Every Grain of Rice: Simple Chinese Home Cooking (14 page)

Read Every Grain of Rice: Simple Chinese Home Cooking Online

Authors: Fuchsia Dunlop

Tags: #Cooking, #Regional & Ethnic, #Chinese

Until recently, meat was considered a luxury in China. Most people ate it only rarely, as the longed-for relish that added richness and flavor to a diet based on grains and vegetables. Only at the Chinese New Year—when every rural household slaughtered a pig and feasted on its meat throughout the holiday— was flesh at the center of the Chinese dinner table. I remember one man telling me that in the bitter years of the 1960s and 1970s, when even grain was scarce, he would use a single slice of belly pork to wipe his hot wok and lend his vegetables some of its savor, before putting it away to use another time; others have told me that they had tantalizing dreams about meat.

Even in times of plenty, moderation in diet has traditionally been seen as a sign of good character in China, and images of the

tao tie

, a mythological beast that is thought to represent the vice of gluttony, have served as a warning against self-indulgence. The epitome of the evil ruler in China is the last king of the ancient Shang Dynasty, who not only hosted orgies, but entertained his guests with a “lake of wine and a forest of meat.” In contrast, the sage Confucius showed his self-restraint in a fastidious approach to food and drink, refusing to eat food that had not been properly cut or cooked and not allowing himself to eat more meat than rice.

Although in recent decades, with rising living standards and the advent of factory farming, meat has become cheaper and more widely available, many people, especially in the countryside, still live mainly on rice or noodles, with plenty of vegetables and tofu and small amounts of delicious meat. It’s the kind of dietary system recommended more and more by those around the world who are concerned about the environmental consequences of factory farming and the effects on the body of eating too much grain-fed, intensively reared flesh.

The Chinese food system lends itself readily to the frugal use of meat. Most ingredients are cut into small pieces so they can be cooked quickly and eaten with chopsticks. As little as half a chicken breast or a couple of slices of bacon, stir-fried with vegetables, can be shared by a whole family, while a potful of red-braised pork or a whole fish, served alongside a few vegetable dishes, is enough meat for a group. (The idea of serving an entire steak or sea bass for each person is unthinkable in traditional Chinese terms.) Tofu, cooked with mouthwatering seasonings, is a rich source of protein, while the use of preserved vegetables and fermented sauces gives largely vegetarian ingredients the tempting savory tastes associated with meat.

For the ethnic Han majority in China, “meat” means pork unless otherwise stated. Lamb and mutton are sometimes eaten in the north, with its proximity to nomadic pasturelands, and are strongly associated with the Muslim and Mongolian minorities. In the south they are traditionally disdained for their “muttony taste” and generally eaten infrequently. Beef plays a minor role in traditional Chinese cooking: in the past oxen were primarily regarded as beasts of burden and there were periodic bans on their slaughter for meat. Other kinds of flesh—including goat, rabbit, venison and other game—are eaten in some regions and on some occasions.

Pork, the mainstay of Chinese meat cooking, is eaten fresh, brined, smoked, salt-cured and, in some areas, pickled. And, frankly, I don’t know anyone who does pork better than the Chinese, with their marvellous hams and bacons, their sumptuous roasts and slow braises, and their skilful use of just a little meat to bring magic to a whole potful of vegetables.

The recipes that follow, which include some of the most delicious Chinese meat dishes I know, are designed to be eaten with vegetable dishes as part of a Chinese meal. A dish of twice-cooked pork uses a relatively small amount of meat and will feed four or more people when served with other dishes. Red-braised pork or beef will go further if you add vegetables or tofu to the pot. Lamb may be used as a substitute for beef in some recipes, and either lamb, beef or chicken for pork, especially in stir-fries (Muslim restaurants in China usually serve beef or mutton versions of classic pork dishes). But whatever meat you choose, I recommend putting the expense into quality rather than quantity and buying the best you can afford.

