Evolution's Captain (16 page)

Read Evolution's Captain Online

Authors: Peter Nichols

Â

FitzRoy abandoned the attempt to reach March Harbour in the

Beagle

. Days of continued bad weather forced them north and east through Nassau Bay, still farther away, until he finally decided to leave the ship in Goree Road, a secure and accessible anchorage atop Nassau Bay, and proceed in the smaller boats through the inside passages among the islands to the area around Christmas Sound.

But York Minster stopped him. He told the captain he didn't

want to return to his own country. He and Fuegia, his wife to be, preferred to settle with Jemmy Button and Matthews in Jemmy's “country,” York told the captain. FitzRoy was surprised but glad. He thought it much better that the three of them and Matthews all settle together.

“I little thought,” he later wrote, “how deep a scheme Master York had in contemplation.”

D

arwin was among the large group that set out on January

19, headed for the place near Murray Narrows that Jemmy Button called his “conetree,” from where he had first been taken. This was where FitzRoy now decided the new settlement and mission should be established.

For about a day, he had considered the land on Lennox and Navarin Islands around the

Beagle

's anchorage in Goree Road. More towns and cities have come into being because of their proximity to a safe harbor than for any other reason. The coast hereabouts was unusually flat for this drowned-mountain region, and FitzRoy thought it might prove suitable to agriculture. But after tramping across it for a few miles with Darwin, they found the whole area to be a swamp, “a dreary morassâ¦quite unfit for our purposes.” Jemmy's country, where he was keen to return, seemed more promising.

FitzRoy, Darwin, Matthews and the three Fuegians, Bynoe, the

Beagle

's surgeon, and about twenty-seven seamen, marines, and officers, filled three whaleboats and the ship's 26-foot yawl. Temporarily decked over, the yawl was also crammed with the cargo largely donated by the Church Missionary Society and others to start the Fuegians and Matthews on their new life.

The choice of articles [wrote Darwin] showed the most culpable folly & negligence. Wine glasses, butter-bolts, tea-trays, soup turins, [a] mahogany dressing case, fine white linen, beavor hats & an endless variety of similar things shows how little was thought about the country where they were going to. The means absolutely wasted on such things would have purchased an immense stock of really useful articles.

The folly and the culpability were mainly FitzRoy's, as Darwin surely knew. The captain, better than any of the well-meaning donors, knew the conditions of the wild, uttermost shores upon which the pioneers would be deposited. He had apparently not instructed the generous suppliers on what might have been more useful, nor sold or traded the linens, tea trays, and beaver hats for tools. He had been the prop master organizing the shipping and handling of all these silly items. He had watched them being carried into the

Beagle

's hold at Devonport, where they had taken up valuable cargo space. It was one thing to have the queen of England presenting Fuegia Basket with a ring as a keepsake from a famous patron, but something else altogether to transport a boatload of genteel and mainly useless bric-a-brac to Tierra del Fuego. What could he have been thinking?

Here was the crazy myopia of FitzRoy's vision, fueled and abetted by Britain's expansionist aspirations and its own special relationship with God: three little wigwams raised against the williwaws of Cape Horn, each fixed up inside as an English drawing room, in which York, Jemmy, and Fuegia would repose, in their tailcoats and cravats and bonnet, with Matthews in the third wigwam to lead them in Sunday services. If such a thing was possible, what might not have grown from it? This was FitzRoy's dream, and he had pursued it with the energy of Alexander.

The boats traveled north from Goree Road and entered the Beagle Channel. This remarkable, two- to three-mile-wide, nearly straight, easily navigable waterway running east-west for 120

miles between high mountains, had been discovered by Murray, the

Beagle

's master on the previous voyage.

Darwin's doubts about the venture didn't prevent him from enjoying the outing or the constantly magnificent scenery.

In our little fleet we glided along, till we found in the evening a corner snugly concealed by small islands.âHere we pitched out tents & lighted our fires.ânothing could look more romantic than this scene.âthe glassy water of the cove & the boats at anchor; the tents supported by the oars & the smoke curling up the wooded valley formed a picture of quiet & retirement.

It was like a camping scene by the American painter-franchiser Thomas Kincaid, whose lurid sublimity and mossy palette would be just right for the exaggerated picturesqueness of Tierra del Fuego.

