Farewell (24 page)

Authors: Sergei Kostin

The closer the ultimatum date, the edgier Vetrov became. On their routine walk from the parking garage to their home, Vladik raised the issue again: “Dad, it’s time to cut this Gordian knot.”

“What do you mean?”

“Well, I know the way you are; you’re going to try to sweet-talk her again. Dad, you’ve got to be tough! Only fear will silence her. I am coming with you, by the way!”

Vladimir agreed reluctantly. He clearly needed support, so the two men devised a plan.

February 23 was Soviet Army Day. It was not a public holiday, but military personnel, KGB members, and policemen celebrated without fail, at the office and at home. The day before, February 22, even if most employees left the office at the regular time or fifteen minutes earlier, few were truly working during the afternoon. “I’m going to rest at work,” as the Soviets used to say. Parties were organized here and there in offices, and every man considered a past, current, or future defender of the homeland received a small gift. This was, in fact, some kind of “Men’s Day,” soon to be followed by “Women’s Day” on March 8. A good opportunity to have a frank discussion with Ludmila.

For Vladik, February 22 was the first day of the second semester. It was also his turn with his classmates of the same year to take part in the construction of a new MITKhT building in the southwest of the capital. During the day they had to work at the construction site, and in the evening they had to be in class in the old building located at 1 Malaya Pirogovskaya Street.

Classes were over at eight thirty p.m. On February 21, Vetrov promised his son he’d come pick him up the next day after class. Then they would go together talk to Ludmila.

“We’ll have to be tough, Dad,” repeated Vladik.

“Yes, fine, we will.”

Vladik went to bed reassured.

His dad, however, had his own plan.

February 22

What happened that day is still so vivid in the minds of the surviving witnesses that years later it is possible, at times, to reconstruct the sequence of events to within five minutes. Here are the main moments.

1

It was still pitch dark when the phone rang. Svetlana turned on the light of the bedside lamp. The alarm clock showed 3:25 a.m. The phone rang again. Svetlana answered.

“Hello!” said a female voice she knew too well by now. “May I…talk to…Vladimir Ippolitovich?”

Svetlana put the receiver on her pillow and got up.

“It’s for you,” she said on her way to the bathroom.

She did not want to be there during their conversation. When she came back, Vladimir had hung up already. He was lying on his back with his eyes open. A bolster separated the bed into two independent territories, that’s how bad things were.

Svetlana looked hard at him.

“Now, that’s really going too far!” she said in her contained, slightly nasal voice. “She’s calling you in the middle of the night now! I have to get up early to go to work, and your son, too. Can’t you at least change this part of it?”

Vladimir did not answer. Svetlana looked at him, got back to bed, and turned the light off.

She often remembered that scene. Would things have turned out differently if she had not said anything? And yet, she had not raised her voice nor made a violent scene.

She could sense that Vladimir had trouble going back to sleep. Was he thinking about the day ahead, slowly, methodically, hour by hour, action by action? After all, he was a professional. He had to be used to preparing his secret meetings with his KGB agents and, recently, with his French handler. Did he, at any moment, have the feeling that on this Monday February 22, 1982, his life was about to be turned upside down? For a year now he had had the feeling of sliding down a bobsled track head-on at top speed. Despite the risks the slightest mistake would have exposed him to, he told himself that he had a good chance to finish his journey. Even though irrational, some people persist in believing they are protected.

Vladimir lay awake after the phone call and got up when the alarm clock went off. As he went to the bathroom, then to the kitchen to drink his morning coffee, he ran into Svetlana several times. Each time, she moved away as if avoiding a tree, not looking at him, which made the situation visibly easier on him.

He got dressed with great care. His wife had taught him to take care of his appearance. Svetlana remembers exactly the way Vladimir was dressed that day: an elegant Italian shirt, a French tie, a navy blue three-piece suit with fine stripes, and a warm reddish-brown sheepskin coat.

He was about to leave, when his son came out of his room.

“Oh, you’re leaving already?”

Vladimir gave him a friendly tap on the back.

“So, Dad, we do as planned, right?” asked Vladik again, knowing how moody his father could be.

“Yes. Tonight, eight thirty, in front of your department building.”

The PGU headquarters were south of the capital, in the woods of Yasenevo. On days when he did not have his car, Vetrov would get on the bus at the terminal located not far from his home, in front of the memorial stele on Kutuzov Avenue. But on that day in February, Vladimir drove his Lada to work. Because the PGU provided transportation services to its thousands of employees, at 6:00 p.m. dozens of buses loaded officers and regular employees who were going back home in various parts of town. Car owners had to wait a good fifteen minutes to let the buses leave first. This detail gives a fairly precise idea of the time at which Vetrov left “The Woods” with Ludmila to drive her back home. If they left before the buses, it must have been around 5:50 p.m.; if they left after the buses, it was around 6:15 or 6:20 p.m.

