Everything Beautiful Began After (11 page)

Read Everything Beautiful Began After Online

Authors: Simon Van Booy

Henry was a child archaeologist.

At nine years old he dug up a piece of flint that resembled an axe head. His father took him to the University of Swansea. They asked for the archaeology department and were directed to a tall concrete block with untidy rows of bicycles outside.

A long-haired student asked if they were lost. Henry produced his flint, as though it were proof of something. The student stared at it.

“Do you have an appointment?” he said.

“No,” said Henry’s father. “We thought we’d just pop in.”

“Well, I suggest you look for Dr. Peterson’s office,” the student said, tossing his mane. “He’s good with this sort of thing.”

Professor Peterson was much younger then, but to nine-year-old Henry he seemed a very old man. He scrutinized the artifact with a magnifying glass. Then he looked at Henry with his magnified eye.

“I can deduce that it’s extremely old,” he said. “May I ask how old you are, young man?”

“Nine,” Henry said. “Actually, nine and a half.”

Professor Peterson set the magnifying glass down on a piece of felt and looked at the artifact again. “I’m afraid it’s a great deal older than you.”

“I knew that,” Henry said excitedly. “Is it as old as dinosaurs?”

“Older,” Professor Peterson stated without flinching. “Your artifact would have been used to hunt them.”

“To hunt them?”

“Oh yes,” said Professor Peterson. “Not only for food, but for their pelts.”

“Their pelts?”

“The ancients wasted nothing.”

“What should I do with it?”

“There’s really only one place for it.”

“Where, Professor?”

“In your bedroom under a glass bowl for protection.”

Professor Peterson handed the flint back to Henry.

His father stood up to leave.

“Actually,” said Henry, “I want you to have it.” He held out his rock to the professor with two small hands.

Professor Peterson blushed.

“You should keep it, Henry.”

“But don’t you need it for research?”

“But, Henry—you found it—it belongs to you.”

“But if it’s so precious, doesn’t it belong to everyone?”

Professor Peterson took the flint and set it on his desk.

“Please sit down,” he said to Henry’s father.

“Years from now, I want you to look me up, and when this young man is older, I’d like to help with his education—if he’s still interested in all this.”

“I definitely will be,” Henry interrupted.

“That’s nice of you, Professor,” said Henry’s father.

“Nice has nothing to do with it,” Professor Peterson snapped. “I need men like your Henry. People with faith.”

Henry’s father looked away. His wife would be at home in the bedroom they use for storage, sitting on the carpet. She would be out when they got back—walking in the fields beyond the house.

He would fry eggs and make toast. Henry would watch. They would eat together in front of the television, watching

Blue Peter

.

Professor Peterson took the flint and set it next to an ashtray of old stamps. Then he took a key from his waistcoat pocket and opened a glass cabinet behind his desk. It was full of strangely shaped things. He carefully removed a fossilized dinosaur egg and turned around.

“Here,” he said, handing it to Henry. “I was given this when I was your age by my father. It belongs to you now.”

For the next twelve Christmases, a box of the year’s archaeological books and journals would arrive by post to the small semidetached house in Wales where Henry spent his childhood.

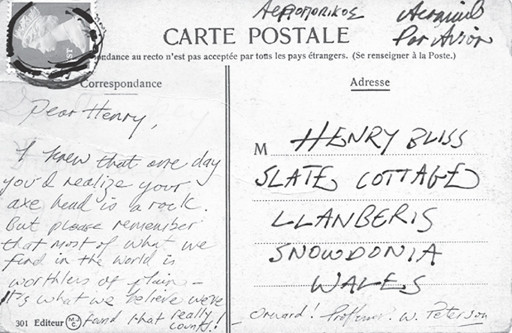

After about three years, however—Henry realized that all he’d found in the garden that afternoon was a flint in the shape of an axe head.

He wrote this in a letter to Professor Peterson, who was in the Middle East at the time. A month later, Henry received a postcard from somewhere very far away with writing he didn’t recognize.

On a mountain high above Athens, two figures leaned over a kitchen table in the blazing sun.

“This is peculiar,” Professor Peterson said, handing a magnifying glass to Henry. “I have a funny feeling it might be Lydian.”

“That doesn’t seem likely.”

The professor was referring to a discus the size of a dinner plate.

Henry spent the afternoon not thinking about his work. His old British dental tools scratched the ground but revealed only more questions about Rebecca. About eleven o’clock, Henry washed his hands over the sink, pumping the foot pedal to draw water. The professor appeared from the tent.

“Let’s take that discus down to the college now,” he said. “With Giuseppe away, it’s our only chance.”

“I was going to have lunch,” Henry said.

“Good, good, we’ll eat together at Zygos’s Taverna.”

Professor Peterson’s car occupied the extremely rare privilege of being the most battered automobile that had ever clunked and overheated its way along the Athenian roadways.

It was a dirt-brown Renault 16 the professor said he had bought when he still had hair. He had driven it over 1.3 million miles, most of which were accrued on long desert roads in the Middle East. According to the professor, the mileage clock had broken in 1983 and then started going backward in 1989. The professor said that when it got to zero, he would give it back to Renault with a ribbon tied around the bumper.

The dashboard was a mass of twisted wires (one of which was live) and the instruments were too dusty to read. Pinned to the sagging upholstery roof were photographs of the car at famous digs in Europe and the Middle East. According to the professor, the car had led a far more interesting life than any one person he had ever met. It was once stuck in the sand in Egypt and had to be pulled out by camels. It took two bullets running the Iraqi border into eastern Turkey with a half-ton statue strapped to the roof that Professor Peterson had stolen from thieves who had stolen it from pirates who had stolen it from an international arms dealer. In the end it turned out to be a fake.