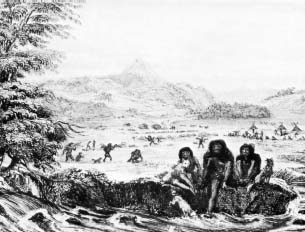

As the group pulled west along the channel the next day, Fuegians appeared on the shore. They gaped at the cruisers in astonishment and ran for miles beside the channel to keep up with the boats. The Beagle Channel does not appear to have been noticed by voyagers before Murray came upon it in 1830; it would have been out of the way and unknown to the sealing and whaling vessels that frequented the region's ocean coasts or the Strait of Magellan, so it's probable that many of the Fuegians who saw the Englishmen in their boats that day had never seen any but their own people before. Fires sprang up all along the coast, both to attract the strangers' attention and to spread the news of their presence. For Darwin, the Fuegians delivered another gothic-opera spectacle:

I shall never forget how savage & wild one group was.âFour or five men suddenly appeared on a cliff near us.âthey were absolutely naked & with long streaming hair; springing from the ground & waving their arms around their heads, they sent forth the most hideous yells. Their appearance was so strange, that it was scarcely like that of earthly inhabitants.

The Anglicized Fuegians traveling with the Englishmen thought no better of these people than the group they had met a few weeks earlier in Good Success Bay. “Large monkeys,” York Minster called them, laughing at them with what to FitzRoy must have been a dispiriting lack of Christian feeling. (Since there were no monkeys in Tierra del Fuego, York could only have acquired this derogatory comparison in England, and it's not hard to imagine how.) Jemmy Button assured the captain that these people were greatly inferior to his own, who were “very good and very clean.”

It was Fuegia Basket who had the strongest reaction to the sight of her countrymen in their original stateâher first in two and a half years, since she hadn't come ashore with the others at Good Success Bay. She was plainly terrified. After two years of total immersion among the most fragrant of English sensibilities, she was shocked at their nakedness and brute appearance. She may also have felt an acute embarrassment: this was who and what she really was. She had been lifted out of this, taken to another world and given the profoundest makeover. But now she was being returned to starkest heathendomâit is nowhere recorded whether she was pleased to come back or notâto be left here with a chest full of dresses and petticoats, some tea trays, and her great hulking twenty-eight-year-old suitor York Minster. Fuegia was still only twelve years old at the most, an intuitive, clever girl to be sure. But such attributes may not have helped her at this moment, when dumb ignorance might have been preferable. Her grasp of all that had happened to her, and was about to, can only be guessed at. FitzRoy, with his tunnel vision, so ready to believe what he wanted to believe, is our only witness to her feelings. He wrote: “Fuegia was shocked and ashamed; she hid herself, and would not look at them [the wailing wild men ashore] a second time.”

Two days farther westward along the Beagle Channel, the convoy passed below what is now the port of Ushuaia. That evening, in a cove at the north end of the Murray Narrows, they met a small

group of “Tekeenica” Fuegians. They were members of Jemmy Button's tribe, whom he remembered, and they remembered him.

Both FitzRoy, and therefore Darwin and others, described Jemmy's tribe as the Yapoo Tekeenica, or the Yapoo division of the Tekeenica tribe. It's not clear where FitzRoy got this, though he wrote that he believed he had heard Boat Memory and York Minster referring to the Fuegians of this area as Yapoos on the previous voyage. But he was mistaken. The tribe, and Jemmy Button, actually called themselves Yamana. Lucas Bridges, son of the missionary Thomas Bridges, who later established a mission at Ushuaia and produced a 32,000-word Yamana-English dictionary, explained such a misunderstanding in his book

Uttermost Part of the Earth

.

It is interesting to note how many names have arisen through mistakes and even become permanent by finding their way into Admiralty charts. Early historians tell us of a place called Yaapooh, and speak of the people of that country. No such place or people existed, and this word is simply a corruption of the Yaghan [Yamana] name for otter,

iapooh

. No doubt FitzRoy, pointing towards a distant shore, asked what it was called. The [Fuegian's] keen eyes would spy an otter, and he would answer with the word, “Iapooh.”