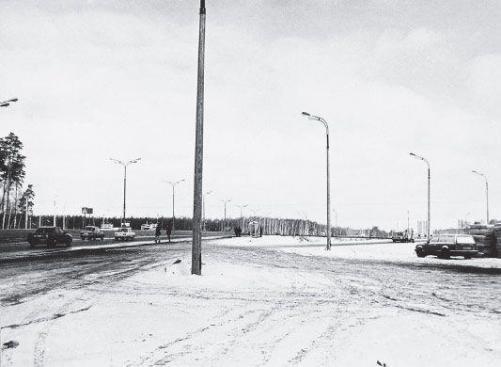

They drove clockwise on the Moscow Ring road since Yasenevo was in the southeast and Ludmila lived in the northwest of Moscow. On the way, soon after the intersection with Rublevo Road, the highway widens, forming a parking area, always vacant at night. Vetrov and his mistress would sometimes park there to stay together a little longer.

The place was deserted. On the right, woods surrounded weekend homes. Nobody waited at the bus stop, about a hundred meters further away. On the left, cars were driving by at a sustained pace. Like a strobe, headlights lit the inside of the Lada. In February it is dark at 6:00 p.m.

The parking area along the Moscow Ring road where Vetrov’s descent into hell began.

What exactly did happen in the pitch darkness of this remote suburb? The lights of a car streamed into the Lada where two lovers were drinking champagne in paper cups. The next car passing disclosed a man who, with his eyes wide open, was blindly stabbing a woman.

Vetrov kept two weapons in his car: a genuine hunting knife with a very sharp blade, used to cut branches when the Lada was stuck on a dirt road full of potholes; and the pique for slaying pigs he had found in their house in Kresty, which was the most frightening weapon. He chose the pique.

Ludmila struggled desperately as the pique was thrust into her again and again. As Vetrov braced to stab Ludmila one more time, he heard a knock on the car window. He turned around. A man was looking into the car. Apparently, he had just realized that the couple inside was not making love.

“Get lost!” Vladimir shouted through the window.

But the man was not scared away. He shouted, “What are you doing!” as he grabbed the door handle.

Vetrov shouldered the door open, violently. The man, fifty-something, was thrown back.

At that moment Ludmila found herself outside the car; Vetrov stabbed the man in the abdomen. Bleeding, Ludmila ran toward the bus stop in the hope there would be people waiting there. Suddenly, headlights beamed behind her; the Lada was chasing her.

Toward the end of the day, Svetlana felt very unwell. As if it were a thick black cloud, an overwhelming anxiety invaded her, making her heart heavy. She left the museum a little earlier than usual and walked home to get some fresh air.

The doorbell rang at 7:15 p.m. Svetlana opened the door. A rare occurrence at the time, Vladimir was sober. His eyes were opaque as if made of glass, though. When he came in, Svetlana noticed that he had blood on the back of his neck. That day, roads were terribly icy. She thought Vladimir had fallen or, worse, had been in a car accident or caused one.

“Are you wounded?” she asked.

“No, I just killed somebody,” he cried.

“Here we are, delirium tremens!”

Although they were not talking to one another, Svetlana, being a good wife, helped Vetrov take off his sheepskin coat. The collar was soaked with blood; even his suit and shirt were stained.

“You must have had a serious accident!” said Svetlana on her way to the bathroom to wash the blood off the coat.

“I killed somebody, I told you,” answered Vladimir. Emotionless, he said, “Those are spatters. I’ll change and go get Vladik.”

Curiously, now that her bad premonition of the afternoon had been fulfilled, Svetlana felt much better. It took her only a moment to absorb that her husband had committed a murder. Without articulating it to herself, she was compelled to experience two different but complementary states. On one hand, there was the serene and absolute certitude that everything that had, up to that point, made her life quiet and happy was over. From that moment on, nothing would ever be the same, and the future would hold only trials and misfortunes for her. On the other hand, she had the feeling all this happened to someone else. She could not be this woman washing off the blood of a human being killed by her husband.

Through the noise of running water, she heard the door slam shut. Vladimir had left. It was about seven thirty p.m.

