Farewell (13 page)

Authors: Sergei Kostin

The Vetrovs bought a quaint izba, a traditional Russian log house with a cowshed attached, for seventeen hundred rubles (less than four months of Vladimir’s salary). This purchase was a major milestone in their life. Vladimir, who had been brooding over his frustrations with the KGB, became a new man. Vetrov discovered his second nature of farmer–land owner, and he did not miss an opportunity to go to his “country estate.”

In fact, it was a five-year plan of hard work that awaited the Vetrovs. From 1977 through 1981, during the warm season, they spent almost all their vacations and weekends in Kresty. Vladimir was a fast driver, so they would get there in less than three hours. They left their car at the place of the previous owner of their house, who now lived by the Leningrad road. When they had heavy pieces of furniture and objects to transport, they exchanged two bottles of vodka or a case of beer for a horse-drawn cart. Besides tractors, those carts were the only means of transportation adapted to the dirt tracks filled with potholes. Otherwise, they walked the four kilometers, and when they arrived at their hamlet, they called Katia their neighbor, who took them to the other side of the river in her boat.

Contrary to most Muscovites who bought a house in the country as a starting point for long hikes in the woods, or to go fishing and hunting, the Vetrovs came to their place in the country mainly to work on the house. They wanted to make it their secondary home.

A carpenter they brought with them from Moscow dismantled the cowshed and built some kind of a bungalow. The Vetrovs removed the wallpaper, a symbol of comfort for villagers, in order to expose the magnificent logs. They partitioned the main room, brought in rustic pieces of furniture, a rocking chair, rugs, pelts, and candlesticks. Svetlana whitewashed the masonry of the Russian stove and decorated it. In the backyard, Vladimir and Vladik were building a terrace, and they hung an old cartwheel with chains as a decoration. The place gave the overall impression of belonging to an impoverished squire, just the way Svetlana had wanted it.

Among the objects discovered in the house was an icon, black with soot. Svetlana cleaned it and hung it in a corner of the room, but as an element of decoration only since, by definition, there could not be believers in the family of a KGB officer.

5

Another find would play a major role in Vladimir’s fate. As they were pulling off planks from the cowshed walls, Vladik and his father discovered a handmade tool forged by a village blacksmith. It was a pike about eight inches long, with a section shaped as a flattened diamond; it had two obtuse blades and a very sharp point. In the countryside, such tools were used to kill pigs. The pike was rusty and was missing its handle. Vetrov took it for repair to a KGB workshop. Once cleaned and fitted with a new handle, it looked like a paratrooper dagger. Vetrov kept it in the glove compartment of his car. One never knew what kind of encounters could occur on a deserted track in the Kalinin area (today the Tver region)!

Vetrov enjoyed himself thoroughly as a handyman in their country place. He was not that interested in mushroom and berry gathering. He would rather spend an entire weekend building an arch to connect the Russian stove to a beam, for instance. He was very proud of his work, and he never omitted telling visitors that he built the arch himself.

Having an impulsive temperament, he wasted a lot of energy for little efficiency. If he needed a plank, for example, he never made any measurements. He would grab his saw, and voilà, done! Too bad, the plank is too short. He would take another one and, still not using a measuring tape, cut it in two seconds. Now it is too long. He could go through three or four attempts before he would get it right. These details tell a lot about Vladimir’s personality.

The house was surrounded by a big yard, and the first autumn the Vetrovs had a bumper crop of apples. The winter of 1978–1979 was unusually cold, with temperatures down to minus fifty degrees Fahrenheit, and none of the apple trees survived the freeze. Svetlana compensated for the loss by planting strawberry patches and flowerbeds.

The Muscovites considered it essential to build good relations with the locals. The Vetrovs brought with them, for their neighbors, bags packed with salamis, cheese, canned food, and other food items impossible to find in the countryside. In return, they bought the assurance that nothing would happen to their place, no fire, no break-ins. The village residents who came to visit were greeted with a shot of vodka or a cup of tea with sweets. They were all so different from the people the Vetrovs socialized with in Moscow, and they had such strong personalities! Vladimir, however, kept his distance from the peasants, whose understanding of hygiene was not the same as his, and whom he regarded as boorish folks. Svetlana, for her part, spent most of her summers in the country, and she could not get enough of their storytelling, staying hours in their company.

