Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard (100 page)

Read Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard Online

Authors: Richard Brody

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Performing Arts, #Individual Director

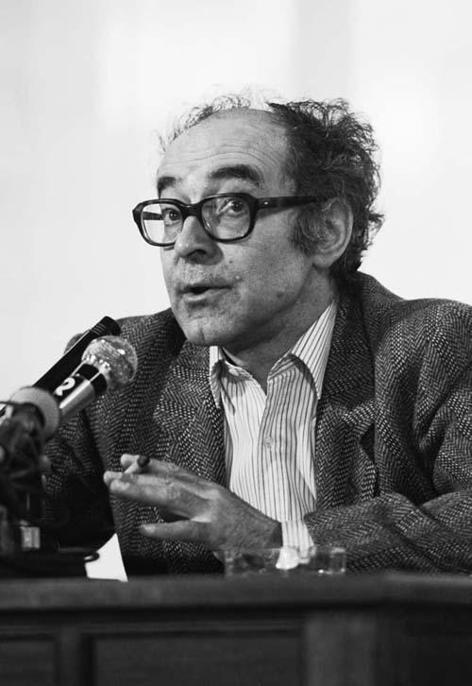

Godard presents the first draft of

Histoire(s) du cinema

at the Cannes festival, May 21,1988.

(AP Images)

twenty-four.

HISTOIRE(S) DU CINÉMA

, PART 1

“I’d like to make a film on the concentration camps”

T

HOUGH

G

ODARD HAD BEEN TALKING ABOUT MAKING HIS

personal history of cinema since the mid-1970s and had announced plans for it in 1983, he did not start work on it until signing a contract with Gaumont in 1985. At that time, after hiring a full-time cameraperson, Caroline Champetier, and an assistant, Hervé Duhamel, he asked Champetier to buy the entire series of videocassettes of classic films,

Les Films de ma vie

(The Films of My Life). According to Champetier, when the tapes arrived, “he spent lots of time organizing them, and he wouldn’t let anybody else touch them. Then he watched them—and he thought that he had to watch the entire film to find one shot.” As he explained to her, “Nobody takes into account the screening time”;

1

he knew that the project would take a long time to complete.

The original impetus for the series had been his and Gorin’s meditations on the political implications of cinematic form. In the 1970s, as Godard set out on his slow return to the cinema, he thought he could make money with his knowledge of film history, but then the project turned into an autobiographical tour through his own experience of that history. But in 1985, Godard landed on a third principle to orient the entire project, the passage from the history of cinema to history as such. Godard’s view of political history rapidly came to dominate the series—which, as it turned out, took him more than a decade to complete—and all of his subsequent work.

O

N

A

PRIL

24, 1985, Claude Lanzmann’s epochal film

Shoah

opened in Paris. The film—the Hebrew title means “catastrophic upheaval”—provided

the French with a new word to designate the Holocaust.

2

It also provided the French with a new frame of reference for the devastation wrought upon the Jews of Europe, a view derived from Lanzmann’s method for studying it.

Shoah

features no archival footage; it is made entirely of images filmed by Lanzmann in the 1970s and 1980s, mainly featuring the people he interviewed: Jews who survived the concentration camps, Germans who participated in the camps’ functioning, and Poles who lived near the camps. Starting from the principle of the moral primacy of testimony, Lanzmann recovered the events of history from their enduring (if subordinated) presence in the current world.

Shoah

is a film of history that takes place entirely in the present tense.

Years before Lanzmann’s film was released, the Holocaust was already on Godard’s mind as a potential subject. As early as 1963, he had imagined what he called “the only true film about the concentration camps,” which he thought could never be made because “it would be intolerable.” Such a film would concentrate on the practical problems that the “torturers” faced:

How to get a two-meter body into a fifty-centimeter coffin? How to dispose of ten tons of arms and legs in a three-ton truck? How to burn a hundred women with only gasoline enough for ten? One would also have to show the typists typing out lists of everything. What would be unbearable would not be the horror aroused by such scenes, but, on the contrary, their perfectly normal and human aspect.

3

During the 1980 Cannes festival, where he was presenting

Sauve qui peut

, Godard offered a different view of the subject: “I’d like to make a film on the concentration camps. But one must have the means. How to find twenty thousand extras who weigh thirty kilos? What’s more, one would have to really beat them. But what assistant would be willing to beat up a skeletal extra?”

