Fatal North (10 page)

Authors: Bruce Henderson

“I would like to reach a higher latitude than Parry before I get back,” Hall said.

More than forty years earlier British explorer Sir Edward Parry had set out by sledge for the North Pole. Before turning back, he reached latitude 82 degrees, 45 minutes northâa proximity to the Pole not attained since by white explorers.

“I would like to have you along, butâ” Hall abruptly stopped. He pointed at the sailing master strutting on deck like a rooster. “I find he is a man I cannot place any trust in,” he continued, a tinge of sadness in his voice. “I have been close to putting him off duty for his conductâstealing food and drinking. I have decided to give him one last chance. If he does not conduct himself well in my absence, I will suspend him upon my return.”

Tyson said nothing; he could see how the matter pained the commander. Tyson had suspected Buddington of drinking on several occasions since leaving Greenland. He had seen him wobbling on deck with unsteady stepsâHall certainly had, tooâand knew that no good would come of it.

“I don't know how to leave him with the ship in my absence,” Hall went on. “If something happens and the vessel should break out of the ice, it would be better for you to be aboard to assist with the ship.”

Hall explained that if the ice broke up and the ship was forced from her position, steam should be gotten up as quickly as possible and no time lost in getting the vessel back to her former position, where the sledge party would return to.

“I understand, sir,” Tyson said.

Hall presented another scenario:

Polaris

might end up stuck in the ice on a southward driftâas had happened to other Arctic expeditionsâand be unable to return for the sledge party. In that case, Hall said evenly, he and the other men ashore would fend for themselves, and the

Polaris

crew should care for themselves and the ship.

Tyson knew that Buddington wasn't the only

Polaris

officer Hall didn't trust. The commander had confided in him that he didn't think Dr. Emil Bessels was qualified or equipped for the position he had been assigned. Tyson knew, as did everyone else on board, that the commander and the ship's doctor did not get along, and for the most part only barely tolerated one another in the course of their official duties. The rest of the time they were like two alpha wolves eyeing the other.

“I would like to go on the sledge trip, of course,” said Tyson, intending not to reveal just how much he wanted to go. “I am willing to remain and take what care of the ship I can.”

“Thank you, my friend,” Hall said humbly. “I want you to know again that you were right. Had I listened to you we would right now be much farther north than we are.”

The next day, Buddington surprised Tyson by asking him what he and Hall had discussed.

“I couldn't tell you,” Tyson answered evasively.

“I'm in a helluva scrape, but something will turn up to get me out of this,” Buddington said. “You'll see if it don't.”

“What's going to turn up?” Tyson asked stiffly.

“Well, you'll see,” Buddington said, slurring slightly. “I have been in a good many hard scrapes, and always something turned up to get me out.”

Buddington had been drinking again.

“Considering where we are stuck for the indefinite future,” Tyson said, “you might find this one harder to get out of.”

“Oh, I'll get out of it. That old son of a bitch won't live long.”

Following a week's worth of preparations, in which Hall had everything they were going to take weighed so as to not overburden them, they seemed ready at last. They had outfitted with provisions and other supplies a single sledgeâfitted with wagon wheels in the event they came to areas without enough snowâto be pulled by twelve dogs.

On the evening of October 10, Tyson and some of the men helped haul the heavy-laden sledge up the steep hill at the top of

the promontory. They stood by as the sledge drove off across the plains, north by east, dogs baying woefully and the Eskimo driver cracking a whip overhead.

After the other men had returned to the ship, Tyson watched the sledge party become smaller against the white, frozen backdrop. He watched for as long as he could, then turned and went slowly back to the ship stuck in the ice pack.

6

“How Do You Spell Murder?”

E

ven after all the preparation and packing, Tyson had no doubt that his commander had forgotten something. Charles Francis Hall was, he knew, rather peculiar that way.