In Kresty, there were only two permanent residents, two old women, two

babushki

(Russian equivalent of “grannies”). Katia, who owned the boat to cross the river, had a cow and goats. The Vetrovs bought milk, sour cream, cottage cheese, and vegetables grown in her garden. Maria Makarovna had worked as a maid for Lev Tolstoi Jr., the son of the great writer. She never ran out of stories to tell about her family and the lifestyles of Russian society at the beginning of the twentieth century. Since there was no television, listening to her stories was one of the main distractions available to summer visitors.

Lidyai, the gamekeeper, was another interesting personality in the area. He lived in the neighboring village of Telitsyno. With his large blue eyes and childish features, he was the gentle spirit of the region, displaying a rare kindness and innocence. The Vetrovs saw him often at the Rogatins’, whose house was separated from Lidyai’s by the river.

In fact, the Vetrovs and the Rogatins met mostly when they were in the country. Alexei, who was very good with his hands, transformed his property into an American-style ranch. He repaired two tractors, which he used as vehicles to go back and forth between his house and the Leningrad road. The Rogatins’ village was the closest to the road. Alexei and Galina Rogatin were the first Muscovites to establish a country home in the area, and both were very hospitable. For all these reasons, their house was a hub for all the Muscovites who had bought a house in the neighboring hamlets. On one stormy day, the Rogatins ran out of dry clothes; one after the other, three drenched families, among them the Vetrovs, had knocked at the door to warm up and change clothes before going on their way.

Every now and then, the Rogatins took friends for a walk to Kresty, the most picturesque village in the region. The Vetrovs, who enjoyed having company, always kept a bottle or two in stock, just in case.

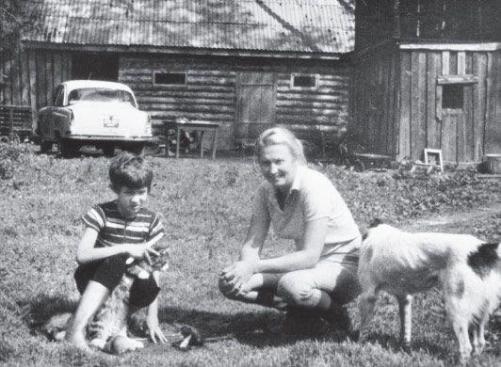

Svetlana and Vladik at their country house. Vetrov loved the place so much, he hesitated between defecting to the West or, once retired, driving a tractor for the local kolkhoz.

Whether in Moscow or on the banks of the Tvertsa River, the Vetrovs loved friendly gatherings around a festive table.

Knowing the Rogatins presented a major advantage for Vladimir. In Moscow, finding a good auto mechanic was a real nightmare. You had to get up at five in the morning if you wanted to be among the first ten lucky ones whose car would be taken in that day. Soviet grease monkeys were usually a rude and greedy lot, exacting a bribe of twice the official price the client had already paid. Furthermore, most of the time you then had to take the car somewhere else to fix their slipshod work. And as if it were not already enough, since the car owner was not allowed to stay to overlook the work, the service technicians could easily substitute a bad part for a good one. Finding a good mechanic, even for whatever amount of money he wanted, was a real challenge.

Alexei was an ace. All it took was for him to turn on the engine and drive your car a hundred meters to detect everything that was wrong with it. He worked fast, with no fuss, and at a very reasonable price. The Rogatins also presented the advantage of living in the heart of Moscow, on Smolensk Embankment. They lived in a huge Stalinist-style building that housed, on the first floor, the best art and antique gallery in town. The Vetrovs were regulars. Before long, Alexei took over the maintenance of the Vetrovs’ dark blue Lada 2106, bought when they came back from Canada.

From time to time, Vetrov would bring colleagues who had a car. Alexei already counted numerous KGB members in his patronage. First there was the UPDK, his employer, so deeply infiltrated by the KGB that it could be viewed as a subsidiary of counterintelligence. Then there was Valery Tokarev,

6

an old friend of the Rogatins. Although he did not know Vetrov personally, he was an officer at Directorate T, and he had been the last handler of the French mole Pierre Bourdiol. Tokarev, who was intimate with the Rogatins, introduced Alexei to a dozen of his comrades from the PGU, and all became steady clients. We are dwelling on this apparently trivial point because it will be quite significant later on.

