Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard (2 page)

Read Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard Online

Authors: Richard Brody

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Performing Arts, #Individual Director

Godard is undoubtedly best known for his first feature film,

Breathless

, which he made in 1959. A highly personal yet exuberant refraction of the American film noir,

Breathless

was gaudily emblazoned with its technical audacity as well as with Godard’s own artistic, literary, and cinematic enthusiasms. Even now,

Breathless

feels like a high-energy fusion of jazz and philosophy. After

Breathless

, most other new films seemed instantly old-fashioned. The triumph of Godard’s longtime friend François Truffaut at the 1959 Cannes festival with

The 400 Blows

, had announced to the world the cinematic sea change effected by a group of critics-turned-filmmakers already known in France by the journalistic label of

la nouvelle vague

, the New Wave. But

The 400 Blows

was only the setup.

Breathless

was the knockout blow. If

The 400 Blows

was the February revolution,

Breathless

was October.

After

Breathless

, anything artistic appeared possible in the cinema. The film moved at the speed of the mind and seemed, unlike anything that preceded it, a live recording of one person thinking in real time. It was also a great success, a watershed phenomenon. More than any other event of its time,

Breathless

inspired other directors to make films in a new way and sparked young people’s desire to make films. It instantly launched cinema as the primary art form of a new generation.

In the 1960s, Godard’s films were eagerly anticipated events—in France, in the United States, and around the world—and each new release seemed to leave the last far behind. Writing in February 1968, Susan Sontag called Godard “one of the great culture heroes of our time”

1

and compared the aesthetic impact of his work to that of Picasso and Schoenberg. Mercurial, puckish, combative, and increasingly politicized, Godard was hailed during his 1968 speaking tour of American universities as being “as irreplaceable for us as Bob Dylan.”

2

Yet when Godard came to the United States that year for a celebrity tour of American universities, he was actually in a state of crisis and doubt. Even as his fame and his inventiveness increased through the 1960s, he became confused and uncertain in his work, which was being pulled in opposite directions by its

fictional and nonfictional elements, by its personal and political implications. As the pace of social change outstripped his ability to invent new forms to engage it, Godard became increasingly strident in his response to the world around him. In his frustration, he also became increasingly hard on himself. Indeed, his films became public confessions and self-flagellations, but they were executed so effervescently, so inventively, so cleverly—with such a flamboyant and youthful sense of freedom—that they were most often received by critics and viewers as virtuosic displays of experimental gamesmanship.

The last of this torrent of films,

Weekend

, concludes with two title cards: the first reads “End of Film” the second, “End of Cinema.” When Godard finished filming

Weekend

, his fifteenth feature film in eight years, he advised the regular members of his crew that they should look for work elsewhere. He spent the next few years seemingly underground, working in a frenzied yet sterile engagement with one of the doctrines of May 1968, a nominal Maoism. After years of intellectual woodshedding and a period of artistic and physical convalescence (following a serious motorcycle accident), he returned to the French film industry in 1979. The films and videos he has made since that return are works of an even greater originality and a more reflective artistry than those of the 1960s, but Godard has never recovered his place at the center of his times.

I

N A CERTAIN SENSE

, Godard has been a victim of his own artistic success. Ashe fulfilled, after long delay, the underlying promise of the French New Wave—to turn movies into an art form as sophisticated and as intellectually powerful as literature or painting—his work became far too allusive and intricate for the wide range of moviegoers. In the earlier films, splashy borrowings from American movies and the presence of pop culture icons and iconography of the day went a long way to keep Godard in fashion even when his approach to them reflected the challenging philosophy of Jean-Paul Sartre or Claude Lévi-Strauss. Yet in his later work, Godard became even more intensely serious and demanding. His previous films represented a dismantling of movie conventions and forms; in his subsequent work he took on the colossal task of an aesthetic reconstruction of the cinema based on its excavated historical elements. Holding the present day up to comparison with the high points of cultural history, Godard found it wanting; his critique—indeed, utter rejection—of the contemporary culture of mass media made many people, especially the younger generations raised on that culture, simply wish that he would lighten up.

