Favorite Greek Myths (Yesterday's Classics) (7 page)

Read Favorite Greek Myths (Yesterday's Classics) Online

Authors: Lilian Stoughton Hyde

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction

One day, as he sat on the ground by a spring, looking absently into the water and thinking of his lost sister, he saw a face like hers, looking up at him. It seemed as if his sister had become a water-nymph and were actually there in the spring, but she would not speak to him.

Of course the face Narcissus saw was really the reflection of his own face in the water, but he did not know that. In those days there were no clear mirrors like ours; and the idea of one's appearance that could be got from a polished brass shield, for instance, was a very dim one. So Narcissus leaned over the water and looked at the beautiful face so like his sister's, and wondered what it was and whether he should ever see his sister again.

After this, he came back to the spring day after day and looked at the face he saw there, and mourned for his sister until, at last, the gods felt sorry for him and changed him into a flower.

This flower was the first narcissus. All the flowers of this family, when they grow by the side of a pond or a stream, still bend their beautiful heads and look at the reflection of their own faces in the water.

H

YACINTHUS

was a beautiful Greek boy who was greatly loved by Apollo. Apollo often laid aside his golden lyre and his arrows, and came down from Mount Olympus to join Hyacinthus in his boyish occupations. The two were often busy all day long, following the hunting-dogs over the mountains or setting fish nets in the river or playing at various games.

Their favorite exercise was the throwing of the discus. The discus was a heavy metal plate about a foot across, which was thrown somewhat as the quoit is thrown. One day Apollo threw the discus first, and sent it whirling high up among the clouds, for the god had great strength. It came down in a fine, strong curve, and Hyacinthus ran to pick it up. Then, as it fell on the hard earth, the discus bounded up again and struck the boy a cruel blow on his white forehead.

Apollo turned as pale as Hyacinthus, but he could not undo what had been done. He could only hold his friend in his arms, and see his head droop like a lily on a broken stem, while the purple blood from his wound was staining the earth.

There was still one way by which Apollo could make Hyacinthus live, and this was to change him into a flower. So, quickly, before it was too late, he whispered over him certain words the gods knew, and Hyacinthus became a purple flower, a flower of the color of the blood that had flowed from his forehead. As the flower unfolded, it showed a strange mark on its petals, which looked like the Greek words meaning

woe! woe!

Apollo never forgot his boy friend; but sang about him to the accompaniment of his wonderful lyre till the name of Hyacinthus was known and loved all over Greece.

Perseus and the Medusa

A

CRISIUS,

the king of Argos, was once very much frightened by a saying of the oracle of Apollo, at Delphi. This oracle had said that King Acrisius would be killed by his own grandson. Now King Acrisius had only one child, a daughter, Danaë, and to prevent the saying of the oracle from coming true, he caused Danaë to be shut up in a strong, brass tower.

Nevertheless, when the spring came and the power of the sun grew greater, when trees began to put out their young leaves or their fuzzy yellow flowers, and when young lambs were bleating in the fields, the news reached King Acrisius that a golden child had been born in the tower.

The golden child was a beautiful baby with blue eyes, a clear white skin, and golden rings of soft hair, all of which the Greeks thought very wonderful.

King Acrisius was quite beside himself with fright when he heard this piece of news, and he immediately commanded that Danaë and her golden child should be put into a brass-bound chest and allowed to float out to sea.

So Danaë and her baby drifted slowly out to the great sea, where they had only gulls and a few smaller sea-birds for company. The waves rocked the chest gently, and the golden-haired baby slept in his mother's arms, and did not know that there was anything to fear; but Danaë thought of strong winds and high waves, and of sharks and other great fish that lived in those waters, and her heart was full of terror.

The chest drifted all night on a quiet sea. In the early morning, the tides brought it close to the island of Seriphus, where it became entangled in a fisherman's nets. Dictys, the fisherman to whom the nets belonged, when starting out for his day's fishing, saw the chest and drew it in. He took Danaë and her baby to his brother Polydectes, who was the king of that island. King Polydectes was willing that Danaë should stay on the island, and Danaë was very thankful for this kindness. She found a good home there; for Dictys and his wife took her into their own cottage, and did all they could to make her comfortable.

When the golden child, which Danaë named Perseus, grew up, he became a strong, handsome youth who attracted much attention from the people everywhere. King Polydectes began to wish that the brass-bound chest had never floated to the island of Seriphus. In fact, he took a great dislike to Perseus, a dislike which became an active hatred. The stronger and handsomer Perseus grew, and the more admiration his youthful strength and beauty called forth, the more King Polydectes hated him. He finally began to think over plans for getting rid of him forever.