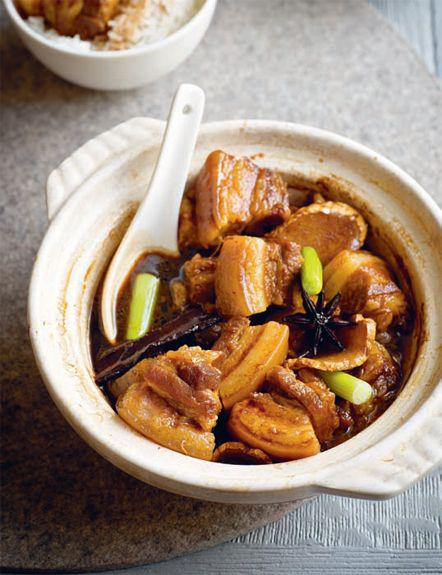

RED-BRAISED PORK

HONG SHAO ROU

紅燒肉

Red-braised pork may be one of the most common of all Chinese dishes, but it is also one of the most glorious, a slow stew of belly pork with seasonings that may include sugar, soy sauce, Shaoxing wine and spices. Every region seems to have its own version: this is my favorite, based on recipes I’ve gathered in eastern China. If my experience is anything to go by, you won’t have any leftovers. My guests tend to finish every last morsel and usually end up scraping the pot. If your guests are more restrained, leftover red- braised pork keeps very well for a few days in the refrigerator and a good spoonful makes a wonderful topping for a bowl of noodles (tap

here

). I don’t recommend freezing it, however, as this ruins the delicate texture of the fat.

This recipe will serve four to six as part of a Chinese meal. To make it go further, add more stock or water and a vegetarian ingredient that will soak up the sauce most deliciously. Puffy, deep-fried tofu is a fine addition to red-braised pork, as are hard-boiled eggs, dried tofu “bamboo” and the little knotted strips of dried tofu skin that can be found in some Chinese supermarkets (the latter two should first be soaked in hot water until supple). In rural households in China, they often add dried vegetables such as string beans and bamboo shoots, which should also be pre-soaked. You can also use root vegetables such as potato, taro or carrot, or peeled water chestnuts: just make sure you cook the vegetables with the pork for long enough to absorb its flavors, and adjust the seasoning as necessary.

To reduce the amount of oil in the final dish, make it in advance and refrigerate overnight. Then scrape off the layer of fat on the surface and keep it in the refrigerator to add to your stir-fried mushrooms or other vegetables. If you prefer a less fatty cut, pork ribs or shoulder are also magnificent red-braised. And you can, if you like, cook the pork slowly in an oven instead of on the burner—not very Chinese, but often more convenient (for this, preheat the oven to 300°F/150°C/gas mark 2).

1¼ lb (500g) boneless pork belly, with skin, or shoulder

2 tbsp cooking oil

4 slices of unpeeled ginger

1 spring onion, white part only, crushed slightly

2 tbsp Shaoxing wine

2 cups plus 2 tbsp (500ml) chicken stock or water, plus more if needed

1 star anise

Small piece of cassia bark or cinnamon stick

Dash of dark soy sauce

2 tbsp sugar

Salt, to taste

A few lengths of spring onion greens, to garnish

Cut the pork into ¾–1 in (2–3cm) chunks.

Pour the oil into a seasoned wok over a high flame, followed by the ginger and spring onion and stir-fry until you can smell their aromas. Add the pork and stir-fry for a couple of minutes more. Splash in the Shaoxing wine. Add the stock, spices, soy sauce, sugar and 1 tsp salt. Mix well, then transfer to a clay pot or a saucepan with a lid.

Bring to a boil, then cover and simmer over a very low flame for at least 1½ hours, preferably two or three. Keep an eye on the pot to make sure it does not boil dry; add a little more stock or hot water if necessary. Adjust the seasoning and add the spring onion greens just before serving.

