Faith (22 page)

Authors: Jennifer Haigh

“I must have been asleep when it happened,” she told Mike. She hadn't actually seen it herself.

The priest had taken Aidan swimming in the ocean. High tide then, a dangerous current. Aidan had been afraid. He had clung to the priest as they swam and frolicked, and the priest had pressed up against him. The current was rough, the water empty of swimmers. Alone in the surf he'd reached into Aidan's swim trunks. He'd made Aidan reach into his. Father Art had touched her son out in the open, in front of God and everybody. And Kath had lain there sleeping, not fifty feet away.

Mike McGann was looking at her strangely. “You never reported it,” he said. “You could have called the police.”

“I fucken hate cops.”

There was a long silence.

“So it happened just that once?” Mike said slowly. “That one time in the water?”

“Yeah, I guess. Isn't that enough?”

He released her hand quickly, as though it burned him. “I have to go,” he said.

W

hat thoughts ran through Mike's head as he roared across the South Shore, flouting local speed limits, racing up the ramp to the empty interstate on the first dark hour of a Tuesday morning? He'd found the KeySpan envelope in his glove box, Art's address written in Ma's neat hand.

His brother was afraid of the water. More than afraid: Art was terrified. Mike himself was a fearless swimmer, a skilled surfer. His whole life he had viewed his brother with disdain. In all his years as a lifeguard he had never seen anyone so pathetic: a grown man skittish even while wading, who jumped back like a little girl if the water rose above his ankles.

Art swimming at high tide, clutching a fifty-pound child?

Art groping the boy while the surf rose around his shoulders?

He had done

nothing of the kind.

Mike drove fiercely that night, the rage nearly blinding him. It had taken all he had to walk out of Kath Conlon's apartment. He could have shaken her, strangled her, killed her with his bare hands. Never in his life had he exercised such self-control.

You're a fucken liar

. He hadn't said it, didn't need to. Kath Conlon no longer mattered. She wasn't worth his time.

Green highway signs flew past. Grantham, Weymouth, Abington, Braintreeâa maze of suburbs Mike navigated without thinking. For eight years he had sold real estate; he carried in his head a detailed street map of the entire South Shore.

Dover Court was silent when he arrived, the front lawn illuminated by floodlights, the parking lot bright as day. Mike pulled into a visitor's space in front of the office. As he approached the A building he saw the flyer posted on the front door.

HAVE YOU SEEN THIS MAN?

Art's face circled in fat black marker, subtle as a bull's-eye.

“Motherfucker,” Mike muttered.

He jogged up the stairs to Art's apartment, his shoes loud on the metal rungs. He didn't care if he woke the whole building. He knocked at Art's door.

I'm sorry, man. Can you ever forgive me?

He knocked again, glanced at his watch. Art was asleep, had to be. Where did a priest go at one in the morning?

“Art. Open up.”

Across the hall a door opened. A big red-haired guy stood there in a bathrobe, squinting. “Keep it down, will you?”

“I'm looking for your neighbor,” said Mike. “Have you seen him?”

“He's gone,” the guy said.

“Gone where?”

He shrugged. “The hospital, I guess. The ambulance came a couple hours ago.”

“Ambulance?”

Mike stared in disbelief. “What happened?”

“Beats me,” the man said.

Mike ran a hand over his head. “Can you at least tell me what hospital?”

The guy tightened the belt of his robe. “I could give a shit. Fucking degenerate. Liar, too. I hope he dies, you want to know the truth.”

Mike felt the rage fill him like liquid, flowing into every corner. “That's my brother,” he said evenly.

“Congratulations. You must be proud.”

He was a big man, nearly Mike's size, but groggy and unprepared. Mike charged like a bull.

T

HE EMERGENCY

room was busy for a Monday night. Two lone women on opposite ends of the waiting room, domestics probably. An old man waiting, reading a newspaper. A Muslim woman in a headscarf, holding a fussy baby. She looked up periodically to scold three little girls who chased each other around the room.

Mike approached the reception desk, clutching his right hand. The soreness was deeply satisfying. He hadn't hit anyone in years.