In snowy Poland at Biskupin, the old Renault had rolled down a small embankment, almost crushing a Polish archaeologist, who was saved only by her enthusiasm for archaeology—the depth of her excavation pit. It was stolen in Nigeria, only to be abandoned that afternoon when the thieves realized the entire backseat had been taken over by a fourteen-inch Hercules Baboon spider.

The professor sat in the car with his foot on the brake pedal while Henry removed the bricks from under the wheels that prevented it from rolling off the cliff.

The car was missing several windows and the sunroof had rusted open in 1986 during an African rainy season.

The professor had converted the trunk of the car into a soft nest of blankets and hammocks—not as a place to sleep, but as a safe haven for whichever artifact he was transporting at the time. The professor boasted of the various artifacts he’d had in the backseat the way a teenager brags about sexual conquests.

They careened down the side of the mountain without talking. Then they trundled through the iron bridge, at which point the professor began to talk and talk. Henry could hear nothing except the engine, and a strange banging that came from underneath whenever Professor Peterson tapped the brake pedal.

At the first traffic light on the edge of the city, Henry was finally able to hear what the professor was saying.

“And did you know I once had an infestation of killer bees in this car?”

Henry replied that he did not know, but suspected a joke. The light turned green.

At the next red light, the professor was suddenly audible again.

“ . . . with several newborns. Newborns!”

When the light changed, the professor pulled across six lanes of traffic to the fury of other drivers, and then turned abruptly down a side street. He was a dangerous driver—which in Athens meant he was safe. Despite being almost eighty years old, he had adopted the Greek custom of ignoring every important red light and only pulling out to overtake a slower car when he spotted a vehicle racing toward them in the opposite direction.

As the professor swung the Renault down an even narrower side street, a figure stepped into the road from behind a parked car. The Renault’s fender clipped him hard and from the corner of his eye Henry saw a body sprawl onto the sidewalk.

The professor skidded to a stop. Henry threw open his door and sprinted back to the motionless body of the man on the ground. He was wearing a crumpled tan suit that was torn under one arm. Henry knelt down and began a routine he’d practiced in his first-aid classes. The man was alive and breathing—but seemed barely conscious. He also appeared to have a black eye and stitches in his face.

“My god, look at him,” the professor said. “What have I done? My god, my god.”

“I won’t know how badly he’s hurt until he comes around and I can talk to him—or we take him to hospital ourselves.”

“My god,” the professor said. “This is unbelievable.”

“I know—his face has taken a bit of a knock.”

But then the man on the ground opened his eyes. He took a long breath and let his gaze fall sullenly upon the two men standing above him.

“Something’s happened to me, hasn’t it?” he said.

Professor Peterson and Henry recoiled at the stench of anise, fennel, and raisins—the ingredients of ouzo.

The professor nudged Henry and mouthed the words, “He’s blind drunk.”

“Yes,” the professor said. “Something has happened to you.”

“You speak English?” Henry said to the man.

“I clipped you with the car,” the professor interrupted. “You stepped out into the road, you understand,” the professor leaned down. “I’m very, very sorry, old chap.”

The man tried to sit up.

“No, no, it’s all my fault,” the man admitted. “Wine.”

“You’re drunk?” Henry said.

The man seemed not to hear.

“Are you in pain?” Henry asked.

“Not any more than usual, I suppose,” the man admitted with a strange smile.

Henry and Professor Peterson helped him to his feet. He introduced himself as George. His pants were also ripped and there were bloodstains around the tear.

“Sorry we almost killed you, George, but tell me,” Henry said, “what are all those bruises on your face and the stitches?”

“Oh, these darlings?” George said casually. “A common misunderstanding.”

“Have you been to hospital?” the professor asked.

George shook his head. “There’s little point—the human body is capable of sustaining much worse.”

“Well, George—I’m Professor Peterson, an archaeologist digging here in Athens, and I have rooms at the university, you understand. Let’s go there now. Henry here—who has a certificate in first aid—can patch you up properly and make sure you don’t need any X-rays.”

“If you really think I need looking after,” George said. “I’ll go with you.”

Henry helped George climb into the long backseat of the Renault.

“It’s filthy back here,” George muttered.

“Would you mind driving, Henry?” the professor said.

“Why is it so dirty back here?” George said again.

“Ever hear of a Nigerian Hercules Baboon spider?” the professor exclaimed.

“Definitely not,” George said.

Henry watched him in the mirror—not with coolness or relief, but with a compassion that extended beyond the moment, as though behind the bruised eyes and the quivering mouth he could sense the presence of a small boy the world had forgotten about.

Professor Peterson’s office was the most dangerous place on campus. Books piled ten feet high leaned dangerously in various directions. On the tallest tower of books, a note had been hung halfway up:

Please walk VERY slowly or I may fall on you without any warning, whatsoever.

There were three oak desks with long banker’s lamps that the professor liked to keep lit, even in his absence. On his main desk were hundreds of Post-it notes, each scribbled with some important detail or addendum to his thoughts. There were also hundreds of pins stuck in a giant map that had been written on with a fountain pen. The ashtrays were full of pipe ash and the room had that deep aroma of knowledge: old paper, dust, coffee, and tobacco.