In all the charts of this countryâboth Spanish and Englishâa certain sound in Hoste Island bears the name Tekenika. The Indians had no such name for that or any other place, but the word in the Yaghan tongue means “difficult or awkward to see or understand.” No doubt the bay was pointed out to a native, who, when asked the name of it, answered, “Teke uneka,” implying, “I don't understand what you mean,” and down went the name “Tekenika.”

Much of what FitzRoy “learned” from his dealings with Fuegians must be set against misunderstandings like thisâand his reliance on translators who were frequently under coercion.

Although they were his people, Jemmy found he had forgotten much of his native language and had trouble understanding them. York Minster, though from another tribe, did better and acted as a translator. In this way, Jemmy heard the news that his father had died. He had already had a “dream in his head” to that effect, wrote Darwin, so he seemed unsurprised, but according to FitzRoy, he looked “grave” at this news, went and found some green branches, which he burned with a solemn look. After that, he returned to his usual, cheerful self.

In the morning, a large number of natives arrived at the cove as the Englishmen were breaking camp. Many had run so fast over the mountains from Woollya (now Wulaia) that blood was streaming from their noses. Their mouths foamed as they talked, feverishly lobbing questions at Jemmy and the others. Bleeding, frothing at the mouth, gasping for breath, painted white, red, and black, they looked like “so many demoniacs” according to Darwin.

These were all “Tekeenicas,” natives of southeastern Tierra del Fuego according to FitzRoy, who believed he saw marked differences between them and other Fuegians. These were

low in stature, ill-looking, and badly proportioned. Their colour is that of very old mahogany, or rather between dark copper, and bronze. The trunk of the body is large, in proportion to their cramped and rather crooked limbs. Their rough, coarse, and extremely dirty black hair half hides yet heightens a villanous expression of the worst description of savage features.

This is FitzRoy's standard description of all Fuegians in the wild, no matter where he saw them. It was how he saw the ungodly savage anywhere. It fitted not only his own drawing of Jemmy Button, a “Tekeenica,” after the ameliorating influences of his stay in England had worn off and left his features coarsened as of old, but also his later drawings of Maoris in New Zealand, whose lips curl threateningly and whose expressions

are uniformly villainous. “Satires upon mankind” was FitzRoy's summing up of the physiognomy of Tekeenica men. He was no more generous with the women.

They are short, with bodies largely out of proportion to their height; their features, especially those of the old, are scarcely less disagreeable than the repulsive ones of these men. About four feet and some inches is the stature of these she-Fuegiansâby courtesy called women.

As the Englishmen's convoy got underway, they were joined by more natives on the water.

In a very short time there were thirty or forty canoes in our train, each full of natives, each with a column of blue smoke rising from the fire amidships, and almost all the men in them shouting at the full power of their deep sonorous voices. As we pursued a winding course around the bases of high rocks or between islets covered with wood, continual additions were made to our attendents; and the day being very fine, without a breeze to ruffle the water, it was a scene which carried one's thoughts to the South Sea Islands, but in Tierra del Fuego almost appeared like a dream.

So this flotilla passed through the Murray Narrows to Woollya, the place where Jemmy Button had first been taken from a canoe. As they reached Ponsonby Sound at the southern end of the narrows, Jemmy recognized where he was. He now guided the boats into the quiet cove where he had once lived. There were only a few natives ashore. The women ran away, the remaining men nervously watched the boats land.

FitzRoy was immediately happy with the look of the place.

Rising gently from the waterside, there [were] considerable spaces of clear pasture land, well-watered by brooks, and backed by hills

of moderate height, where we afterwards found woods of the finest timber trees in the country. Rich grass and some beautiful flowers, which none of us had ever seen, pleased us when we landed, and augured well for the growth of our garden seeds.

The English sailors pulled hard to stay ahead of the following canoes. As soon as they were ashore, the marines marked a boundary line on the ground with spades and spaced themselves out to guard the enclosed site on which the seamen now set to work erecting the settlement's wigwams and digging a garden. The canoes began arriving, and more natives gathered on the shore. York and Jemmy were kept busy explaining to them the meaning of the boundary line, and what was happening, and the natives squatted down to watch.