Faith and Betrayal (13 page)

A fresh wave of fanaticism permeated Zion in 1856. Disaffection and widespread apostasy—brought on by a combination of unrelenting poverty, unhappiness with the daily reality of polygamy, and whisperings of blood-atonement murders— threatened the stability of the church and Young’s despotic sway. That year a swarm of locusts—what would become known as the “Mormon cricket”—decimated the fields of Deseret, leading to a famine of devastating proportions. Collective morale plummeted, and Saints began to abandon their barren farms, setting their sights on newly settled California.

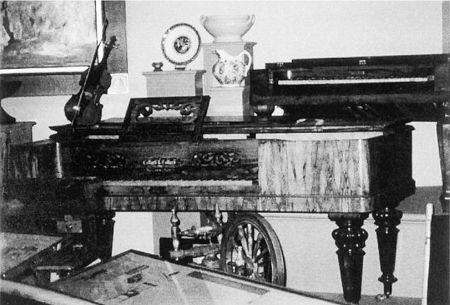

Jean Rio’s piano was dismantled and crated, its crate dipped in tar to

weatherproof it for ocean and river crossings. The inlaid Collard &

Collard square grand was the first piano brought by wagon train into

the intermountain West—a rare treasure. The Mormon prophet

Brigham Young acquired her beloved instrument after the

once-wealthy Jean Rio had been reduced to poverty. It is now on

display in the Museum of Church History in Salt Lake City.

A move to California became synonymous with apostasy to those who remained loyal to Young, and those who fled did so in darkness and secrecy and with justified fear of swift and cruel retribution.

Meanwhile, Young’s plan to transport thousands of poor Scandinavian converts across the plains was producing tragic results. In the early years of emigration, the church’s Perpetual Emigrating Fund had advanced money to European converts to make the journey to Salt Lake City—money that Jean Rio never had to use. The emigrants were obligated to repay the money at 10 percent interest once they arrived in Zion or in goods if they had no cash. But now Young announced that the church could no longer “afford to purchase wagons and teams as in times past.” He was, he said, “thrown back upon my old plan—to make handcarts, and let the emigration foot it.” That idea led to the greatest disaster in the history of western migration, exceeding by seven times the lives lost in the Donnerparty tragedy a decade earlier.

In what he said was a divinely inspired invention, Young conceived of a contraption, called a handcart, fashioned after those used by porters in New York City railroad stations. The lightweight handcarts were hastily constructed from unseasoned wood, measured the same width as a wagon, and had a handle like that of a wheelbarrow by which to be pulled or pushed. Five people were assigned to each cart, which was laden with their belongings; each emigrant was allowed to bring seventeen pounds of baggage that included clothing and bedding. For the sake of economy the wheels had no tires—a factor that would lead to many breakdowns. Insufficiently rationed, many emigrants starved as they endured frostbite during early snows on the plains. “With a morsel of bread or biscuit in their hands, nearing it to their mouths, could be seen men, hale-looking and apparently strong, stiff in death,” wrote a witness. The ill-conceived plan led to the deaths of sixty-seven in one blizzard alone. Many of those who died had been handicapped; they had been lured to Zion by missionaries promising safe passage and free land. Most Mormons at Salt Lake held Young personally responsible.

Fearing that his flock had become less zealous, Young ushered in the “Mormon Reformation”—a terrifying period church historians later referred to as the “Reign of Terror”— during which loyalist enforcers interrogated the settlers. Encouraging Saints to inform on their neighbors, family, and friends who were weak in the faith, Young’s “Avenging Angels,” or Danites—originally named the Sons of Dan by Joseph Smith for the man described in the Bible’s Book of Judges— were the enforcement arm of the prophet. A secret police that brought swift retribution to apostates and to antagonistic “Gentiles,” they were the elite unit of Young’s “Army of Israel.” “Backsliders were to be hewn down,” according to writer Josiah Gibbs. Young declared so in increasingly fiery sermons, verbally attacking the apathy or outright defection that undermined the urgent task of building his “Biblical City of Zion.” During the winter of 1856‒1857 church elders swept through the Mormons’ homes, demanding that everyone be rebaptized and forcing church members to answer fourteen questions:

Have you shed innocent blood or assented thereto?

Have you committed adultery?

Have you betrayed your brother?

Have you borne false witness against your neighbor?

Do you get drunk?

Have you stolen?

Have you lied?

Have you contracted debts without prospect of paying?

Have you labored faithfully for your wage?

Have you coveted that which belongs to another?

Have you taken the name of the Lord in vain?

Do you preside in your family as a servant of God?

Have you paid your tithing in all things?

Do you wash your bodies once a week?

If Saints admitted to laxity, or if their neighbors testified against them, they were required to renew their commitment to the faith, endure various forms of penance, and vow allegiance to the prophet. Untold numbers tried to leave the territory, mostly in vain, as the religious extremists gained dominance.

During the “Reformation,” Young preached inflammatory sermons about adultery and apostasy, transgressions so grave, in his eyes, that they could be cleansed only by slitting the throats of the sinners from ear to ear. “There are sins that can be atoned for by an offering upon an altar as in ancient days,” he thundered in one such speech. “And there are sins that the blood of a lamb, or a calf, or of turtle doves, cannot remit, but they must be atoned for by the blood of the man.” Openly embracing the doctrine that had been concealed since the earliest days of the church, Young sent panic into his followers and outrage into the nation at large.