4

Behind the flip remark, Godard implied the serious notion that no fiction film about the concentration camps could adequately convey their horror. But he added, cryptically, “The camps—nobody has ever shown them.”

5

In the years that followed, Godard repeated this remark and unpacked its meaning: he made many references to his certainty that the Germans had produced images of the concentration camps and that these images had not been seen for the simple reason that nobody had done the archival research to find them. For instance, in 1985, he asserted:

The camps were surely filmed in every which way by the Germans, so the archives must exist somewhere. They were filmed by the Americans, by the French, but it wasn’t shown because if it had been shown, it would change something. And things mustn’t change. People prefer to say: never again.

6

Godard was, at the time, unimpressed by

Shoah

. In a televised discussion with Marguerite Duras in December 1987 (one of the many broadcasts that served as advance publicity for the release of

Soigne ta droite

), Godard deprecated Lanzmann’s film, complaining that it did not show what had happened: “But it suffices to show; there still exists such a thing as vision.” Duras defended

Shoah

, claiming that “it showed the roads, the deep pits, the survivors.”

G

ODARD

: Lanzmann didn’t show anything—he showed the Germans.

D

URAS

: One is invaded by the images.

G

ODARD

: It isn’t broadcast every Monday.

D

URAS

: But that’s something else.

G

ODARD

: But that’s the thing I’m talking about. If it had been seen, people wouldn’t judge [Klaus] Barbie as he’s been judged.

Godard seemed to suggest that the widespread responsibility for the camps adduced in

Shoah

would have prevented the quasi-expiatory demonization of Klaus Barbie, the head of the Gestapo in Lyon as of May 1942, who was arrested in Bolivia in 1983, tried in France in 1987, and convicted of crimes against humanity.

7

Then, regarding

Shoah

, Godard added, “The film wasn’t shown in’ 45.” In response to his critiques, Duras gets visibly and audibly angry; her tone rises as she declares, “It’s an absolute reference. Let’s not talk about it, we won’t talk about all this, it’s a horror.” While she scolds Godard for his critical detachment from Lanzmann’s film, he looks chastened and lowers his eyes.

For Godard, the crucial aspect of a cinematic approach to the Holocaust was the presence or absence of footage of the camps themselves, of the actual killing of inmates. This idea determined his response to

Shoah

—and ultimately his creation of

Histoire(s) du cinéma

. Indeed, that series of videos, on which Godard began work in 1985, is most clearly understood as Godard’s response to

Shoah

, his counter-

Shoah

.

During an interview from 1989, as he was completing the first two of the eight episodes of

Histoire(s)

, Godard emphasized the centrality of World War II to his series, “because that’s where everything”—the cinema—“came to a halt.” This historic break in the history of cinema occurred, in his view, because “nobody filmed the concentration camps, no one wanted to show them or to see them.”

8

The world’s (though primarily Europe’s and America’s) film industries were responsible for two crucial

failures—to make fictional films about the camps at the time that they existed, and to find the German footage Godard believed existed. He argued that the result of this failure was “the death of the European cinema and the triumph of the American cinema.”

9

Godard’s thesis reflected his view of the power of the cinema and his assumption that the medium’s overwhelming popularity would have compelled a worldwide public outcry against the Holocaust, had it only been shown in movies. He took for granted the power of images—whether authentic documentary ones or fictional ones that offered irresistible, psychologically rich and subtle simulacra of reality—to inspire viewers’ confidence, compel their belief, and arouse their outrage.

This failure, according to Godard, signified the abandonment of cinema’s documentary essence in favor of its spectacular side, which he took to be Hollywood’s specialty. And the postwar success of the American cinema (which in fact captured a large share of the European market) meant, to him, that the intrinsically historiographic aspect of the cinema was also destroyed—because, in his view, the essence of America was its lack of history (an assertion that he would elaborate in interviews and films). He considered the renunciation of documentary and history to represent nothing less than the end of the cinema.

The end of the cinema, as Godard understands it, is the thesis he expresses in the opening episodes of

Histoire(s) du cinéma

. The series is the embodiment of a single, dominant, coherent argument, which Godard himself voices with the clarion directness of a lecturer—often on-screen. Completed in 1998, the series is not widely recognized as the clear statement that it is because the form in which Godard couches his argument is the most complex that he had realized to date. The video series is also demanding in its length, which is just over six hours.

