Exuberance: The Passion for Life (30 page)

Read Exuberance: The Passion for Life Online

Authors: Kay Redfield Jamison

Payne is a great advocate for science: “

Happy fishermen,” she says of herself and her fellow biologists, “we stand together on the pier casting and reeling, mesmerized by a certain shimmer visible from this or that angle, enchanted by the concentric rings here and there, imagining things just below the dimpled surface. If something leaps into the air, we all lift eyebrows together as if we were one great being with one eyebrow—

that?

Is it alone, or part of a school? What else lies below?”

When I asked Payne about exuberance, she replied: “Moods in general, and exuberance as a stage in a mood, play a huge role in my life as a biologist as well as in the rest of my life.” She defines exuberance as “part of a continuum (enthusiasm—exuberance—ecstasy) and I [see] my life as a biologist as part of a continuum that includes the artistic side of my life as well: for an observer, the two are inseparable. The moment of intense observation of any kind of truth or beauty is a peak experience: I sense myself as a part of what I am seeing, hearing, feeling, smelling and therefore have no doubts about it; all boundaries evaporate and all desire for control, which is after all irrelevant when one is living the truth. Part of why I love reality is that I know that nobody can ever understand it fully … the full answer is never at hand: everything is always

evolving … my favorite feelings about what is unknown stem in part from this sense of beauty, and of the presence of steady, life-giving things around me, and these in turn stem partly from the river of happiness in which I am fortunate enough to swim at times. I really understand why people with manic-depressive illness don’t want to curb the flow … the definition of illness must be arbitrary in any case, because the value of moods also has its continuum.”

Payne describes the psychological experience of exuberance as a progression from active intoxication to a more transcendent peacefulness. Initially, she says, she feels “[h]igh, energetic. Excited. Passionate. Uninhibited. Garrulous if with someone else, ecstatic if alone.” The exuberance progresses into “a state of serenity, during which I especially like to be alone—to lie in a hammock looking up into the leaves or stars, thinking and glorying and giving thanks for the wholeness and beauty of life.”

Joyce Poole, the scientific director of the Amboseli Elephant Research Project in Kenya, is a colleague of Katy Payne’s and, like her, an excellent writer. She has been a field biologist for nearly thirty years and has made key contributions to our understanding of elephants, including pioneering research on musth (behavior which is marked, in males, by high levels of testosterone and secretions from the temporal gland). She has also studied elephant feeding, reproductive, and social behavior; their vocal and olfactory communication patterns; the effects of poaching on the social structure of elephant families; and elephant genetics. An American who fell in love with Africa when her father was director of the Africa Peace Corps program, she was, she writes, an emotional child “quick to laughter, but also quick to anger and easily wounded and saddened. With my father’s spirit of adventure and sense of principle and my mother’s emotions, I frequently became deeply upset by the injustices of life.”

While Poole was still a graduate student at the University of

Cambridge, her research on musth was acknowledged by a major award from the American Society of Mammologists and published in

Nature

. She finished her dissertation in record time because, as she put it, “

I went into an intensely manic state, working until 2:00 a.m. most mornings and returning to the office again at 6:00 a.m.” Poole took her formidable energy and scientific abilities back to Africa, where she became a consultant to the World Bank and the African Wildlife Foundation. In the early 1990s she was the coordinator of the Elephants Programme, working directly under Dr. Richard Leakey, for the Kenya Wildlife Service. Her ongoing research with Cynthia Moss in the Amboseli National Park, the longest study of wild elephants ever undertaken, follows the lives of more than a thousand individual animals.

Like many scientists, Poole describes her work as all-absorbing: “

Cynthia and I spent the long days watching elephants and the evenings recounting elephant gossip by candlelight,” she writes. “It was like reading a long novel that you don’t want to end. I became so engrossed in the elephants’ lives that on Sundays, when it was my duty to guard the camp, I used to will them to take the day off, too, so that I wouldn’t miss any important events in their lives.”