The day after the sledge party departed, Hans returned alone on foot with a missive from Hall. He was to bring a second sledge and more dogs so that they could divide up their heavy load. They had also forgotten not one item but several, and Hall and the rest of the party, consisting of first mate Chester Hubbard and Joe, were waiting five miles off for Hans to return with them.

Among other things, they needed more candles, dog lines, and coffee. Also, Hall wrote, “Do not forget my bear-skin mittens, which I left behind by mistake. While Hans is absent, we are to go on a hunt for musk-oxen. Hasten Hans back without the loss of a moment. May God be with you all.”

The sun set behind the mountains on October 17 and would not be seen again that winter from the ship. For the next few days the only way to observe the slimmest patch of sun was to venture to the crest of a high hill. Then even those rays soon sank from view.

As the sun departed, the perpetual twilight deepened.

The crew began banking up snow around the ship to keep the frigid winds from slicing through the berthing compartments. They started by cutting blocks of snow from an icy bank and sledding them over to the vessel. When they were finished some weeks later, a wall up to eight feet thick and as high as the top of the ship's bulwarks would be in place, with a flight of snow steps leading up to the port-side deck. Blocks of freshwater ice from rain and snowfall were also cut from the nearby berg and transported to the icehouse aboard ship; from there, it would be melted on a stove, as needed, for drinking water. Other men worked on fixing up a canvas awning to cover the main deck. When it was completed, an opening was made in the awning at the top of the snow steps just over the forward gangway.

Stores of all types had been moved ashoreâcoal, clothing, guns, ammunition, and a portion of everything that would be most needed. They were packed in a ramshackle shed built mostly by Tyson. It could have been made stronger with more lumber, but Buddington refused Tyson's request for additional wood from onboard ship.

In Hall's absence, Buddington's behavior grew worse. Dr. Emil Bessels had a supply of high-proof alcohol, brought aboard for medicinal and specimen-preserving purposes, that was mysteriously declining. Bessels decided to set a trap and confront the culprit. One morning when everyone else was outside busy at chores, the doctor hid in the pantry near the locker where the alcohol was kept. In short order, he heard footsteps and the locker door swinging open. He sprang out of the pantry.

Before him stood Sidney Buddington, uncorked bottle in hand, ready for a morning eye-opener. Bessels grabbed for the bottle, but Buddington refused to let go.

“You are a drunk and a thief!“ Bessels screamed. “You are unfit!”

Buddington grabbed the smaller man by his shirt. Pinning the doctor against the bulkhead with one arm, Buddington

tipped the bottle to his lips with the other. “I will have a drink whenever I want.” He smacked his lips. “And

you

mind your own business!”

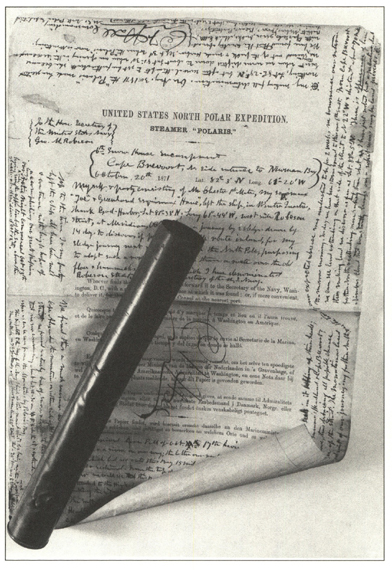

The last message written by Captain Hall, while on his final sledge journey. It was addressed to Secretary of the Navy Robeson on October 20, 1871, four days before Hall took ill.

(Smithsonian Institution)

Bessels managed to free himself and darted off.

Hall's sledge party returned on October 24. They had been gone two weeks.

Tyson, who was helping bank snow around the ship, shook hands with Hall.

“How are you, Captain?” Tyson asked.

“Never better,” an exuberant Hall replied.

The commander seemed invigorated rather than exhausted from his travels. Although they had hoped to go a hundred miles, Hall said they had made only fifty due to the configuration of the land. Nonetheless, he was encouraged.

“I think I can go to the Pole on this shore,” an excited Hall told Tyson.