Behind the desk sat a large black woman in a colorful smock. She eyed Mike's hand. “Your name, please.”

“Mike McGann. But I'm not here for myself. This is nothing.” He shoved the bruised hand into his pocket. “My brother came in on an ambulance. Arthur Breen.”

“Have a seat, please.”

“Can you just tell meâ”

“Have a seat, sir.”

Mike felt a hand on his back.

“Hey. McGann, right?”

Mike turned. The guy was his own age, vaguely familiar. He wore the standard EMT uniform, black pants and blue shirt, and a name tag:

KELLY

. He offered his hand.

“Been a few years, man. I heard you left the force. How you been?”

“Hey, Kelly.” Mike glanced over his shoulder. The black woman had left the desk. “Help me out here. My brother came in on an ambo. South side of Braintree. His name is Art Breen.”

Kelly's eyebrows shot up. “That was your brother?”

“Yeah,” Mike said warily, remembering the headlines, Art's face in the newspaper:

DO YOU KNOW THIS MAN?

“Dude, I brought him in. An OD. Some kind of pills. We couldn't find a bottle.”

Overdose?

Art?

Mike stared at him, not comprehending. “Are you sure?”

“He wasn't breathing,” said Kelly. “I had to intubate.”

Mike thought: This is not possible.

“A priest was there with him,” said Kelly. “We defibbed and got here as quick as we could.”

“OD,” Mike said. “Are you sure? It couldn't have beenâa heart attack, or something?” He lowered his voice. “He's been under a lot of stress.”

If Kelly caught his meaning, he gave no indication. “Look, I'm not saying it was intentional. Some kind of drug interaction, maybe. Was he taking any medication?”

“Art? He's in perfect health, far as I know.”

Kelly frowned. “This is kind of weird. When I opened his shirt, I saw marks on his chest.”

“Marks,” Mike repeated. “Tattoos?”

“Nah. Some kind of medical marking. For surgery, maybe. Was he in the hospital recently?”

“Mr. McGann.”

Mike turned. The black woman stood at the desk.

Kelly offered Mike his hand. “Good luck, man. I hope he pulls through.”

Me, too

, Mike thought.

B

enedicamus Domino.

Deo Gratias.

A

RT HAD

risen early that morning, an old habit. For weeks he'd slept poorly, wandering through the days in a trance of exhaustion. Yet even in that state, his internal clock was unforgiving. His eyes snapped open at six o'clock without fail.

He longed for sleep the way a man longs for a woman, a yearning that would not abate, a need unsatisfied by prayer. For most of his life he'd been spared both hungers. He had slept easily. He had not longed. He understood, too late, that he had lived in a blessed state, innocence or ignorance; a state to which he would gladly return.

But time, the engine of the physical world, moved in one direction only; there was no reversing it. Would he have done so, if it were possible? Would he have given back the last year of his life, his

annus mirabilis

, its exhilaration and sweetness? Were the piercing joys at least equal to the dark miseries, despair and shame?

It was a frivolous question, predicated on fantasy. Time would not change course, not for anyone. Certainly not for Arthur Breen.

â¢Â  â¢Â  â¢

H

E BEGAN

that day in his usual fashion, at the public library. According to a librarian I asked, he was waiting in the parking lot each morning when the place opened at nine. She couldn't tell me which books he checked out, just that he spent hours poring over foreign newspapers, French and Italian.

“That stuck in my mind. I was glad to see someone read them,” she said.

No

Globe

, then, for my brother; no

Herald.

No lurid headlines condemning the Cardinal, the Archdiocese, the dozens of priest in disgrace. I imagine him at the long table beneath the sunny window, hunched over the

Corriere della Sera

, his reading glasses sliding down his nose. Art taking a last look at the world, the parts of it he loved the most.