Lightening up is a notion profoundly at odds for a filmmaker who has made the greatest possible claims on behalf of the cinema’s unique relation to reality and to history, of its power to transform whatever comes within its purview. As Godard told me, “Everything is cinema.” Indeed, for Godard,

the cinema is the art of arts, encompassing and channeling the full spectrum of what is human, from the broadest political currents and the other art forms to the most intimate reaches of his own life. For Godard, the cinema has always been inseparable from his personal experience—and his own identity has been inseparable from the cinema. His initial enthusiasm for movies had the force of a religious conversion, and his critical account of the medium’s unique psychological power derived from his own overwhelming encounter with it. As a filmmaker, he invented ingenious and ever-more-elaborate means by which to relate both the substance and the form of his work to his own inner and outer life, whether through his relationships with his performers (including his two wives, Anna Karina and Anne Wiazemsky) or with his collaborators (including his longtime companion, Anne-Marie Miéville), or through his own forthright yet shifting presence in the films.

Moreover, no other director has striven so relentlessly to reflect in his work the great philosophical and political debates of the era: World War II and its political aftermath in France; the uses and abuses of existentialism in the postwar years; the structura list revolution; the demise of Stalinism and the rise of the New Left; the growth of modern consumer society and its political fallout in May 1968; the vast sea change and social heritage of the late 1960s; the hopes and disappointments of the Mitterrand era; Holocaust consciousness and the recuperation of historical memory; new fronts of battle after the end of the Cold War; and the current era of big media and what might be called the American cultural occupation of Europe. But despite Godard’s ongoing attention to the crucial questions of the day, his approach to them has in recent years become so intricately interwoven with his advanced aesthetic methods, so rarefied, Olympian, and oblique, that many critics and viewers have instead rejected these later efforts outright, asserting that he has somehow grown detached from political reality.

In fact, Godard’s later work is marked by his obsession with living history. But this obsession has brought with it a troubling set of idées fixes, notably regarding Jews and the United States. In recent years Godard’s vast aesthetic embrace of the entire Western canon, from Greek mythology and New Testament prophecies to twentieth-century modernism, has gone hand-in-hand with his borrowing of some of the prejudicial assumptions of that cultural aristocracy. Contemplating the contemporary world in the light of lost traditions, Godard has adopted traditional attitudes as well, including several shared by some of the most discredited and dangerous ideologies of his times. Yet these invidious views have eluded widespread discussion, largely due to the abstracted forms in which his films embody them, their quiet place beside his more brazen media provocations—and, perhaps,

to the ready audience that the films still find among the cultural avant-garde. Godard’s edgy relations with the media may have rendered his deepening isolation inevitable. From the start of his career, Godard made use of the press to help effect the personalization of his work. He turned the elements of his celebrity—in particular, the interview—into a parallel art form that illuminates and informs his films. He continues to fascinate the French press and remains an object of its attention; and he retains his fascination precisely by remaining himself, by not tailoring his public statements and behavior to the deferential or cautious norms of the media. Indeed, the more stringently he criticizes the fashions and conventions of public discourse, the more interesting he becomes to the objects of his opprobrium.

With his critique of the media, however, goes a deep understanding of the mechanism of celebrity and its crucial significance, especially now, in the creation and decadence of art. Godard’s analysis of the media, which is an integral part of his work, is centered on what he considers their noxious effect on culture, on human relations, and particularly on the cinema. And because his faith in the cinema has been so great, and because he conceives his own identity in relation to it, Godard has taken on great personal, political and historical burdens in the name of the entire cinema. Thus, his later works and his public image have been marked by a sort of self-deprecating humility, even penitence. His blend of fierce prophecy and long-suffering sainthood have given his fame an odd twist. Though Godard remains a celebrity of sorts, especially in France, he has an air of taboo about him, like a great Dostoyevskian sinner who has come through his ordeals sanctified.

I

F EVERYTHING IS CINEMA

, then approaching Godard’s vast work in any meaningful way necessarily means being prepared to deal with everything: politics, art, philosophy, history, nature, beauty, lust, torment, money, love, and the random element. True to the films,

Everything Is Cinema

is a book of correspondences, an attempt to discover and to observe the associations of the crucial elements in Godard’s life, work, and times. It is a book that moves from his very first critical articles through all of his major films, all the while showing how his art is intertwined with his personal and intellectual experience and is inseparable from the social, aesthetic, and philosophical currents of the era.

Jean-Luc Godard is an artist as dominant, as crucial, as protean, and as influential as Picasso, but he is a Picasso who vanished from public consciousness and from the encyclopedias after the first heady flourish of Cubism. My hope is to provide guideposts that will help readers and movie watchers accompany Godard from his time of promise through the early years of flamboyant innovation, but also far beyond—on the long, lonely, yet exhilarating and indeed epochal journey of his artistic life.

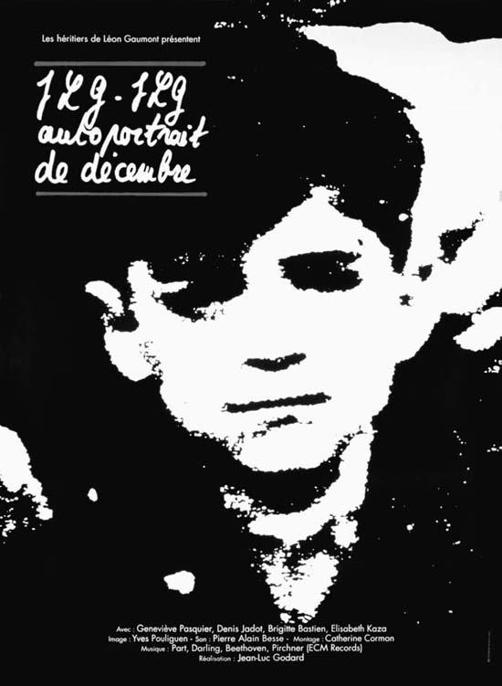

EVERYTHING

IS CINEMA

A photograph of Jean-Luc Godard at age ten, as it appears in his film

JLG/JLG

(1994) (

TCD-Prod DB © Gaumont/DR

)

one.

“WE DO NOT THINK,

WE ARE THOUGHT”

I

N THE SECOND EDITION, DATED

J

UNE 1950, OF A THIN

newspaper-like magazine published in Paris,

La Gazette du cinéma

, a nineteen-year-old writer made a modest debut. Jean-Luc Godard’s article, simply titled “Joseph Mankiewicz,” was a short and breezy overview of that director’s career, though, as in the following reference to the director’s recent film,

A Letter to Three Wives

, it was devoted less to his films than to Mankiewicz himself: “‘One can judge a woman’s past by her present,’ Mankiewicz says somewhere: this letter to three married women is also three letters to the same woman, one whom the director probably loved.”

In an eight-paragraph jaunt, the young writer lightly sketched a conception of the cinema that was as intensely personal as it was revolutionary: he suggested that films are one with the world offscreen. Casually, and without any theoretical fuss, he treated films as something more than creations that bore the mark of their makers; he considered them inseparable from the lives of their creators.

Godard’s piece on the front page of the next issue of

La Gazette

, “For a Political Cinema,” is as provocative now as it seemed at the time. In it, he put forth an aesthetic framework that daringly overrode basic ideological distinctions in the name of specifically cinematic values.

One afternoon, at the end of the Gaumont newsreel, we opened our eyes wide with pleasure: young German Communists were marching in a May Day celebration. Suddenly, space was only the lines of lips and bodies, time only the raising of fists in the air… By the sole force of propaganda that was animating them, these young people were beautiful.

1