Hall went around to every man working on the ice and warmly shook his hand like a long-lost relative. He and his party then went aboard ship, and Tyson and the other men went back to shoveling snow.

Â

Inside the fifteen-by-eight-foot upper cabin that Hall shared with five others since giving up his stateroom to serve as a winter galley, William Morton helped the commander remove his wet boots and outer fur clothing.

Hall said he was not hungry, but he took a cup of coffee brought to him by the steward, John Herron, a small, quiet Englishman.

Morton took away Hall's wet clothing and went to get a shift of fresh clothing from the commander's private storeroom. When he returned not more than twenty minutes later, the second mate found Hall looking pale and vomiting. Morton now noticed Dr. Emil Bessels in the cabin.

“What's the matter?” Morton asked.

“A foul stomach,” replied Hall.

Morton helped Hall into fresh clothes and began washing his feet.

Hall had sent for Hannah, who now entered the cabin. She had earlier gone onto the ice to welcome back her husband and the commander, whom she lovingly referred to as “Father Hall.” She had found both pleased with their journey. Hall told her he would “finish next spring,” which Hannah construed to mean that he felt confident of reaching the Pole.

“I've been sick,” Hall told her.

“What is it, Father?” she asked worriedly. “Did you get cold?”

“It's my stomach. I'll be better in the morning. Hannah, make things ready for my next journey. I will leave in two days. I will take Tyson and Chester, Joe and Hans.”

Hannah and Morton helped Hall into his bunk.

An hour later, Tyson entered the cabin. Word had reached him on the ice that Hall had taken ill.

“What's wrong, Captain?” Tyson asked.

“Sick to my stomach. I think I'm bilious.”

“Would an emetic would do you good?” It seemed logical to Tyson that if something was upsetting his stomach, it should come up.

“An emetic may be called for,” Hall agreed. He had vomited already, he said, but felt the need to further empty his stomach.

“No, that will not do,” Bessels said, striding importantly to Hall's bedside. “It will weaken you.”

Hall, trying to get comfortable, winced and held his stomach in obvious pain. He weakly waved a hand at Tyson. “I believe we can take

Polaris

north to eighty-five degrees next summer. From there it will be a comparatively short distance to the Pole. Three hundred milesâwe can do it by sledge. I wish to go back to explore further right away, and I want to take you with me this time. We will be going north in two days.”

Tyson judged Hall's offer to join him a sincere one, and he felt gratified. But the commander did not look as if he would be going anywhere soon.

Before Tyson's eyes, Hall grew rapidly worse.

After complaining of the pain in his stomach and weakness in his legs, he dropped into unconsciousness. Bessels took Hall's pulse and announced it was irregularâfrom sixty to eighty beats per minute. The doctor described his patient's condition as “comatose.”

Tyson had never seen anything like it in all his years going to sea. One moment this healthy, vital man had been returning from an expedition, excited, invigorated, and the next he was sick to his stomach and weak and nowâ

comatose?

Bessels applied a mustard poultice to Hall's legs and chest.

In less than half an hour, Hall regained consciousness. In examining him, Bessels found that the commander's left arm and side were paralyzed. Hall complained of numbness on the left side of his face and tongue, too, and he had difficulty swallowing.

The doctor gave Hall a powerful cathartic; the laxative consisted of a dose of castor oil and three or four drops of croton oil.

Bessels motioned Morton and Tyson to follow him into the passageway. “I believe the captain has suffered an attack of apoplexy,” the doctor said. “The attack is serious. I don't believe the captain will recover.”

In his entry in the official journal of the expedition, Bessels would write in his neat, studious handwriting that he believed Hall had suffered “an apoplectical insult”âor stroke. He described the commander's paralysis as of both motion and sensation. He continued to prepare his fellow officers for the worst: the death of their commander.

About that the doctor would be correct: Charles Francis Hall was dying, although, not from an apoplectical insult or anything of the kind.

Â

Hall slept for several hours that night.