Vetrov had an hour left before meeting his son. He drove around the Triumphal Arch and headed in the direction of the open-book-shaped COMECON building. He then turned into Smolensk Embankment and entered into the yard of the building where the antique shop was.

The Rogatins were home. Galina was wearing a robe, and they were about to spend a quiet evening watching TV.

Vetrov had an unusually neglected appearance. He was wearing an old parka, and his hair was tousled. He seemed, most of all, very agitated.

“Look at you, you’re a mess! What’s up?” asked Galina.

“Give me a drink. I just hit a woman with my car. It sent her flying. I believe she’s dead.”

“Damn!” said Alexei. “Where is your car?”

“In your yard.”

Since it was time to take their young boxer for his evening walk, anyway, Alexei took his dog and left.

Galina took Vetrov to the small kitchen. She poured both of them a generous glass of peppered vodka. Thirty minutes later the bottle was empty. Galina noticed that the vodka had no effect on her or on Vetrov. She kept repeating, “Is he crazy, or is it me?”

Vetrov now told her that he had given Ludmila a lift home. On the way, they had stopped by the loop. Vladimir added that a bus had just stopped there and people were getting off. This detail makes the rest of his account more implausible. Vetrov pointed out that his intention was to settle their conflict in a friendly manner. But Ludmila said something that made him angry, and he was beside himself. He grabbed, he said, a hammer to hit her. A hammer blow knocked her eye out, he said. These details—the hammer and the wounded eye—are pure fantasy but are of great significance.

Vetrov described accurately how he killed the man who had intervened, even mentioning that he used the pig slaying pique found in his country house. Then, he said, he intended to finish Ludmila off, but in the meantime she had managed to get out of the car and was trying to run to the bus stop. So he threw the weapon away, got back behind the wheel, and drove behind Ludmila, giving her a direct hit with the car. The shock threw Ludmila several meters away, where she landed, lifeless.

At this moment of Vetrov’s account, Alexei came back home.

“What are you talking about? I looked at your car, and there’s no trace of anything.”

Vetrov’s Lada was indeed like new. No sign of impact anywhere, neither in the front, the fenders, or the hood. This model—the Six—had plastic trims around the headlights. At the slightest shock, those trims broke or were dislodged. But both were still in place and intact.

“I’m telling you so!” screamed Vetrov.

Alexei did not insist.

“What do you want from me?” asked Galina.

Calmly Vetrov pleaded, “Could we pretend I was here with you?”

Having experienced prison, Galina sighed.

“Volodia, you’re already in jail. Even if your Ludmila had been killed by a street hooligan, you would be the first to be taken in for questioning. Do you have money to leave to Svetlana?”

Agitated now, Vetrov answered, “Yes, yes, I’m supposed to get some from Leningrad.” Then, looking down at his watch, he said, “Damn! I’ve got to go; I am supposed to pick up Vladik at university. I may be back.”

Not wanting trouble, Alexei exploded.

“Be back? What for? If you committed a murder, go to the police! Why are you dragging us into your mess?”

As soon as Vetrov left, Alexei went to the phone. It was to call Svetlana.

Vetrov was about five minutes late. Vladik walked toward the meeting spot. He was standing in front of the archive building, on Bolshaya Pirogovskaya Street. At the other end of the street, a few hundred meters from where Vladik was, a car suddenly sped toward him. Before he could even recognize their Lada, Vladik knew it was his father, and he knew that “it had already happened,” as he said.

He was therefore not surprised by the smell of blood in the car when he got in. His father was very tense, and Vladik understood this was no time to ask questions.

“You killed her?” he simply asked.

Vetrov nodded.

“And on top of it, I did a guy in.”

He drove off like a madman. The smell of blood inside the car was so strong that Vladik felt nauseated. He pressed his hand on the seat and realized the seat cover was moist. He moved a little to look and realized it was covered with dark stains.

“Wait,” he said to his father. “We need to remove the seat covers.”

Vetrov applied the brakes. They had just turned into Plyushchikha Street. A little further, in front of a building entrance, there were two large dumpsters. Vladik removed the covers, including the back seat cover which was also spattered, and stuffed them into one of the dumpsters and got back in the car. The smell was still there, pungent. Vladik discovered blood on the floor mats, and he removed them too.

“Dad, we’ve got to wash the car,” he said. “The wheels, the inside, the whole thing.”

Vetrov nodded in agreement.

The drive between Plyushchikha Street and their house took five minutes. Too short for Vladik to ask his dad to tell him everything that had happened. He just learned that the murder took place near a spot where they used to go swim in the summer.

2

When they arrived home, only Svetlana’s mother was in the apartment.