Every Grain of Rice: Simple Chinese Home Cooking (28 page)

Read Every Grain of Rice: Simple Chinese Home Cooking Online

Authors: Fuchsia Dunlop

Tags: #Cooking, #Regional & Ethnic, #Chinese

The name of this humble dish has a lovely ring to it in Chinese: it’s pronounced

pa

-

pa

-

tsai

, which literally means tender-cooked vegetables (

pa

is a Sichuanese dialect term for any food that is cooked to a point of extreme softness). Actually, it’s hardly even a dish, but a way of cooking mixed seasonal greens and vegetables that is blindingly easy and surprisingly tasty. I particularly like making

pa pa cai

after a day or two of eating rich food, when I crave something very plain, healthy and nourishing; I might serve it with some plain rice and a few cubes of fermented tofu.

Pa pa cai

is a staple of the rural Sichuanese supper table. In the old days, the vegetables were often cooked in the water beneath the

zengzi

, or rice steamer. Make it with almost any fresh greens and the vegetables you have left over in your fridge or larder: fava beans, carrots, pumpkin, eggplant, bok choy, winter melon, yard-long beans . . . The whole point of

pa pa cai

is, as they say, that it’s very

sui yi

(“as-you-please”).

According to one Sichuanese chef I know, Yan Baixian, the traditional way to prepare the chillies for the dip is to dry-roast them in a wok until crisp and bronzed then, when they’ve cooled, to rub them into flakes between the fingers.

Selection of fresh vegetablesof your choice (just for an example, try 5 oz/150g Swiss chard, 7 oz/200g new potatoes and 5 oz/150g green beans)

Salt

Ground chillies

Ground roasted Sichuan pepper

Finely sliced spring onion greens

Toasted sesame seeds (optional)

Cut your greens and vegetables evenly into bite-sized pieces. Bring enough water to cover the vegetables to a boil in a saucepan. Add the vegetables and cook until tender: it’s best to add vegetables that take longer to cook, such as potatoes, at the beginning, and vegetables that don’t take long, such as leafy greens, later on.

Give each person a dipping dish and invite them to add salt, ground chillies, Sichuan pepper, spring onion greens and sesame seeds, if using, to taste.

Serve the vegetables in the pan, or tip them into a serving bowl, with the water. Spoon a little of the cooking liquid into the dipping dishes to make a sauce. Use your chopsticks to dip the greens and vegetables into the dip before eating, then drink the liquid as a soup.

VARIATIONS

An alternative dip, if you want something richer: heat 1–2 tbsp cooking oil in a wok then, over a medium flame, stir-fry 1–2 tbsp Sichuan chilli bean paste until the oil is red and fragrant. Add a little finely-chopped ginger and garlic and/or fermented black beans too, if you like, and stir-fry until it smells rich and wonderful.

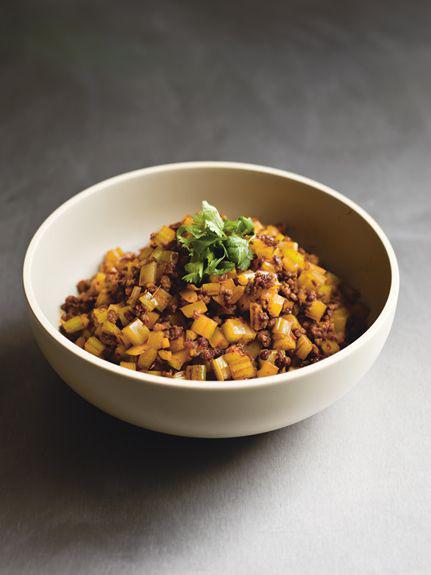

SICHUANESE “SEND-THE-RICE-DOWN” CHOPPED CELERY WITH GROUND BEEF

JIA CHANG ROU MO QIN CAI

家常肉末芹菜

Celery is considered to be a very good match for beef, because its herby flavor helps to refine the strong and muscular taste of the meat. Slender Chinese celery, which can sometimes be found in Chinese stores, is even better than the familiar Western kind, because of its superior fragrance. The following dish is typical of Sichuanese home cooking and, with its robust flavor, perfect as a relish to eat with a big bowlful of steamed rice, or for “sending the rice down” (

xia fan

), as they say in China. The celery, jazzed up by the chilli bean paste, should retain a delectable crunchiness in the final dish. You can use pork if you prefer; meat with a little fat will give a juicier result. Chef Zhang Xiaozhong taught me this recipe.

11 oz (300g) celery

3 tbsp cooking oil

4 oz (100g) ground beef

1½ tbsp Sichuan chilli bean paste

1½ tbsp finely chopped ginger

Light soy sauce, to taste (optional)

1 tsp Chinkiang vinegar

De-string the celery sticks and cut them lengthways into ⅜ in (1cm) strips. Finely chop the strips. Bring some water to a boil and blanch the celery for about 30 seconds to “break its rawness.” Drain well.

Heat the oil in a seasoned wok over a high flame. Add the ground meat and stir-fry until it is cooked and fragrant, pressing it with the back of your wok scoop or ladle to separate the strands. Then add the chilli bean paste and continue to stir until you can smell it and the oil has reddened. Add the ginger and stir-fry for a few moments more to release its fragrance, then add all the celery.

Continue to stir-fry until the celery is piping hot, seasoning with a little soy sauce, if you wish. Finally, stir in the vinegar and serve.

