Farm Boy (3 page)

‘One year later, give or take a week or two, and I come along. There was a swallow’s nest under the offices – the eaves – right above the window of my bedroom where Mother would sit with me that first summer of my life. Always loved swallows I have, since the day I was born. Always will, too.’

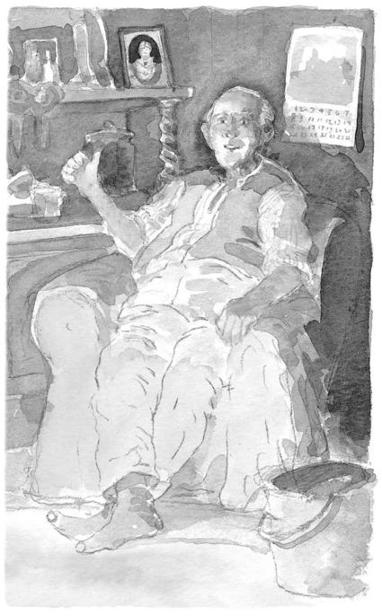

Grandpa loves to tell his stories, and when he does, I love to listen. But it isn’t just the stories I like – to be honest, I’ve heard most of them several times before – it’s the way he tells them. He talks with his eyebrows, with his hands. And he’s good at listening, and that makes me want to talk. He listens with his eyebrows, too. We just get on. We always have. I don’t know why really. After all, we were born into two completely different worlds. He’s an old country mouse through and through, and I’m a young town mouse – bus at the end of the road, supermarket round the corner, leisure centre, that sort of thing. I don’t much like

The Bill

or

Columbo

or Agatha Christie films; but when I’m staying with Grandpa I watch them because I like watching him watching them, his eyebrows twitchy with excitement, his hands gripping the arms of the chair.

But then there are times when he can be a right old goat. On days like that I just keep out of his way, and he keeps out of mine. He’d get to be suddenly sad and silent and never looking at me, and I’d know then. When he didn’t polish his boots last thing at night – that was a bad sign. He wouldn’t ever have the television on when he was like that. He’d just sit and stare into the fire. He could barely drag himself out of his chair to shut up the chickens at night. He was angry or sad about something, but I didn’t know what, and I knew better than to ask.

And then last summer, when I’d just finished school for the last time, exams all over and done with, and I was down on the farm for a while, he told me what it was.

Until now, Grandpa had hardly ever said a word about my grandmother. He had a photo of her on the dresser in the kitchen, and I knew she’d died before I was born, that he’d been alone for some years. I knew nothing more about her, and I didn’t like to ask. He was in one of his deep grumps, sitting by the stove in his holey socks, when I came in for my tea. I’d been cleaning down the cowyard. I didn’t expect him to speak.

‘I was thinking about her on the dresser,’ he said. It took me a moment or two to work out who he meant. ‘Be twenty years today. She went and left me twenty years ago today. Everything to me, she was, and she goes and dies on me. And you know what? We was in the middle of something, something we hadn’t finished. And she took ill and died. She shouldn’t have. She shouldn’t have.’

‘What were you in the middle of?’ I asked.

He looked at me and tried to smile. ‘You’re a good lad. Come to think of it, you’re something like her, y’know. You let a fellow be when he wants it. There’s others that have guessed it, your Mum and Dad for sure; but her on the dresser, she’s the only one I ever told. I told her before I married her, and she said it didn’t matter, that there was more important things about people than that. Nothing to be ashamed of, she said. Bless her heart. She was shamed right enough, she must’ve been. Course, once I had her with me, I didn’t need to do anything about it, did I? I mean, she did it all for me. And I had all the excuses I needed, didn’t I? There was the farm. I was out working morning, noon and night; and there was the children growing up and mouths to feed and rent to pay. Oh yes, I had all the excuses; but truth of it was that I just didn’t bother.

‘Then with the children growed and flown the nest, more or less, she said we both had the time to do it. She said we should sit down together in the evenings when I come in off the farm, and do it. And so we did. No more’n a month later, I wake up one morning and she’s still in bed beside me. She was always up before me, always. And she were cold, so cold. I can mind I knowed at once she was dead. Weak heart, the doctor told me. She had the rheumatic fever when she was little. I didn’t know it. She never told me.’