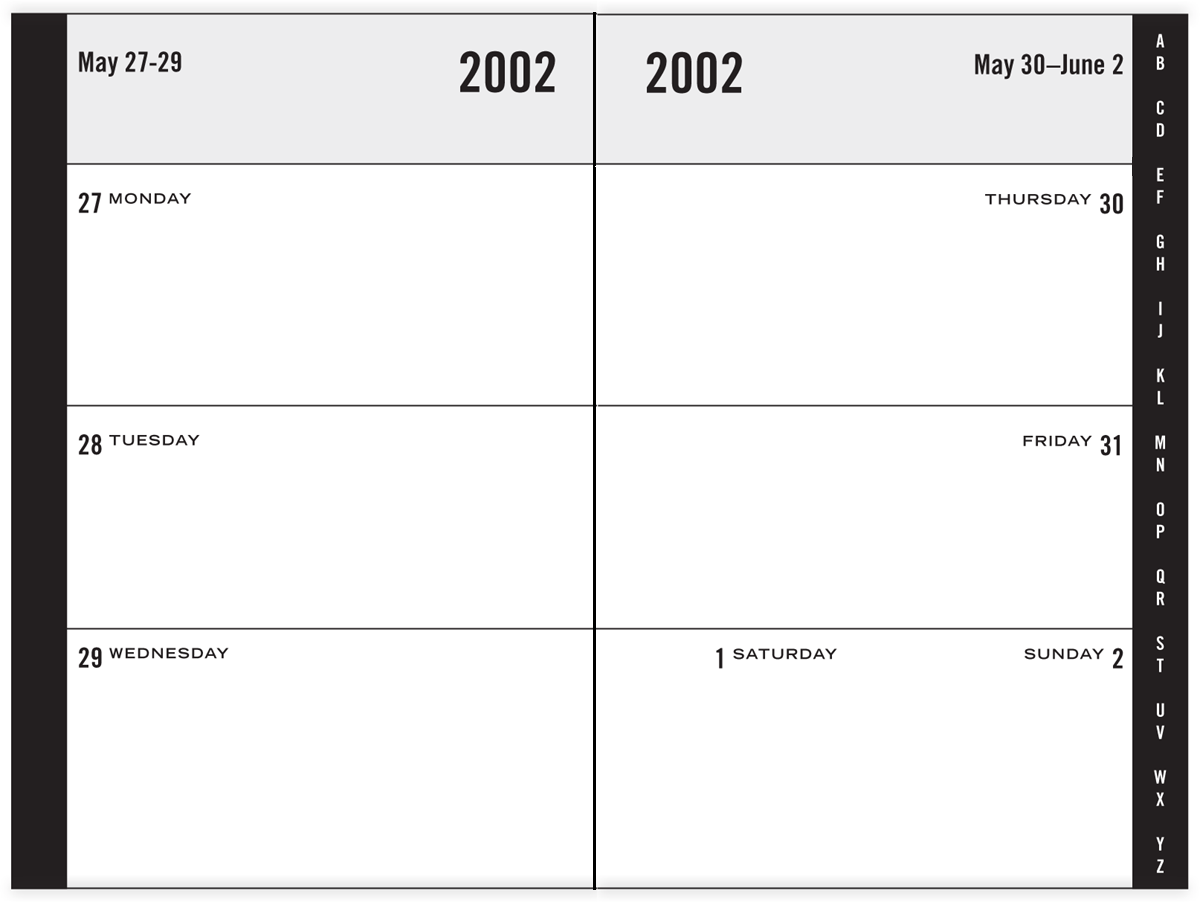

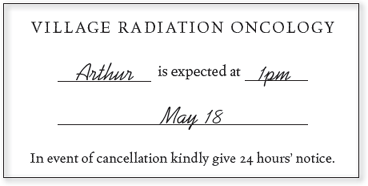

He left the library at ten-thirty. Where he went next, I can't say. The final pages in his datebook were left blank, as though even that small discipline were no longer worth the effort. It was only later, at the hospital, that I sorted through the worn black leather wallet I'd given him one Christmas and found the appointment card.

The laws protecting patient confidentiality are stricter than I'd realized. To my surprise, they apply even after the patient is dead. I was unable to extract any information from his doctor. What I know, I learned from a pamphlet I found in Art's briefcase.

Small-Cell Carcinoma and You: The ins and out of combined modality treatment.