In March 1857 the prophet began to escalate his rhetoric against the U.S. government. Railing against America, he issued a defiant proclamation in July 1857 that his government in Utah, and only his government, would decide which laws would be enforced in the territory. President James Buchanan considered Young’s posturing treasonous, and he made armed intervention in Utah a priority for his new administration. That spring and summer Buchanan appointed three new federal judges, a U.S. marshal, and a superintendent of Indian affairs to be installed in the territory. They would be accompanied by more than twenty-five hundred troops under the command of Brigadier General William Harney. In announcing his action to Congress, Buchanan claimed it was his duty to restore the supremacy of the Constitution and laws.

A young Brigham Young in the

summer of 1857

,

a few months

before the Mountain Meadows

Massacre and in the midst of his

defiance of federal authority in the

so-called Utah War.

While awaiting the “invasion” by the U.S. Army, Young exhorted his followers, already intimidated by the “Reformation, ” to prepare to avenge the blood of the prophet Joseph Smith or to face violence themselves. Then, on September 7, 1857, the Mormon militia attacked a wagon train of “Gentiles” passing through Utah laden with gold. During a brutal fiveday siege, the Mormons shot approximately 140 people, slitting the throats of the dead so that their blood would be returned to the earth in accordance with the doctrine of “blood atonement.” The victims, mostly women and children, were slaughtered despite a pledge of safe passage.

Like many of her fellow Saints, Jean Rio was horrified upon learning the whispered details of the Mountain Meadows Massacre—an act of religious fanaticism unparalleled in American history. That Brigham Young bore significant responsibility for the crime—both before the event and in the ex post facto attempt falsely to lay responsibility on the Paiute Indians—undermined her faith not only in the religion itself, but also in the grandiose and corrupt leader. Her later descendants would point to the massacre as a decisive factor in her breach with the church. Though the church-owned

Deseret

News

did not report the atrocity, rumors whipped through the entire territory. Among the most terrifying reports were stories of the fate of apostate Mormons who had joined the wagon train, hoping to accompany it safely to California. The stories that were inevitably spread by and among those who had known them, the accounts of their brutal murder at the hands of their fellow Saints—zealots committing “blood atonement”—were shocking if not incomprehensible to the faithful. There were also numerous and moving stories of Mormon men who had refused to participate in the wholesale murder of civilians. The crime inspired widespread defections, though it was nearly impossible to leave the territory safely. That Jean Rio did not write of the event was typical of the moment; it was the most dangerous time imaginable for a disillusioned Saint to confide her thoughts, even to a private diary, and like thousands of like-minded Mormons she would carry the shame and secret throughout the rest of her life.

At least three of her sons—Walter, William, and Charles Edward—had been, by requirement, members of Young’s military force, the Nauvoo Legion, which drilled regularly at the tabernacle in Ogden. While there is no direct evidence that they participated in the atrocity, which occurred more than 250 miles south of Salt Lake City, the young Baker men would have had firsthand information from their fellow militiamen about the killings. “The whole United States rang with its horrors,” Mark Twain later wrote of the event.

As the U.S. Army marched toward Utah, Young imposed martial law and issued a proclamation: “We intend to desolate the Territory and conceal our families, stock, and all our effects in the fastnesses of the mountains, where they will be safe, while the men waylay our enemies, attack them from ambush, stampede their animals, take the supply trains, cut off detachments, and parties sent to canyons for wood, or on other service.” He ordered all non-Mormons to leave the territory, and he commanded all Saints to take three years’ supply of food and disappear into the wilderness rather than succumb to a federal military force camped near their city. Able-bodied men between the ages of eighteen and forty-five were organized into military units and the officers were ordered to be in readiness to march to any part of the territory on short notice. “I am your leader, Latter Day Saints,” he told them, “and you must follow me; and if you do not follow me you may expect that I shall go my way and you may take yours if you please.” Any Mormon who defied the proclamation would be put to death, he announced.

More than twenty thousand Mormons left Salt Lake City and the nearby communities, some one hundred men staying behind to torch the abandoned fields and homes as soon as the army entered the valley. Poor and now homeless, the ragged Saints obeyed, turning their backs on all they had struggled to build. In June 1858 Young, facing defeat and humiliation, reluctantly agreed to be replaced as territorial governor and to allow federal troops to occupy Salt Lake City. The soldiers marched in order through the city’s deserted streets. On July 4 Young called the refugees home. But many had exhausted their resources in the “Move South,” as it was called, and were forced—or chose—to remain in the temporary settlements and begin anew.

Jean Rio was fortunate in that she was able to return to the crude dugout she had constructed in Ogden, but her future held little promise. “The famine of the year ’57 and the move south in ’58 are matters of history,” she wrote later. “I need not say that I passed them both, and a bitter experience it was.” No longer enamored with or even trusting the church, she now began to regret deeply the fateful choice she had made nearly a decade earlier, feeling she had been lured to a sinister “kingdom” under false pretenses by prevaricating missionaries. Still, as she lost her faith in Young as a divinely inspired prophet, and in the Church of Latter-day Saints as pure Christianity restored on earth, she fell back on her innate spirituality and strengthened her belief in God. Young had turned out to be the very bogus, betraying intermediary between God and the individual that Joseph Smith had warned against, and Jean Rio, like many of her fellow Mormons of the time, began to see the current church as an irremediable corruption of Smith’s inspired institution.