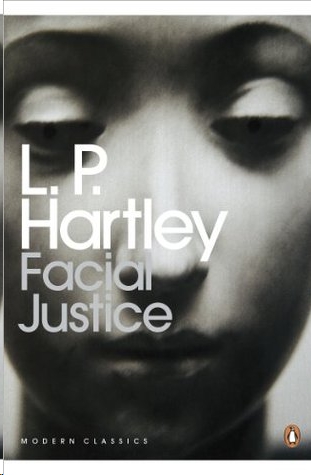

Facial Justice

Authors: L. P. Hartley

Tags: #Fiction, #General, #Science Fiction, #LIT_file, #ENGL, #novela

L. P. Hartley Facial Justice

First published in 1960

Take but degree away, untune that string, And, hark, what discord follows!

Troilus and Cressida Act I, Sc. III

DEDICATED with homage, acknowledgments, and apologies to the memory of Nathaniel Hawthorne

PART I

Chapter One

IN the not very distant future, after the Third World War, Justice had made great strides. Legal Justice, Economic Justice, Social Justice, and many other forms of justice, of which we do not even know the names, had been attained; but there still remained spheres of human relationship and activity in which Justice did not reign. Two girls were walking up the shallow curving steps of the Equalization (Faces) Center. Each was absorbed in her own thoughts; and one, to judge from an occasional twitching of the shoulders, was crying. They did not look at each other, rather, they looked away; but as they reached the top and began to converge upon the tall glass swing doors, the one who was crying fell back to let the other go in front of her. They turned and their eyes met. "Jael!" cried the one whose voice was better under control. "Judith!" They drew apart and stared at each other with looks of horror and dismay. Each felt that she was seeing her old friend for the first, and also--it simultaneously occurred to them both--for the last time. Judith saw a pretty, fair-haired girl slightly above middle height, whose mouth trembled and whose eyes were reddened by weeping. She had a faint scar on one cheek, but it did not spoil, it gave point to, her prettiness. Jael saw a dark, plain, thick-set young woman whose features were only redeemed from positive ugliness by a pleasant expression and a look of intelligence. Now, her face corrugated by bewilderment and concern for her friend, she looked a fright. Both were in their early twenties. A stranger to their world would have been struck, as they were, by the contrast in their looks, but he would have been still more surprised by something which they appeared to take for granted: the clothes that they were wearing. In each case it was a suit of sackcloth, differently cut and trimmed, but unmistakably sackcloth; and he would have noticed, with a repulsion which they did not feel, that their hair--for they wore no hats--looked dirty. Some foreign substance had lodged in it, something gray and gritty: could it be ashes? Having looked their fill the two girls dropped their eyes, as though the spectacle was too painful to look at. Judith was the first to speak. "I didn't expect to see you here, Jael," she said in a low voice. "Nor I you, Judith." For a moment this seemed all that they could say, then Judith stole another glance at her friend's swollen and tear-stained prettiness, and murmured: "I might have guessed." "But you, Judith--" began Jael, and stopped. Well as she knew Judith she could not put her thoughts into words that would not sound insulting. But Judith spoke for her. "You see, he wanted it." "Who?" "Well, Cain." "Oh, _no__." Much less upset than her friend, Judith answered steadily, and almost defensively: "Well, he's a man, after all." "So he may be, but--" She could not face the "but," but Judith could. "You mean I'm not so ugly? I was Gamma minus, you know, at my last Board." "I can't believe it," Jael said, not looking at Judith. "So I've qualified for a rise. Any Gamma is, of course, below Gamma plus." "They must be blind," cried Jael, indignantly. "I. . . I love your face, and so should he. You don't want to change it, do you?" "No, I'm used to it, you see. I'd rather have been born Beta, of course. But if he wants it--! Getting the permits was the worst part. I minded that." "You never came to me." "I went to strangers, mostly. You know, the professionals. You have to pay, of course, but you get secrecy." "Does that matter?" Jael asked. "Everyone's got to know in the end.... What... what model did you choose? Number 5?" "Oh, don't you know? There's no personal choosing now--that's been cut out, it was found to be too expensive. They choose one of three stock models. I wanted Oval, but Cain--" Judith stopped, feeling she had talked too much about herself, "likes heart-shaped best. What... What..." Judith hesitated; in her turn she was unable to put the question. She saw her friend's tears falling afresh; she knew the cause; there was really nothing to say. "I was going to choose 5," said Jael listlessly. "But now you tell me it's been canceled." "Yes, this afternoon. It was given out at three o'clock. Where were you?" "At the Litany. I always go there for my half-day. Where were you?" "I was at the Casino," Judith said. "I hadn't been for quite a long time. Actually I prefer the Litany, but it doesn't do to show a marked Personal Preference." Jael was hardly following. "I suppose not," she said. "No." Judith was firm. "It leads to inflammation of the ego. But I'm so sorry for you, Jael. Number 5 would have suited you so well. Tell me... Tell me how it happened. Of course, I'm not surprised. Everyone knew you were an Alpha--and Alpha is antisocial," she added reluctantly. "Alpha is antisocial," repeated Jael with bowed head. After a moment she went on, "I only just failed the Misses." "I know," said Judith. "That was three years ago. I've been in danger ever since. I thought that when I cut my cheek with the razor--" "Then it wasn't an accident!" exclaimed Judith. "No. I thought it would make me B--" She shrugged her shoulders. "Oh well, put me into a lower category. But I hadn't the courage to do it properly, and my next Board passed me Alpha." "What bad luck! Oh, I mustn't say that--luck is a leveler." "Luck is a leveler," repeated Jael. "And then the complaints began coming in again. The Ministry warned me yesterday that I'd had my twenty-fifth." "Were they all genuine?" "So the Ministry said. They look into them pretty carefully, you know. I'd have had thirty, but five were disallowed as frivolous." "I wonder who--" Judith began. "Oh, they don't tell you. I can guess a few, of course. Electra 50 was one, I'm sure. Maybrick 303--she's always had a down on me. And there are several more whom I suspect. That makes it so unpleasant. It might have been anybody, Judith, it might have been you." "It wasn't," Judith said. "I shouldn't really blame you if you had. They nearly all complained of E--Bad E," she added hastily. Equality and Envy--the two E's--were in the moral sphere the positive and the negative poles on which the New State rotated. The one attracted, the other repelled. Either word, once uttered, involved the speaker in a ritual dance--a few ecstatic capers for Equality, a long, intricate, and extremely ugly gymnastic exercise for Envy. Some were excused the latter on medical grounds; but both words were conversational pitfalls which most people tried to avoid. The abbreviations Good E and Bad E were recognized substitutes exempt from ritual consequences; their facetious counterparts, Good Egg and Bad Egg, likewise were immune. "Bad E," repeated Judith, disapprovingly. "It was my eyelashes they mostly picked on, for being too long and curly. My fault, of course, I should have cut them, but sometimes I forgot. One woman complained she had lost several nights' sleep just thinking about my eyelashes. She felt they were digging into her, she said." "How do you know it was a woman?" Judith asked. "It might have been a man--it might very well have been a man." "The complaints all came from women, I was told. Most men don't really mind you being pretty." "On principle they ought to," Judith