiar fire. His right hand clutched his left before him in a vain effort to check its constant trembling, a reminder of the assassination attempt at the Rastenburg Wolf’s Lair in July of the year before, when a bomb had demolished the conference room in the Lagebarrack. She felt the pressure of a deep sadness build in her chest. The Führer. Adolf Hitler. The greatest man Germany had ever produced, having sacrificed himself for his beloved fatherland, was as much a ruin as was the city in which he had chosen to make his gallant last stand.

In a hunched shuffle, dragging his left foot, Hitler moved over to Greim. He beamed down at him.

“Miracles can still happen,

mein lieber

Greim,” he rasped. “You and

Fräulein

Hanna are here.” He looked at them. His eyes suddenly flashed in rage. “

Reichsmarschall

Goering has betrayed me!” he shouted. “Deserted the Fatherland! The coward made contact with the enemy behind my back and I have given orders for his immediate arrest!”

He stared down at Greim, lying mesmerized on the stretcher.

“I hereby name you, Ritter von Greim, the

Reichsmarschall’s

successor,” he intoned solemnly. “Commander in chief of the

Luftwaffe

with the rank of

Feldmarschall!”

His eyes bored into them. “Nothing is spared me,” he said hoarsely. “Nothing! Disillusionment. Betrayal. Treachery. Heaped upon me. I have had Goering stripped of all his offices. Expelled him from every party organization.” His voice rose steadily as the fury built in him. “He is a traitor! A deserter! I have been betrayed by my generals. Every possible wrong has been inflicted upon me. And now this! Sold out by my oldest comrade!”

Abruptly he stopped. Neither Greim nor Hanna said a word. Hitler turned to the doctor.

“I want the

Feldmarschall

moved to the Führer Bunker,” he ordered curtly. “I want

Standartenführer

Stumpfegger to perform any necessary surgery personally. I want the

Feldmarschall

fit and able to fly out of here in four days!”

He turned on his heel and left the Lazaret.

Even under thirty feet of earth and sixteen feet of concrete the bunker had trembled and shaken when later that night the Russian heavy artillery units for the first time since the onslaught on the city had hurled their explosive shells to strike the Chancellery itself. Until now only aerial bombs from enemy aircraft had been able to reach the heart of Germany—the place Hanna Reitsch reverently looked upon as the Altar of the Fatherland. The Führer Bunker.

But now the Russian hordes were only a few kilometers away.

Adolf Hitler sat at his desk alone in his study, under the oval painting of Frederick the Great, the Prussian warrior king who was his idol. It was the only wall decoration in his bunker study. It was painted by Anton Graff. Hitler had bought it in Munich in 1934 and it had been with him ever since. It had become a fetish. A symbol of his own greatness. Now a thin film of cement dust that had sifted down during the bombardment dulled the surface of the oil painting.

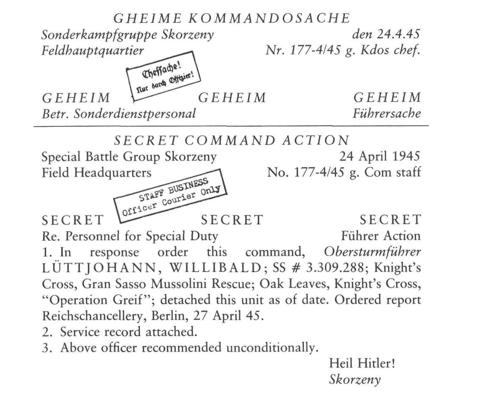

He could not sleep. It was dawn, Friday, April the 27th. No one in the bunker knew what kind of day it was above. During the night, elements of the U.S. 3rd Army had crossed the Danube, outflanking the city of Regensburg. The vital channel seaport of Bremen had been taken by divisions of the British 2nd Army, and the Baltic port of Stettin had fallen to Marshal Rokossovsky’s 2nd White Russian Army. But Hitler had no thoughts for these defeats. Only for the paper he held in his trembling hands.

The message.

The message from

Standartenführer

Otto Skorzeny.

Absentmindedly he brushed the thin covering of cement dust off his desk. Once again he read the message, brought to the bunker only hours before by an SS officer courier: