Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard (58 page)

Read Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard Online

Authors: Richard Brody

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Performing Arts, #Individual Director

F

ROM THE OUTSET

of

Two or Three Things

, Godard once again blamed the moral corruption of a woman he loved on industrial modernism. To accompany the images of large-scale urban construction that begin the film, Godard whispers on the sound track a diatribe against the government’s construction of housing projects, capping his charges with the claim that this policy “accentuates the distortions of the national economy, and even more, the distortions of the ordinary morality on which the economy is based.”

The connection between

Two or Three Things

and Godard’s earlier analytical antimodernist films,

Le Nouveau Monde

and

A Married Woman

, is emphasized by another of Godard’s editing-room decisions, the use once again of Beethoven’s string quartets on the sound track. But the new film added a novel element to the critique: the American cinema, which was now considered to be a part of the consumerist landscape. The film ends with the shot of a pack of Hollywood brand chewing gum and an array of packaged goods:

I listen to the advertising on my transistor radio. Thanks to Esso [spelled out “E-SS-O”] I drive at ease down the street of dreams and I forget the rest. I forget Hiroshima; I forget Auschwitz; I forget Budapest; I forget Vietnam; I forget the minimum wage; I forget the housing crisis; I forget the famine in India. I have forgotten everything, except that, since I’m being brought back to zero, it is from there that I will have to start again.

The zero to which Godard had been brought was both romantic (the loss of the glossy ideal of true love) and cinematic (the loss of Hollywood as an example to follow). In an interview, he declared the need “to flee the American cinema,”

56

but he had nothing to offer in its place. The film’s principle of construction was itself a virtual cinematic zero, a simple alternation of city and object footage with narrative or anecdotal sequences. With

Two or Three Things

, Godard reached the culmination of a process of decomposition and fragmentation that had begun with

Le Nouveau Monde

. Romantic despair had corroded his attitude toward both modernity and cinema. One more short film would provide a poignant, self-lacerating coda to the series.

SUZANNE SCHIFFMAN’S PRODUCTION

notes for

Made in USA

show that Godard, despite his doubts, intended to pick up the pace of production. He planned to direct a short film from September 15 or 20 to October 10; to make

La Bande à Bonnot

in December and January 1967; and in between, he would finally do

Pour Lucrèce

. The short film—like

Le Nouveau Monde

, a work of science fiction—was the only one of these projects to be realized.

Producer Joseph Bercholz

57

commissioned the film as part of a compilation,

The World’s Oldest Profession

, that was to include six directors’ sketches on prostitution through the ages: the prehistoric, the Roman era, the French Revolution, “la belle époque” (the 1890s), the present day, and the future. Godard’s theme was announced in the film’s title,

Anticipation, or the Year 2000

, and was explained in the credits as a view of prostitution in “the intergalactic era.”

58

The lead role—of a prostitute—would be played by Anna Karina.

After

Vivre sa vie, Alphaville

, and

Two or Three Things

, Godard seemed to have become something of a cinematic specialist in the field of prostitution. He explained, after completing

Two or Three Things

, that the theme inspired him because it exemplified one of his “most deeply rooted ideas,” that “to live in Parisian society today, one is forced, at whatever level, whatever stratum, to prostitute oneself in one way or another, or what’s more, to live according to laws which resemble those of prostitution.”

59

The antithesis of prostitution was, in Godard’s view, love. In

Vivre sa vie

and

Alphaville

, women were prostitutes when they did not love, and were

redeemed from the bondage of prostitution by the awakening of love. In

Two or Three Things

, Juliette, who experienced no romantic revelation, ended the film as she started it, as a prostitute.

Anticipation

, which Godard filmed in November 1966, took up the same theme but resolved it differently. In effect, the film dramatizes another man’s happiness with Karina, and as such, it is a film of keen personal agony, mitigated only by the fact that Godard himself was already onto a new life and was closing the book on the old one with a harsh judgment of the final state of things.

Anticipation

was the last film that Godard and Karina made together, and he ensured that the experience was as humiliating as possible, both for her and for himself.

The basic visual schema of

Anticipation

is alienatingly futuristic: the film’s images are tinted in red, yellow, or blue, which a mechanical voice announces as “Soviet,” “Chinese,” and “European,” respectively. At the passport control of an airport, where disembarking passengers present inspectors the palm of their right hand, one traveler, a trim man named John Demetrios (played by Jacques Charrier) presents his

left

hand and is shunted instead to a holding area, alongside a woman. Both are presented with “catalogs”—pornographic magazines with pictures of men for the woman and of women for the man. The woman makes a “selection” and is led away. Moments later, the man does the same and is led to a hotel room by a bellhop (played by Jean-Pierre Léaud), who plugs in a light fixture and sets up a row of aerosol cans on a dresser.

Shortly thereafter, an official knocks on the man’s door and greets him (“Honor to your ego!”) as he presents him with his selection: a dark-haired, silent woman wearing a dress held on by thin chains bolted to a metal neck-band. John invites her into his room; there, she hands him a series of wrenches to undo the bolts and remove her dress. Topless, she enters the bathroom, from which she emerges fully nude. She gets into bed, and John joins her there, asking her in a halting voice, with unnatural pauses between syllables, whether she speaks. When he finds that she does not, he calls the official and complains that she does not arouse him. The official brings him another woman: it is Anna Karina, decked out in a long, old-fashioned ruffled white dress.

Karina—who identifies herself as Eléonore Roméovitch—enters and greets him: “Honor to your ego.” John asks, “You can speak?” She says, “Of course I speak” (the line from the ending of Jerry Lewis’s

The Bellboy

), “that’s what I’m here for.” He asks her whether she is thirsty, and she requests Evian. He takes an aerosol can of Evian from the dresser and sprays her face with it. In close-up, Karina’s face is being sprayed copiously wet at point-blank range: her mouth is open wide, her eyes are closed, and her tongue is agitating

lasciviously to drink the fluid. It is Godard’s most obscene and degrading shot to date, showing the cruel subjection of a woman, with her face sprayed as if with sperm or urine, which the actress is lapping up avidly. It is a view of Godard’s readiness both to humiliate Karina and to show her in a state of carnal abasement—to a man who is not him. (He follows it with a shot of Eléonore subjecting John to the same treatment.)

John Demetrios orders her, the verbal prostitute, to undress. She responds with vehemence, “I won’t get undressed”—the line with which Godard’s acquaintance with Karina began, in 1959, when he offered her a part in

Breathless

that she rejected. She explains her refusal in a strange dialogue:

E

LÉONORE

: Everything is specialized today… It may seem outdated. On Earth it’s considered a very modern idea. Thousands of people have fought for it and died for it.

J

OHN

: What idea?

E

LÉONORE

: Integral specialization. For example, as for me, I don’t get undressed. Prostitutes who get naked, that’s physical love. They know all the gestures of love.

J

OHN

: And you?

E

LÉONORE

: I know all the words. I am sentimental love.

J

OHN

: Love in language.

Godard, through Karina, condemns precisely the type of film in which he had dramatized love: there are, in effect, two cinemas, one of words, of sentimental love, in which respected actresses like Anna Karina merely talk but stay dressed and do not show the act of love, and the other of gestures, in which people get undressed and do show the act—that is, the pornographic or erotic cinema.

Eléonore strums an oversized comb like a lyre and recites fragments of the Song of Songs (“my breasts are like little gazelles”) but again, John declares himself not aroused because although she speaks she does not accompany her words with gestures. She complains, “You can’t have both together. It’s only logical. I can’t speak with my legs, my bosom, my eyes.” Pensively stretched out on the bed, John comes up with an idea: “There is one part…” and Eléonore picks up the thread. “One part of the body which talks and moves at the same time. But which?” He points to her mouth, and she understands: “In putting the mouths one upon the other, we will speak and move together at the same time.” Upon hearing this innovation, an electronic surveillance voice blares, “The prostitute in room 730 is discovering something: language and pleasure at the same time.” The couple

bring their lips together; in a close-up, they kiss; in an extreme close-up, they kiss again, and the loudspeaker voice emits an anguished machine-cry, “Negative! Negative! Negative!”—Godard’s horrified vision of Karina kissing another man. But the image itself is positive: each time the lips touch, the harsh blue color filtration is gone, replaced by natural color and its glorious bloom on Karina’s face. She faces the camera with a challenging look of demure satisfaction, a declaration of innocent pleasure, and smiles. Superimposition: the word

fin

(the end). End of film; end of filming Anna Karina.

W

HEN

T

WO OR

T

HREE

T

HINGS

opened, on March 18, 1967, the reviews broke predictably, with the periodicals that served Godard’s own “little audience” exalting it. The film was the cover story of

Le Nouvel Observateur

, and Jean Collet of

Télérama

recognized it as “a painful confession, a contained rage, an anguished reflection”

60

—but it didn’t matter. Godard was already off in another direction, which he explained in an interview at the end of 1966.

Q: What is your new film?

A:

La Chinoise

.

Q: What will

La Chinoise

be?

A: A female student who reads Mao Zedong.

Q: French?

A: Yes.

Q: Played by whom?

A: I haven’t decided yet.

Q: Have you read Mao?

A: [No response.]

61

Michel Delahaye of

Cahiers

saw where Godard was heading:

Let us note here that the year’ 66 (which goes from

Masculine Feminine

to 2 or 3) is precisely the year when the world began to take notice of certain messages… of the demands of youth, and youth of its own demands. What they want: the death of this civilization—of which, for better or worse, the USA is the last bastion.

62

Godard did not come to this younger generation on his own. Rather, he came to it by default. Had he married Marina Vlady, he would also have married into her family: into relations with her children and parents and siblings in and around their teeming dacha. He would have married himself into a social role of adulthood that had escaped him until then. Vlady’s rejection of

him also propelled him out of such a well-charted orbit and into a world of young people with new ideas, indeed of young people whose youth itself was an ideology. In effect, she pushed him into the arms of Anne Wiazemsky, and into the radically different life—and cinema—that resulted. Cinematically and romantically, Godard was starting from zero; like one dispossessed, he would make a leap of faith into an absolute and totalizing doctrine that seemed to answer with hope and with certainty his despair and his doubt.

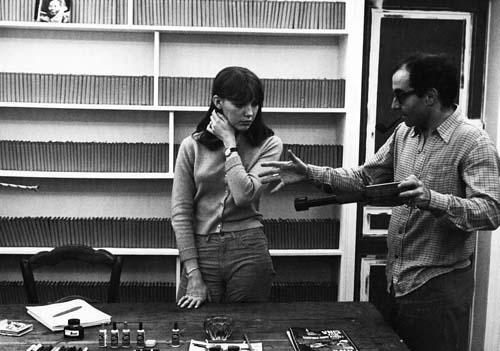

Hundreds of Little Red Books and a toy weapon

(Pennebaker Films / Photofest)