said. "Yes, I suppose so." Jael was resigned. "We ought all to be e--" "Equal" she was going to say, but she bit the word off, for equality was, with envy, the most dreaded conversational booby trap that the Dictator had introduced into conversation. To get through the ensuing ritual with credit one needed the grace of a ballet dancer; indeed, the proper performance of it was taught at all dancing classes. Done well, it was a beautiful and touching _pas de deux__, but the movements had to be so precise and identical that very few could do it justice. An Inspector had the right to ask any passer-by to perform it for him--or her, for there were women Inspectors too, though not so many of them. But the right was seldom exercised, except by the more officious Inspectors. The mere fact that one person could acquit himself better than another fostered the very element of competition that the ritual was designed to discourage. "Of course, we must all be level," said Judith confidently, for the word _level__ had no ritual consequences. "All the same I have always thought"--she lowered her voice--"that we ought to be leveled up, not down." Jael said nothing. "You are quite pretty enough to be one of the Misses," Judith went on indignantly. "I can't imagine why they failed you." "On my nose," said Jael. "It's too..." "Too retroussé?" "Yes. When I was hoping to be elected I tried all sorts of things to... to lengthen it. But it was no good. Then I cut myself to be Beta--" "Beta is best," said Judith perfunctorily. "Yes, Beta is best. It's so lonely being a Failed Alpha." "Alpha is antisocial," put in Judith, but without much conviction. "Yes. Failed Alphas suspect each other. We're betwixt and between--not one thing or another. And to cause Bad E is the worst thing you can do. I shall be much happier B--" She nipped the word off, and looked through the glass doors into the circular hall in which nurses wearing white aprons over their sackcloth were passing to and fro. "I could be one of them," she said. "There are no openings for us, as you know. We can only get temporary jobs, subbing for other people. It's so restless and unsatisfactory. And yet somehow I can't reconcile myself--" "Why should you?" asked Judith, suddenly. "Why should you, Jael? It isn't compulsory." "No, but it may become so, if enough people don't volunteer.... Perhaps we'd better go in now, Judith. I'm only keeping you." Irresolutely she moved her hand toward the door. But Judith restrained her. "I don't see why you should," she exclaimed. "It's not your fault that you're an--oh, blast the word! I believe someone's pushing you into it." She looked at Jael keenly. "There! I knew I was right." "It's Joab," Jael murmured. "Don't tell anyone." "What, Joab 98? Your brother? But what's it got to do with him? Besides he's a Failed Alpha, too." "Yes, but only for brains, and it doesn't matter for men, that's what's so unfair. He's got a good job as a statistician, and he's terrifically keen on the regime, it's his religion. Being his secretary, I see a lot of him, and he's always nagging me, just as Cain, I suppose, nagged you." "I like that!" exploded Judith. "Your own brother! But all the same"--she resumed her normal voice--"if I were you I wouldn't. There are masses of other Failed Alphas about, and I don't believe that anybody envies them. It's different for me--no one will mind if they never see my face again, and I shan't either. I shall be just another Beta." "Beta is--" "Oh, cut it out. I shan't have to bother how I dress. Hats stock size, stock shape, stock color. All the shops have Bargains for Betas. You've no idea what I used to go through, trying to make the best of myself, while anyone could see I was a low Gamma. People who valued their aesthetic sense wouldn't be seen with me. Oh yes, the second letter of the alphabet is best. It won't change my nature; one's personality isn't in one's face, as some of the malcontents try to make out. I shall be the same underneath." "Shall you destroy your Gamma photographs?" asked Jael. "One is supposed to, of course. I expect I shall be glad to. It's an offense to keep them after you've been altered. I've only had one photograph taken since I was old enough to know what I really looked like and that was for my registration card. I shall have to get a new one for that, I suppose." "Will you?" said Jael. "Won't any second letter do as well? I mean, they all look alike. You can buy the photograph of a stock face off the peg." "It's like fingerprints, you know," said Judith. "Experts can tell the difference--and, and... people who know you well. And there's one's figure," she added, with a self-deprecatory giggle. "That doesn't alter." "I know," said Jael, who was busy with her own thoughts. "But Maybrick 93 always has to tell me who she is now that she's got her stock face." "She never had much individuality even when she was an antisocial," said Judith, who was better than Jael at bypassing troublesome words. "It's my belief that she had herself lowered out of vanity--people didn't mind her type of good looks all that much. Now it's different with you, Jael. If you get yourself lowered something will be lost." "Do you think so?" asked Jael, doubtfully. "I'm sure of it. And Joab's a pig to want you to." "Well, you see, he remembers the war, and he says that any sacrifice--" "We all agree to that, and we know that Excellence belongs to the Elect--" "Excellence belongs to the Elect," repeated Jael, humbly. "We mustn't try to rise above each other." "But you're not trying. You were born good-looking. It was natural--" "Nature is nasty," Jael said. "Nature is nasty," repeated Judith. "But even the Dictator--" "Darling Dictator," put in Jael quickly. "Darling Dictator, then. Even he has said that one must not be in too much of a hurry to condemn the natural. The natural, he said, is only to be condemned when it transgresses the rule of E--and you know which E I mean." Confusion between the good^ and bad E's was so frequent that some of the more devout and law-abiding members of the New State found it safer to abstain from abstract discussion. "But in my case," Jael said sadly, "nature has transgressed. That's just it." "But not too badly," Judith tried to reassure her. "You remember Article 31 of the Constitution--attributes of E--Even E--Good E--has blurred edges--we are advised not to inquire too closely where the blur ends. Well, Jael, you are the blurred edge. And in Chapter 19 of the Revised Pandects it says: 'Life is to be lived fully within the limits of the Law. A river must not be content with its bed: it must explore its banks.' " "What a memory you have," said Jael, admiringly. "I'd forgotten that one." "But it's most important. And somewhere else he says: 'Ours is not a negative philosophy; and it is not for the delinquent to have a more delicate conscience than the Dictator.'" "When did he say that?" asked Jael, obviously unconvinced. "He changes his views so often." "Not long ago. And he only changes them in matters of detail--respected be his name." "Respected be his name," echoed Jael, reverently. A nearby clock struck six. "Great Dictator! It's time for me to go in," said Judith briskly. She turned first rather red, then rather pale. "My appointment for a rise at six o'clock." "Mine, too," said Jael, beginning to tremble. "But you're not going to keep it," said Judith. "You're not going to keep it, Jael, do you hear? I... I forbid you to!" Jael's tears were beginning to flow afresh and she looked the picture of irresolution and despair. "But I'd get it all over!" she wailed. "All... all... the mental pain of making up my mind! You've no idea what I