She remains transfixed by elephants: “

What do elephants think about?” she asks. “What kind of emotions do they experience? Can they anticipate the future? Do they contemplate the past? Do they have a sense of self? A sense of humor? An understanding of death?” Other elephant people, she says, “suspect I believe I am, in fact, an elephant. In some ways, perhaps, they are right. Like Africa, the elephants take hold of your spirit.” In her wonderful memoir,

Coming of Age with Elephants

, Poole’s final acknowledgment is to the elephants she has studied over the years, “

for giving me a life of meaning and days of joy.” A delight in their company and an anguish in their destruction is palpable in her writing.

When I asked Poole which experiences from her work had

given her the greatest sense of exuberance, she replied: “Well, certainly the major discoveries that I have made give me, still, a great sense of buoyant and exuberant feelings. But also the day-to-day new ideas, or the recurrence of old ideas, about why elephants do the things they do, and their development into a plausible theory, give me a sense of exuberance. Some days I have none of these feelings; other days I may feel carried along by a fast-flowing stream of exciting ideas.”

Sometimes something as simple as being able to identify a particular elephant at a distance of two kilometers will trigger a momentary sense of exuberance, she says, or being able to calm an attacking elephant by simply using her voice. The exuberance of being in the presence of elephants themselves is infectious. Poole describes the physical and psychological state of exuberance in vivid terms, with the observational eye of a good scientist. “I feel a rush of what I think of as adrenaline,” she says. “I think rapidly, thoughts falling one over the other so fast that I can hardly keep up. My heart feels as though it is beating faster. Sometimes my body almost trembles with excitement. For some reason I am very aware of my hands and fingers—a tingling sensation in my body that seems concentrated there—perhaps this is because often I am writing or driving and so my hands are the ‘doing’ part of my body in these situations and therefore I am more aware of them. I am totally ‘in the moment,’ completely focused, effervescent, buzzing, bubbling, high, on top of the world, I can do anything. I CAN.”

Like the scientists who study creativity and wonder whether creativity leads to exultation or exultation propels creative work, Poole is uncertain about the relationship between moods and imagination. “It is hard to say what triggers what,” she observes of the overlap between her exuberance and times of discovery. “Do I have a glimmer of a good idea, and that stimulates the exuberance that is so associated with the initial ‘spark’ and the development of

the idea? Or am I already in a creative phase when the glimmer of an idea strikes and the ‘exuberance’ flows? I don’t know.”

Hope Ryden, who studies and writes about many animals—among them coyotes, mustangs, bobcats, and beavers—distinguishes between the more energetic moments of joy she experiences at times of creativity and discovery and the quiet pleasure she feels when observing animals in the wild. “Of course,” she says, “

my response to what I see must be quiet, so as not to disturb my subjects.… Much of what I do is wait for something to happen, and exuberance is not compatible with that inactivity. When the action begins, however, I do feel a surge of excitement that is akin to exuberance. Nevertheless, when the animals learn to tolerate me and go about their business, my emotions settle and I watch quietly. What I feel, as I note odd bits of animal behavior, might best be described as enchantment and pleasurable empathy for my subjects who are so busily engaged in their struggle for survival.”

The quiet mood can change abruptly, however: “I experience moments of exuberance when I see something never before recorded, or when I see something that contradicts a prevalent notion that has long been accepted as fact. At such times my competitive nature asserts itself and I feel jubilant.” She feels that exuberance, as she experiences it—“a pleasurable upwelling of excitement, a speeding up of thought and action”—is not generally useful to her in the field. “While in this state,” she explains, “the photographs I take are likely to be over- or underexposed or I may fail to notice that the film isn’t properly threaded in my camera and so is not taking up. A little exuberance, while a highly pleasurable state, goes a long way for me. Mostly I try to tamp it down to something more like the pleasurable absorption I felt as a child while engaged in certain activities, such as building a sand castle. I have to conclude that watching wildlife is like play. The child in me loves to do it.”