TWICE-COOKED PORK

HUI GUO ROU

回鍋肉

This simple, hearty supper dish is one of the best-loved and most delicious in Sichuanese cuisine. I remember once interviewing three top Chengdu chefs for a magazine article, and each of them independently told me that of all the culinary riches Sichuan had to offer, this was their favorite dish. There is something about the rich, fragrant meat, cooked in a sizzle of intensely flavored seasonings and set off by the garlicky freshness of the leeks, that is utterly irresistible. It’s the perfect accompaniment to a bowl of plain steamed rice.

The name

hui guo rou

literally means “back-in-the-pot” meat, because the pork is first boiled, then stir-fried.

It must be allowed to cool completely before you embark on the final dish: if you try to slice it warm, the layers of fat and lean meat will separate. Recently, I’ve taken to buying a large piece of belly pork from a really good butcher, boiling it, leaving it to cool and slicing. I then freeze the slices in thin layers, in twice-cooked pork-sized portions. The frozen slices can be cooked, which means that I’m never more than about 15 minutes away from a plateful of twice-cooked pork, a very happy state.

7 oz (200g) boneless pork belly, with skin

6 baby leeks, trimmed (or Chinese leaf garlic)

2 tbsp cooking oil or lard

1 tbsp Sichuan chilli bean paste

1 tsp sweet fermented sauce

2 tsp fermented black beans, rinsed and drained

½ tsp dark soy sauce

½ tsp sugar

Salt, to taste (optional)

A few slices of fresh red chilli or bell pepper for color

Place the pork in a saucepan, cover with water and bring to a boil, then simmer gently until just cooked through (probably about 20 minutes, depending on dimensions): lift it from the water with a slotted spoon and pierce with a skewer to make sure the juices run clear. Let it cool a bit, then refrigerate for several hours or overnight to cool completely.

When the meat is completely cold, slice it thinly. Each slice should have a strip of skin along the top. If your slices are very large, you may wish to cut them into a couple of pieces; each slice should make a good mouthful. Holding your knife at an angle, cut the leeks into diagonal slices.

Add the oil or lard to a seasoned wok over a high flame, add the pork slices, reduce the heat to medium and stir-fry until they have become slightly curved, some of their fat has melted out and they smell delicious. Then push the slices to the side of the wok and tip the chilli bean paste into the space you have created at the bottom. Stir-fry the paste until the oil is red and fragrant, then add the sweet fermented sauce and the black beans. Stir-fry for a few seconds more to release their aromas, then mix everything together, adding the soy sauce, the sugar and salt to taste, if you need it.

Finally, add the leeks or leaf garlic and the red pepper and continue to stir-fry until they are just cooked. Serve.

VARIATIONS

Many kinds of vegetable ingredients can be used instead of the leeks or leaf garlic. In Sichuan, the classic accompaniment to the pork is garlic leaves (

qing suan

or

suan miao

), which can occasionally be found in Chinese supermarkets in the West. You might use another Chinese variety of garlic,

jiao tou

, slicing the whole stems and bulbs on the diagonal; white onions, sliced; red or green bell peppers or a mixture of both (first stir-fry them separately to “break their rawness”); salt-preserved cabbage or mustard greens (first rinse them to get rid of excess salt); even spinach leaves.

SALT-FRIED PORK WITH GARLIC STEMS

YAN JIAN ROU

鹽煎肉

Like twice-cooked pork, this invigorating supper dish relies on chilli bean paste and fermented black beans for what they call its “homestyle flavor.” Unlike twice-cooked pork, it requires no advance preparation, so with the right ingredients on hand you can knock out a plateful in less than 30 minutes. And with its fresh, pungent greens and intensely flavored meat, it’s really all you need for a quick meal for one or two, with a good bowlful of rice, of course. Feel free to vary the vegetable ingredient as you please: red or green bell peppers, baby leeks or sliced onions would all be magnificent.