In spite of their frequent get-togethers in the countryside and in Moscow, the two couples were not actually friends. The Rogatins found Vladimir contemptuous sometimes. Alexei even had an altercation with him one day. Vetrov let slip the word “yokels” in the conversation, talking about their country neighbors. Rogatin could not accept people who looked down on those who fed them and were in no way inferior to city dwellers.

This is also why Galina could not strike up a real friendship with Vetrov. She had the feeling that having lived in the West, where people were better off than in the Soviet Union, Vladimir could not adjust to the harsh realities of Russian life. In Vetrov’s opinion, this was a sub-life, and everything around was beneath him.

This is an important observation because it reveals what seems to be the double personality of Vetrov. There was in him this superior being—an aristocrat or a Westerner, although he was neither—who looked at the locals with contempt in a place where he was just a visitor himself. However, behind this superficial façade, there was also the son of a working-class family, the grandson of Russian peasants, who loved the countryside, its simplicity, and this special closeness between people so characteristic of Russian culture.

Depending on his surroundings and on the circumstances, Vetrov presented one side of his personality or the other.

Crisis

It may be said that Vetrov’s behavior became explicable as a midlife crisis. He was aware that what had not been accomplished was not likely to be accomplished later. Likewise, he knew his abilities but did not expect miracles. So, Vetrov realized that the future did not belong to him, and that he would never reach his goals and dreams. All this is apparent from what follows.

As early as during his school years, Vladimir considered himself to be clearly above average. He was the best student in mathematics in lower school, and then he did very well in one of the toughest higher education institutions. When he was hired by the KGB, he had to completely change his field of activity, but here again, he became one of the best operatives in his department. In addition to being naturally gifted, Vetrov had the perseverance and the will necessary to achieve a brilliant career. Yet, at forty-eight, he had been pushed to the side and was still a lieutenant colonel.

The Communist regime was in a visible state of slow decomposition. Intelligence officers, directly in contact with the reality of Western culture, had plenty of opportunities to compare the respective values of both systems. The comparison was not in favor of socialism.

In addition to the external erosion, the inside was rotting away

1

since, as already mentioned, the PGU officers recruited in the seventies were vastly inferior to the generation of the sixties.

Vetrov was not the only one to be appalled at the degradation of the service. One of his colleagues, in the office next to his, was a veteran, a former fighter pilot. He had been awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union, and he was only short of a second citation by three killings. He too was outraged by what he was observing around him and often would add fuel to the fire which was devouring Vetrov: “Is this what I went to war for?”

While this senior colleague was about to retire, Vetrov, who was still young, felt as a personal offense every promotion of a “connected” colleague, whether that promotion was a new post or a higher rank. He lost sleep over it. Svetlana would try to comfort him:

“What’s wrong with you that you need to torment yourself this way? That’s the way the system works—there is nothing you can do.”

“Do you think I am a failure?”

“Not at all. You simply are not the son of a minister. And you are unable—you refuse—to kowtow to your superiors. You want to be judged on your personal merit, but they couldn’t care less!”

“OK, maybe so…but my bosses are nevertheless incompetents, and I am head and shoulders above them!”

“So what? How many years do you have left before retirement? Four? You have your family, and Vladik is in college. We have our house in the country that you like so much. You’ll retire, and we’ll spend the warm season in the countryside. What more do you want?”

His male pride prevented Vetrov from taking the same view as she did. He had been working at the same post since they came back from Canada. The promise of nominating him as the head of the Analysis Department of the PGU Institute of Intelligence-Gathering Issues had not materialized yet. This institute had now been in existence since July 1979, following the PGU move to Yasenevo, and it had a new mission statement and a new organization chart. Vladimir’s boss, however, was in no hurry to let him go. Adding insult to injury, ten years had gone by since his posting in Paris, and he was still only a lieutenant colonel. Granted, a man with no connections and claiming no spectacular deeds could not become a general. As they say in the army, “Colonel is a rank, general is a stroke of luck!” An officer, however, owed it to himself to end his career with at least the rank of colonel. It was a minimum level below which a military man was considered a failure.