On its front cover was a color photograph of a middle-aged couple, bathed in sunlight, walking hand in hand down a country lane. A stock image, but not, I think, randomly chosen. The photo had been taken in autumn. A few golden leaves shimmered on the trees, but most had already fallen to the ground.

I know from the receptionist that Art kept his appointment. Later he drove across town to Dunster, parked and waited. At three-thirty the yellow school bus discharged its passengers at the corner of Fenno Street. Art recognized several of the childrenâit wasn't the first time he'd watched them debark. But that day, Aidan didn't come.

At some point that afternoon he drove back to his apartment. He poured himself a glass of Scotch and sat down to his final task. As he wrote, the prayer ran through him like music playing inside him. He was not the one praying. He was simply a vesselâonce hollow, now filled with prayer.

Let not your heart be troubled.

If you abide in me, and my words abide in you, you shall ask what you will, and it shall be done unto you.

Abide in me, and I in you.

Abide in me.

M

y brother was buried on the first of Juneâcold for late spring, damp and blustery, the air redolent of sea. In twenty-five years of ministry he'd performed hundreds of funerals. He had preached eulogies and counseled widows, said blessings, held hands. But of all those he'd comforted, not one showed up on that blustery Saturday when Father Breen was committed to the earth.

The church was nearly empty that morningâSacred Heart, the church he had left in disgrace. The interim priest had declined to officiate, and so it was Clement Fleury who stood on the altar and pronounced the holy wordsânot the usual Mass of Christian Burial but the old Latin Mass, what Father Fleury called the Extraordinary Rite. Whether Art wished this explicitly, I can't say. Father Fleury may have done it to please my mother, or simply to please himself.

This funeral Mass, its licitness or illicitness, had for days been Ma's great preoccupation. Shocked, rent by grief, she became fixated on the words to be said over Arthur's body. By long tradition, a funeral Mass was refused in cases of suicide; but apparently the Church is not as obdurate as she once was. Rome now accepts the modern understanding of depression as an illness. In the space of a month my brother had lost his job and his home; he'd been diagnosed with a deadly form of cancer. In many people, even one of these blows might trigger a clinical depression.

This was how Clement Fleury explained it to Ma. Still she was not convinced. At her insistence, Art's obituary was unusually specific. She personally called the editor of the Irish sports page.

Died at home, of lung cancer.

She'd insisted that he read it back to her, to make sure this detail was not omitted. She wasn't taking any chances.

R

EQUIEM æTERNAM

dona eis, Domine; et lux perpetua luceat eis.

Father Fleury, old-school, still wore black vestments for funerals. His voice echoed in the empty space, his fine tenor climbing the steeple all the way to heaven. If any human voice could, Father Fleury's would reach the ear of God.

Our family clustered in the front pews: Ma and Clare Boyle on either side of me, behind us Mike and his boys. By unspoken agreement we'd left Dad at home in front of the television, to be soothed by his usual morning programs:

Wheel of Fortune, Judge Judy.

His hostility to the Church predated his affliction, and there was no sense in winding him up.

Across the aisle sat two full rows of Devines. Uncle Dick and Uncle Jackie had pooled their resources, as it were, and offered up their sons as pallbearers. Say what you will about Ma's family, they are unfailingly loyal. Whatever they felt about Art's public disgrace, his alleged transgressions, they would not disown him at the end.

A small cluster of parishioners sat in the rear pews, at a respectful distance from the family. I recognized Attorney Burke, his wife and their daughter Caitlin, her eyes rimmed with red; Fran Conlon in her lavender coat. (She apologized for it later: it wasn't right for a funeral, but she didn't own a black one.) We stood in numb silence as the four young Devines brought in the box, which Ma had chosen from a catalog at Galvin Brothers Funeral Home. It wasâif such a thing can be said to existâa lovely coffin: gray with a nacreous sheen, like the inside of a seashell. The Devine boys placed it on its stand, head pointing toward the altar, a special distinction reserved for priests.

Out the corner of my eye I saw Clare Boyle crane her neck. “Where's Leo?” she whispered.