VARIATION

Stir-fried celery with beef

This is another supper dish that uses celery to balance the flavor of beef. Cut 4 oz (100g) lean beef steak evenly into fine slivers and marinate in a couple of good pinches of salt, ¼ tsp light soy sauce, ½ tsp Shaoxing wine, ½ tsp potato flour, and 2 tsp cold water. Trim and de-string 9 oz (250g) celery sticks and cut into fine slivers to match the beef. Cut a few slivers of red bell pepper too, if you wish, to add color. Blanch the celery and red bell pepper, if using, briefly in boiling water to “break their rawness,” then drain well. Heat 3 tbsp cooking oil in a wok over a high flame. Add the beef slivers and stir briskly to separate. Add 1½ tbsp finely chopped ginger, sizzle for a few moments until you can smell it, then add the celery and pepper, if using. Stir-fry until everything is fragrant and piping hot, seasoning with salt to taste. Stir in ¼ tsp Chinkiang vinegar and serve.

STIR-FRIED CELERY WITH LILY BULBS AND MACADAMIA NUTS

XIAN BAI HE CHAO SU

鮮百合炒素

Fresh day lily bulb is a magical, exotic Chinese ingredient, with a delightfully crisp texture. It consists of the bulbs of a plant whose dried flowers are also used in Chinese cooking. The bulbs resemble heads of garlic and can be peeled apart into petal-like flakes. It is particularly lovely in stir-fries like this, which I first tasted in the beautiful surroundings of the China Club in Beijing.

You can use cashew nuts instead of macadamias if you’d rather. Roast your own nuts for a superior crispness (tap

here

), or buy them roasted and salted. The lily bulb itself is becoming easier to find in good Chinese groceries but, if you can’t get it, the recipe will also work well with just the celery and nuts. It’s an utterly beautiful dish, whichever way you look at it.

2 celery sticks (5 oz/150g)

4 oz (100g) fresh lily bulbs

2 oz (60g) roasted macadamia nuts

⅛ tsp sugar

Salt

1½ tbsp cooking oil

4 garlic cloves, halved lengthways

De-string the celery sticks and cut each in half lengthways. Then cut each strip at an angle into diamond-shaped slices. Separate the lily bulb into petal-like sections, discarding any discolored bits; rinse and drain. If you are using roasted, salted macadamia nuts, rub them in a piece of paper towel to get rid of as much salt as possible. Combine the sugar with ¼ tsp salt and 2 tsp water in a small bowl.

Bring some water to a boil and add ½ tbsp of the oil. Add the celery and blanch for about a minute. Add the lily bulb and cook for another 20-30 seconds: both vegetables should remain crunchy. Drain well.

Heat a seasoned wok over a high flame. Add the remaining oil, then the garlic, stir once or twice to release its fragrance (but do not brown it), then add the celery and lily. Stir-fry until everything is piping hot. Pour in the sugar mixture, with a little more salt if you need it, and mix well. Finally, stir in the nuts and serve.

The pungent vegetables of the Allium family, which include garlic, onions and chives, are one of the pillars of the traditional Chinese diet. Rich in vitamin C and powerfully flavored, they complement the whole grains, legumes and Brassica greens that are the other mainstays of everyday cooking, adding a racy edge to all kinds of meals. Many different varieties and parts of these pungent plants are eaten across the country. Among the most ubiquitous are Chinese green onions, which resemble long spring onions but lack their swelling bulbs, and are an essential aromatic. They have a particular affinity with ginger and garlic. These slender onions are the original Chinese onion,

cong

, cultivated in the country since antiquity; the fat, bulbous onions favored in the West are still known in Chinese as “foreign” or “ocean” onions (

yang cong

).

Chinese chives, also known in English as garlic chives, are radiantly delicious and one of the most important ingredients in simple supper stir-fries and dumpling stuffings. More substantial than the familiar herb chives used in Western cooking, they grow in clumps of long, flat, spear-like leaves and have a deep green color and an assertive garlicky flavor. They rarely play the leading role in a dish, but are used to flatter and enhance ingredients such as firm or smoked tofu, pork, bacon, chicken, beef, lamb, venison, or beaten eggs (apart from eggs, these ingredients will normally be cut into fine slivers to complement the narrow chives). One simple stir-fry of this sort takes a few minutes to make and can serve as lunch for one or two people. Asian-grown Chinese chives are easy to find in Chinese groceries, but I hope before too long that this adaptable vegetable will be cultivated locally and available in mainstream supermarkets.

Aside from the most common garlic chives, the Chinese eat flowering chives—which are sold in bunches of thin stems topped with tiny flower bulbs—and yellow hothouse chives, which are forced to grow in darkness like rhubarb and chicory. Wild garlic (otherwise known as ramsons, or ramps in America) can be a good substitute for Chinese chives in dumpling stuffings and some other recipes, although its fragile leaves wilt more quickly in the heat of the wok, so it’s less suitable for stir-frying.

When it comes to garlic, cloves are used whole, sliced, finely chopped or mashed to a paste. They may also be pickled or, in some regions, eaten raw with a lunch of steamed buns or noodles. Another variety of garlic, known in different regions as “garlic sprouts” (

suan miao

), “green garlic” (

qing suan

) and “big garlic” (

da suan

), adds a bright, refreshing pungency to rich dishes such as Twice-cooked Pork and Pock-marked Old Woman’s Tofu. With long green leaves and white stems, it resembles Chinese green onions, except its leaves are flat like those of leeks, rather than tubular. It can be hard to find outside China: if you come across it, snap it up.