The situation bothered Vetrov so much that he was ready to do anything, even to lose his dignity. One day, he went to see his boss, Vladimir Alexandrovich Dementiev. This man had never been an operative; he was a Communist Party executive. He had been nominated to this position of responsibility within the PGU to meet the principle of “staff reinforcement” in practice at the time. It consisted of posting party executives, who were considered the “crème de la crème” in Soviet society, within departments that were considered as underperforming.

In the opinion of the officers who had stuck their necks out more than once, he got the job through his connections; he had no professional experience, and there was no tangible evidence that he ever contributed anything to the common cause. Needless to say that Vetrov and others thought themselves vastly superior to their boss.

Unfortunately, he was the man from whom Vetrov had to seek promotion. Arguing that he was nearing retirement, Vladimir asked to be promoted to the next grade, from the post of assistant to the post of chief assistant. Actually, the highest rank associated with this new position was lieutenant colonel. However, there was still a slight chance that he could be promoted to colonel, for instance, through a short mission abroad or the publication of an important analytical paper.

Dementiev’s reaction was violent and typical of a Communist Party executive: “You have a lot of nerve, Vetrov! You do not ask for a promotion. You work hard, dutifully, and with dedication. Then your superiors notice and can act accordingly. But you’re pushing it! What a lack of humility!”

Life is tough…an assistant at the end of his career aspires to be promoted to chief assistant, but his application is rejected. Why make such a big deal out of it? This Gogolian incident, trivial at first glance, was nevertheless registered in Vetrov’s investigation file used to try to establish the motivations of his betrayal.

2

Besides Vitaly Karavashkin, another man studied Vetrov’s file in depth. His name is Igor Prelin. Although long retired, this colonel is in excellent physical shape and sparkling with energy. An “intellectual’s” gray goatee on a lean military face, quick reflexes, a memory like an elephant’s, competent, he is the author of several books and documentary films. For a long while, Prelin was part of PGU internal counterintelligence. A French-speaking agent, he had several extended stays abroad, although never in France. The analysis of Vetrov’s betrayal, one of the major cataclysms that shook the KGB edifice, was one of his professional tasks. In interviews with Sergei Kostin, Prelin never attempted to fool him, hide facts from him, or brainwash him. Naturally, he would declare here and there, “I cannot tell you his name,” or “We do not care about the date here, do we?” Overall, he was a reliable witness, and, therefore, we often refer to his declarations.

Although rebuffed by his boss, Prelin states, Vetrov did not give up. He tried a new approach to reverse the situation. Around 1981, he wrote an analytical report proposing a radical overhaul of scientific and technological intelligence. In order to have the means to complete his project, Vetrov asked for permission to study the information produced by thirty-eight foreign agents recruited by the PGU in various countries. Such information, naturally, was top secret and Vetrov first wrote it down in his notebook, which he kept in the safe at the office. The analysis of the data resulted in a twenty-page document explaining what was wrong with the service, and suggesting a whole series of measures to remedy the situation. Vetrov analyzed every step of the process; information research, gathering, processing, exploitation, distribution, and protection. The changes to be made to improve the system’s operation were far-reaching, targeting residencies abroad as well as Yasenevo personnel, and even the beneficiaries of intelligence data within the military-industrial complex.

This task took Vetrov at least a month to complete. He did not hesitate to take his highly sensitive manuscript home. Svetlana, who remembers it too, read the document to proof it. Then Vetrov had the document typed and, with pride, submitted it to the department chief.

As he told his wife, for once his work would not go unnoticed. By that time, however, nobody at the PGU was willing to make any extra effort. The machine was running smoothly, with a regular exchange between residencies and the Center (for those who were allowed to go abroad), people were quietly climbing the career ladder, getting promotions…so why bother?

Whether Vetrov’s conclusions lacked merit, or the task was considered the responsibility of a superior, Vladimir’s report was filed away, coming to nothing. This humiliation occurred soon after the latest severe blow to his pride, and it played a decisive role in the turn his life would take.

Family troubles added to his professional setbacks and frustrations. The Vetrovs had been married over twenty years. According to their friends and acquaintances, love affairs were part of the couple’s life. Not just Vladimir. Svetlana too had been unfaithful for years, and regularly. Some would even add that she was the one who started it. That may be true. It is worth noting that, when talking about the Vetrovs, most witnesses had a tendency to blame the wife and excuse the husband.