I stared at her in disbelief. Apparently even the Oracle has her blind spots: after all these years she'd failed to grasp the basic architecture of our family.

Of course

Norma and Leo would not be seen at Art's funeral;

of course

Brian and Richie McGann had refused to bear his coffin. In death, as in life, Art was no McGann.

Requiem æternam dona eis, Domine; et lux perpetua luceat eis.

I inched closer to my mother. For the first time in thirty years, I slid my hand into her coat pocket.

Her fingers intertwined with mine. Our hands were exactly the same size. It was like holding my own hand.

A

FTER THE

Mass we processed to the cemetery. I rode in the hearse with Ma and Art. In one hand she held the ticket stub I'd found in her pocket.

We rode shoulder to shoulder, hands still entwined. She did not meet my eyes as she told her story, the last evening she had spent with Art.

His invitation had come out of the blue, a gift fallen from heaven: Symphony Hall, the Boston Pops. Art had bought the tickets without telling her, a late Mother's Day gift. Anticipating her objections, he'd arranged for Clare Boyle to sit with my father. Ma would be free for the entire evening, her first night out in years.

As she spoke, I pictured her in dark lipstick, the green dress she'd bought, years ago, for Mike's wedding. On Arthur's arm she entered Symphony Hall, to his eye and mine the most beautiful building in Boston. He'd heard dozens of concerts there, and yet the place never failed to affect him. Each time he walked down the aisle to his seat, he was filled with a kind of awe he'd felt only in churches. That night Ma felt it, too.

“Fancy,” she whispered as they took their seats.

On the program that night was a premiere of a new violin concerto Art was keen to hear. Ma had no interest in classical music, but when the soloists stood she couldn't believe her eyes.

“They were ladies,” she told me, still sounding amazed.

The show ended, Ma and Arthur walked out into the spring evening, the air balmy and redolent of blossoms. Arm in arm they walked a few blocks, to a little bistro Art knew. He'd reserved the table under Ma's name, but he needn't have worried. Without his collar he wasn't recognized. In all the years he'd come to Symphony Hall, he had never encountered another priest.

For Ma it was the height of luxury: dinner downtown with her favorite son, at ten o'clock yet. For forty years she'd lived by Ted McGann's timetableâhis shifts at the factory, the evening festivities from which she'd long been excluded, the nightly circuit of bars up and down the South Shore. Now Dad no longer goes out at night. He no longer notices time one way or the other, and yet Ma adheres to the old schedule: dinner cooked, served and eaten, the dishes washed and the kitchen sanitized, in time for the local news at six.

At the restaurant Arthur ordered musselsâMa's favorite, though I have never known her to cook them at home. (Dad's interest in fish begins and ends with the Friday fry-up; I have never seen him touch shellfish of any kind.) With dinner she drank a pint of Guinness, another rare pleasure. She hadn't had a pint in donkey's years, had avoided the stuff entirely after Ted got bad. For years you couldn't have a sip in his presence; it wasn't worth the grief. I witnessed these arguments many times as a child: if Ma drank one, Dad considered it permission to finish the case.

The evening, for Ma, was magical. She will live on the memory forever, and I know that this was Art's intention. It was his way of saying goodbye.

T

HE RAIN

stopped just as we pulled in to the cemetery, but the sky couldn't be trusted. We assembled at the graveside beneath a dark green tent. It was an uncommonly sturdy model, chosen with Grantham burials in mind. The Galvin brothers manned it with the rough expertise of sailors, rushing to tie down a corner flap threatening to go airborne, leaving us mournersâa pitifully small group nowâunprotected from the rain.

In nomine Patris, et Filii, et Spiritus Sancti.

Father Fleury had changed out of his vestments, into clericals and a black balmacaan.

I glanced over Ma's shoulder, to see if any stragglers had joined us. To see for certain if the girl was gone. When the hearse parked at the foot of the hill, I'd glimpsed a young woman in blue jeans standing alone under the tent, gazing down into the empty hole. Art's headstoneâMa had chosen it a few days beforeâwas already in place: F

ATHER ARTHUR HAROLD BREEN, GOD'S SERVANT

. His grave set like a fancy banquet, waiting for the guest of honor to arrive.