In

Histoire(s) du cinéma

, Godard assembled a vast number of film clips, still photographs, on-screen texts, and images of himself and other performers in recitation and discussion, as well as music, film sound tracks, and voices, including his own. He joined these disparate elements in an allusive collage featuring a wide array of editing devices and optical effects, such as superimpositions, flashing alternations, and slow dissolves, and the sudden clash of contrasting elements, whether color and black-and-white, light and dark, or quiet and loud. Godard drew the strands of thought related to his thesis into an amazingly intricate web of guided visual and audio associations. But ultimately, the most remarkable aspect of

Histoire(s) du cinéma

is not its complexity but its simplicity. The text of Godard’s own remarks, mainly in voice-over, would—if transcribed—comprise a concise exposition of a powerful set of arguments.

10

The first section, 1A,

Toutes les histoires

(

All the Stories

), asserts, in Godard’s voice, that the fall of the cinema came about not through the transition from silent to sound films but as a result of the absence of images made during World War II, in fictional films—especially from Hollywood—of the concentration camps. The second part of the thesis, expounded in section 1B,

Une histoire seule

(

One Story Alone

), is personal, an attempt to trace the effect on Godard himself of his lifelong devotion to that decadent cinema—a devotion that began in the early postwar years.

The

Histoire(s)

, with their rapid superimpositions and blinking alternations of images, convey an associative intensity of experience that defies description or explication from a single regular-speed viewing. Godard uses video analytically, in a particular sense of the word: the freedom of association of images and sounds is reminiscent of the work to which an analysand is subjected by a psychoanalyst. In fact, Freud is a major reference in the series, and its central consciousness, its thinking subject, is Godard’s own cinematic self.

The result is a sort of cinematic confessional, as Godard defines his own work and life in the cinema in terms of his faith in this fallen art form—and ultimately, its personal and moral price.

Histoire(s) du cinéma

can be understood as an intellectual autobiography, in which the subject (Godard’s own story) and the object (the history of cinema) converge in a single circuit of thought. This subjective element of the series, a kind of working-through on screen of the network of associations that formed in Godard’s movie-colonized unconscious—the logical extension of his notion that “at the cinema, we do not think, we are thought”—becomes a kind of cinematic self-psychoanalysis, in which the profusion of night thoughts and daydreams is oddly, decisively dominated by a single idée fixe: the cinematic nonrepresentation of the Holocaust.

G

ODARD’S

H

ISTOIRE(S)

ARE

stories in yet another sense: his notion of history is comprised of stories, anecdotal history, and the opening episodes consist of clusters of good yarns that relate to his central themes. In section 1A,

All the Stories

(dedicated to Mary Meerson, Henri Langlois’s longtime companion), he recounts “the story of the last tycoon, Irving Thalberg,” who imagined “fifty-two films a day,” and of whom Godard said, “it”—this fertile imagination—“had to pass through a beautiful and fragile body” (the handsome Thalberg died of pneumonia at age thirty-seven, in 1936) “so that, as Fitzgerald put it, ‘this’ could come to pass—this, the power of Hollywood.” He tells of Max Ophüls’s failed attempt to film Molière’s

School for Wives

in Geneva in 1940, with the actress Madeleine Ozeray, and crudely correlated the German director’s affair with the French actress with the invasion of France by Germany: “He falls on Madeleine Ozeray’s ass just as the German

army was taking France from behind.” Godard tells the story with which he had harangued the cameraman Bruno Nuytten on the set of

Detective

, concerning the camera manufacturer Arriflex, “which Arnold and Richter invented to keep up with the German army.” He suggests, hauntingly, that the cinema foretold the coming of war and the concentration camps, in such scenes as the death of Boieldieu in Renoir’s

The Grand Illusion

, the shooting of rabbits in the same director’s

The Rules of the Game

, the skeleton dance in the same film, or the death of the hero in Fritz Lang’s

Siegfried

. And Godard summarizes the cinematic tragedy in wartime: that before the war, spectators in movie theaters “burned the imaginary to warm the real,” and that afterward, “reality takes its revenge and demands real tears and real blood.”