• • •

Science is beholden to the exuberance and curiosity typically associated with the adventurous spirit of childhood, and owes its furtherance to the temperamental quirks of individual scientists. James Watson, speaking at the Nobel Prize ceremonies in 1962, ended his remarks by talking about the human side of science:

Good science as a way of life is sometimes difficult. It often is hard to have confidence that you really know where the future lies. We must thus believe strongly in our ideas, often to the point where they may seem tiresome and bothersome and even arrogant to our colleagues. I knew many people, at least when I was young, who thought I was quite unbearable. Some also thought Maurice was very strange, and others, including myself, thought that Francis was at times difficult. Fortunately we were working among wise and tolerant people who understood the spirit of scientific discovery and the conditions necessary for its generation. I feel that it is very important, especially for us so singularly honored, to remember that science does not stand by itself, but is the creation of very human people. We must continue to work in the humane spirit in which we were fortunate to grow up. If so, we shall help insure that our science continues and that our civilization will prevail.

We are beholden to the human side and enthusiasm of scientists; their passion in the pursuit of reason is heady and requisite stuff indeed.

R

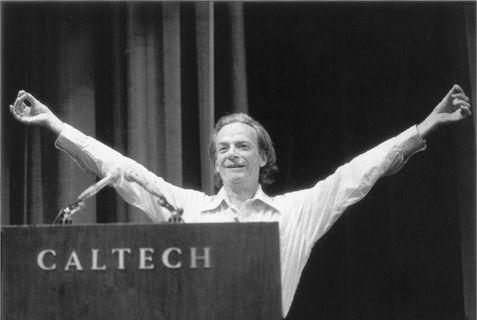

ichard Feynman depressed, observed a colleague, was “

just a little more cheerful than any other person when exuberant.” He was, as well, a preternaturally original thinker, irrepressibly curious, and one of the great teachers in the history of science. For me, Feynman’s legendary brilliance as a teacher is his most remarkable legacy, but then I am prejudiced. My grandmother, mother, aunt, and sister were teachers, and almost everyone else in the family—my grandfather, my father, an aunt, a great-uncle, a nephew, three cousins, my brother, and I—are, or were, professors. To teach well, I heard early and often, is to make a difference. To teach unusually well is to create magic.

It is a magic often rooted in exuberance. Great teachers infect others with their delight in ideas, and such joy, as we have seen—whether it is sparked by teaching or through play, by music, or during the course of an experiment—alerts and intensifies the brain, making it a more teeming and generative place. Intense emotion also makes it more likely that experience will be etched into memory.

Horror certainly does. We remember with too much clarity where we were and what we were doing when we first saw the hijacked planes fly into the World Trade Center and then, minutes later, as yet another crashed into the outer wall of the Pentagon. No one who saw this will forget. But joy, differently, also registers. We recollect moments of great pleasure and discovery—watching on a remarkable July night as the spider-legged lunar module dropped onto the moon’s surface, for instance, or listening for the first time to Beethoven’s

Missa Solemnis;

falling in love; playing through the long evenings of childhood summers—for nature has supplied us with the means to absorb the essential and to recall the critical. Teachers are among the earliest and most powerful of these means of knowing.

To teach is to show, and to show persuasively demands an active and enthusiastic guide. This must always have been so. Emotional disengagement in the ancient world would have been catastrophic if the young were to learn how to hunt, how to plant, and how to track the stars. The stakes were high: to motivate their wards would have been requisite for the first teachers—the parents and shamans, the priests and the tribal elders. Passing on knowledge about the behavior of the natural world from the emerging sciences of astronomy, agriculture, and medicine would have been among a society’s first priorities. The great natural scientists, such as Hippocrates and Aristotle, Lucretius and Hipparchus, not only studied the ways of man and of the heavens but also taught what

they knew to others. In turn, a few of those whom they taught observed the world in their own and slightly different ways, added to the stock of what was known, created a new understanding, and passed it on. “

All vigor is contagious,” said Emerson, “and when we see creation we also begin to create.” When we see a glimpse of creation through the eyes of an enthusiast, our imaginative response is intensified.