He waved me into the chair opposite him, and looked me long and hard in the eye before he began again. ‘I still talk to her, y’know. Last night I asked her. I said: “Shall I tell him? Would he do it? What d’you think?” And she was listening, I know that. She never says anything, but it’s like I can hear her listening, hear her thinking sometimes. Like last night. She was thinking: “It’s about time you finished what we started. No use just sitting there for the rest of your life feeling all sorry for yourself. Ask him, you old misery. Worst he can say is no.” ’

He reached out suddenly and took me by the arm. ‘Well, will you?’ I still hadn’t a clue what he was asking me. ‘Will you stay here for a few months? You could give us a hand out on the farm. I’d pay you mind, proper man’s wages. And maybe…’ He was looking down at his hands, picking at his knuckles. He didn’t seem to want to go on. ‘And maybe, you could teach me, like she did. I’d learn quick.’

‘Teach you what, Grandpa?’ I said.

‘I can’t read,’ he mumbled. ‘And I can’t write neither.’ There were tears in his eyes when he looked at me. ‘You got to teach me, lad. You got to.’

‘But you went to school,’ I said. ‘You told me.’

‘Till I was thirteen, and I wasn’t bad either. Few wiggings for this and that, but we all had wiggings, ’cepting Myrtle. Oh, she could read and write something terrific. Didn’t help her much though, did it? She went into service up at Ash House and died of the diphtheria before I was twenty. Poor maid. Pretty as a picture she was, too.

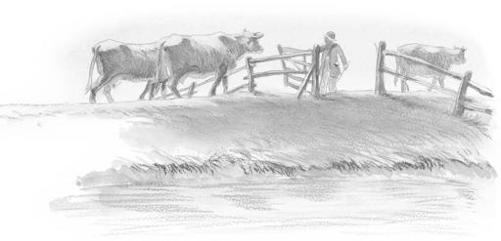

‘I never had the diphtheria, but I got the scarlet fever. I’d have been all right without the scarlet fever. Missed a year of school with that. And then when I got better, I wanted to be out on the farm all I could. I’d fetch in the cows before I went off to school. I’d feed Joey in his stable, and old Zoey too. It was near enough a two-mile walk to school after that. I was late most mornings, so I got a wigging of course; but I never took no notice of that. Trouble was, I was always dropping off to sleep in Mr Burton’s lessons, and he didn’t like that; so then I got a wigging again. And sometimes, if the brown trout were rising down on the Ockment, I’d bunk off school anyway.

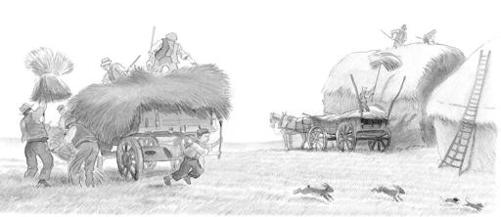

‘Harvest times, of course, I never bothered much with school anyway. I’d be out in the fields, sunrise to sunset if need be. Hay in June, wheat in July, potatoes in October, cider apples too. I’d go rat catching at threshing time, bash ’em on the head as they came a-skittering out. I’d trap the beggars too, when I could. Father’d give me a penny a tail for that. And he’d give me sixpence for a nice rabbit.

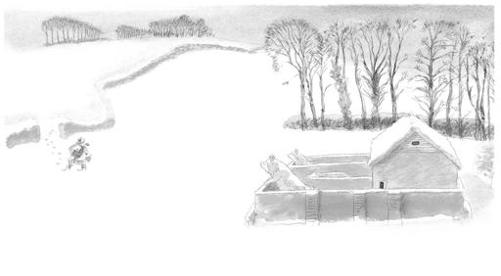

‘Father couldn’t do it all on his own, see. He weren’t ever well enough. Leg from the war played him up something rotten, and he still had the ringing in his head, and the pain with it. Mother helped when she could, but they couldn’t have managed without me, ’specially at harvest time.

Always something to be picked up, there was: mangolds, swedes – I do love a good swede – turnips too. And stones. I used to be out there with Mother days on end, picking up the stones off the corn fields. Weren’t slave labour. Father paid me for every bushel I picked up, and I’d give half of everything to Mother for the housekeeping. But I was happy enough to do it. You ask me where I’d rather be, in Mr Burton’s writing lesson at school, or cleaning out the pigs? Pigs any day. Honest.