At the end of the seventies, Svetlana, they say, had an affair with a Boris S., the brother of a well-known astronaut. He was good-looking, self-confident, and had a lot of charm. He had a prestigious and enviable job as one of the pilots attached to Brezhnev’s fleet of helicopters.

The lovers were not trying to hide that much; Vladimir knew the man very well, since he had been a friend of theirs for years. They had been in athletics together. The trio would often be seen together. Boris would come visit the Vetrovs at home. More than once, Boris took Svetlana to Kresty in his Volga, and they would spend a couple of days there. The Rogatins even teased Vetrov about the situation: “You don’t mind them going there by themselves, without you? You don’t have electricity in your dacha.” Vetrov would answer by another joke. Deep down, however, he could not ignore the true nature of Svetlana and Boris’s relationship. Evidently, this was a blow to his self-esteem. Besides, he was unable to hide his feelings. As part of his personality, he needed to unburden to others. Several of his PGU colleagues who knew about his private life confirmed that he had a hard time coping with Svetlana’s adultery.

Boris was madly in love with Svetlana. He had a successful career still ahead of him. Vladimir had been sidelined, and the only future he could hope for was retirement. The couple was getting close to their silver wedding anniversary, and in his wife’s eyes, Vladimir did not have the appeal of novelty anymore. Svetlana knew him by heart. All things considered, it may be precisely for that reason that she did not want to leave Vetrov.

Svetlana claims today that Vladimir adored her. He was always very attentive, catering to her every whim, and he was affectionate and cuddly. Before leaving for work, he wanted a kiss. The minute he arrived in his office, he would call her on the phone. He did not have anything special to talk about, he was simply missing her already: “What are you doing? Where are you going this afternoon? What are the plans for tonight?”

Back home, he would protest if his wife was slow to greet him.

“Where is my kiss, little fox?”

This was the term of endearment he used for her.

“Here is your kiss. Your dinner is waiting for you in the kitchen.”

“No, come eat with me!”

“I am not hungry.”

“So just stay with me.”

According to Svetlana, things were that way during the twenty years of their marriage.

Furthermore, Vladimir had gotten into the habit of relying on Svetlana for everything. He would do the shopping with her shopping list. There was a large food store at the street level of their building.

“They had beautiful ham today,” he would say, coming back home.

“So you got some, I hope,” Svetlana would answer.

“No, I didn’t.”

“But why?”

“Because you did not tell me to!”

Svetlana would scold him jokingly, and he liked it. This state of affairs suited him just fine.

As she recalls this late period of their married life, in the fall of 1980, Svetlana admits that Vladimir was undoubtedly deprived of affection. In those days, she remembers, she was spending all her time taking care of puppies born from their shih tzu dogs. It is more likely that she was unavailable because another man was on her mind. She says that this period lasted almost six months, enough time for the puppies to grow up and find a home.

After those six months, Svetlana suddenly realized that her husband had changed. He was not calling her from the office anymore; he was not asking for hugs. She suspected that there was another woman. At first, she thought of fighting back, but her pride was stronger. That another woman could have had preference over her was in itself offensive enough. She would not further humiliate herself to win back a man who had betrayed her.

As she was answering questions asked by Sergei Kostin, this journalist who had come to investigate her husband’s life, Svetlana avoided mentioning that Vetrov’s adulterous behavior might have been in reaction to hers. In fact, during her conversations with Kostin, they never talked about Boris or her own love affairs. Outraged as she was at her husband’s apparently serious liaison, she probably had forgotten all about hers.

In any case, the relationship between the Vetrovs got gradually worse. Their lifestyle changed, too. Their house used to be open to all and full of life. Vladimir could show up, with no advance notice, in the company of four or five buddies to eat at home. The guests were, for the most part, Vladimir’s PGU colleagues and a few “clean” friends who had worked with him at Minradioprom. Svetlana would then rush out to go shop in order to feed the party.

Now, he was coming back home alone, often late, and more and more often, drunk. One evening, Vetrov was

delivered

by a colleague who could barely stand on her own feet. She looked like a madwoman with her fur hat slipping over one ear. And yet, she had done a good deed; Vladimir was so drunk he could not utter a sound. Without his colleague, he would have been picked up by the police and sent to the drunk tank to sober up. Svetlana and Vladik let the woman pet a puppy, and then they put her in a cab.