The girl stood there a moment, smoking. Her hairâtousled, bottle-blondâwhipped in the wind. Then, spotting the hearse, she had hurried away, toward a lime-green Buick Regal parked at the crest of the hill. If Ma knew who she was, she gave no indication. She stared deliberately out the window, in the opposite direction, as if the girl were beneath her notice.

The girl's car started loudly, its radio blasting. I saw her arm flick a cigarette out the window. Then the Buickâscarcely smaller than our hearseârolled slowly down the hill.

Now, conceding to the weather, Father Fleury sang an abbreviated blessing.

Recto tono

, plain chant: each syllable on the same note, a graceful lilt at the end of the phrase.

There was a long silence.

“Arthur's family invites all of you to join them at their home for coffee and refreshments,” he said softly. He sounded a bit abashed, like a Pavarotti obliged to interrupt his performance to point out the fire exits and toilets.

Another clap of thunder urged the mourners toward their cars, until only Ma and I stood at the grave site. I stared at Art's lovely container, delicate as a jewel box. It seemed a shame to put it in the ground. I imagined my brother inside it, dressed in his white alb, chasuble and stole. To my great relief we'd been spared what locals called

the viewing.

This is standard practice within my tribe, the Irish Catholic diaspora of Greater Boston: interminable hours at Galvin Brothers, the corpse primped and displayed like a hunter's trophy, ready to receive visitors. Ma had decided against it, fearing that someone would make a scene: a reporter, an angry parishioner, embittered Catholic activists from Voice of the Faithful. Or, just as devastatingly, that no one would show up at all.

I watched her approach the coffin and lay her hand gently upon it. Her eyes were tightly closed, as though she feared what she might see.

“Take your time,” I whispered. “I'll meet you in the car.”

The Galvin brothers stood by at a respectful distance, hands clasped at groin level, the Adam pose. They are gentle bachelors, kind and self-effacing, alike as twins. The older Galvin had been a schoolmate of Leo McGann's, though if he noticed Leo's absence, or my father's, he gave no indication.

“About ready, then?”

“My mother needs a few more minutes.”

“Of course. No rush, dear.”

The

dear

was unconscious, nearly automatic; yet for some reason it made my throat ache. At that moment I couldn't bear even that small kindness. I turned away, blinking back tears.

Another gust of wind. The hearse waited at the bottom of the hill and I hurried toward it, holding down my skirt. It was the same dress I'd worn four years ago to Gram's wake, so distinctly funereal that it seemed logical to leave it hanging in my old bedroom closet in Grantham, to be worn again when the next relative died. It is an unspeakable thought, the dark actuarial calculation performed by those of us with aging parents, as one by one they falter and fail. Guiltily we wonder who will be next. For many years Dad had seemed the likeliest candidate. In those days, a late-night phone call could set my heart racingâthe Massachusetts Staties surely, having pulled his remains from flaming wreckage, unwrapped his truck from around a tree. Dad is safe now, but Clare Boyle is ripe for a heart attack, and Leo's lungs won't last forever. As that whole generation shuffles toward the grave, who would have imagined that Art would be the next to go?

As I neared the hearse, I saw a woman struggling down the path, a stout white-haired person in a lavender coat.

“Fran,” I called.

She turned. “Oh, Sheila. God help us.” Her eyes were swollen, her face streaked with tears.

“Watch your step.” I caught up with her and gave her my arm to lean on. “It's slippery from the rain.”

We walked in silence for a few moments. I felt raindrops like pinpricks through the back of my dress.

“I'm surprised to see you here,” I said finally.

“I had to come. Father was good to me. To the whole parish. He was a good priest.” She lowered her voice. “No matter what anybody says.”

Anybody.

I wondered if she'd seen Kath earlier, hurrying away from the gravesite. My heart was racing. I had to ask.

“You don't believe it?”

“I don't know what to believe.” Fran stopped a moment to catch her breath. I saw that her chin was trembling. “She's my own daughter. But Father was my friend.”