went through! I haven't slept for nights! It was like... like deciding to die! And I _shall__ die, in a way--you won't see me again! Not the me that I am now. I know the me doesn't matter--" "The me doesn't matter," repeated Judith, in an unwilling voice. "But somehow I can't bear to lose it!" "That's what I said!" cried Judith. "You mustn't lose it! You're not to lose it! You're going beyond your orders!" Pointing to her shrinking friend she raised her voice and said, "You are transgressing Chapter 19, subsection 3, of the Revised Pandects." Jael was obviously impressed by this but she became still more agitated. "But what shall I do? How shall I face Joab? And I can't, I can't make up my mind again! Oh, how I wish I had been born Beta! And I wish I hadn't run into you here, Judith! I shouldn't have, if we hadn't both kept the dear Dictator's command to be a quarter of an hour early for every appointment! And he only gave it out last week! Oh, how miserable I am, how miserable I am!" Wringing her hands she swayed to and fro. Judith looked at her friend in concern and pity, then took a quick decision. "Go back now," she said, "and I'll explain to your Bureau that you aren't well enough to be put down. Then you can think it over quietly. I'll come in tomorrow and you'll have a good laugh when you see me Beta. The operation's hardly more than having a tooth crowned. Good-by, Jael 97. Kind thoughts of the Dictator."