PERSEUS

On a rocky, dreary, barren island which lay in the midst of the sea, a long way from the island of Seriphus and from every inhabited country, there lived three fierce sisters who were called the Gorgons. These strange sisters had faces like women, but do not seem to have been like women in any other respect. They had eagles' wings with glittering golden feathers, scales of brass and iron, claws of brass, and great fierce-looking tusks which must have made a strange appearance with their human faces. Worst of all, instead of hair, their heads were covered with venomous snakes, that were always twisting themselves about, and putting out their forked tongues, ready to bite anything that came within reach. The two oldest Gorgons had always been just such fierce creatures as they were now; but the youngest, who was called the Medusa, had once been a beautiful woman who was very proud of her long black curls. In spite of her beautiful face, this woman's heart was like the hearts of the Gorgons, and to punish her for a wicked deed she had done, the gods changed her curls into writhing vipers, and made her face so terrible that any one who looked at it was immediately changed into stone. In all other respects she became a sister to the Gorgons, and had to go and live with them. She was the most frightful one of all, because of her power of changing men into stone.

Now King Polydectes knew all about the Gorgons, and he made up his mind that there could be no better way of getting rid of Perseus than to send him after the Medusa's head. So one day he called the young man to him, and told him that he expected to be married soon to the Princess Hippodamia, and asked him to bring to the wedding feast, as his gift, the head of Medusa. He added, that unless Perseus brought the head with him, he must never come back to the island of Seriphus again; and then, to make matters worse, he shut Danaë up in an underground dungeon, and said she should not come out till Perseus brought him the head.

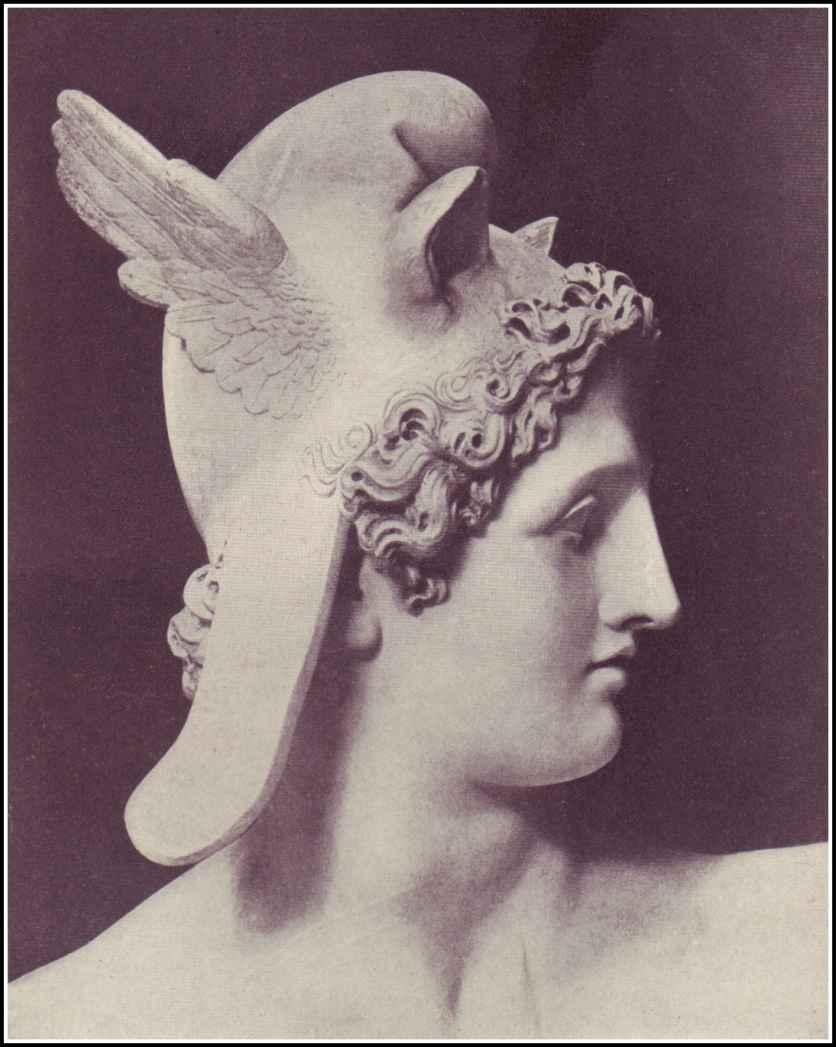

Perseus did not even know where the Island of the Gorgons was, nor how to find it. He thought it must be somewhere in the western sea, and as he stood on the shore, looking off at the place in the west where the sky came down to meet the water, he suddenly noticed that two people were standing on the sands by his side. One was a very tall woman who wore a helmet on her head and carried a very bright shield on her arm and a lance in her hand. The other was a young man with wings on his cap and on his sandals, a winged staff in his hand, and a crooked sword that shone like a flame, at his side. Perseus knew that the tall woman was Minerva and the young man Mercury, and that they had come to help him. This was just what he had been expecting, for the gods of Olympus often appeared at just the right time, ready to help those who were brave and determined to do all they could for themselves.

First Minerva told Perseus how to find the Island of the Gorgons. She said that he must ask the Three Gray Women, who were cousins of the Gorgons, and that nobody else in the whole world could give him the necessary information. Next she said that when he had found the Gorgons, he must not touch either of the older ones, because they were immortal, and he must by no means look at the Medusa, lest he be turned into stone. Then she took her own bright shield from her arm, and holding it high above her head, bade Perseus see how the shells and pebbles on the shore were all reflected in it. She said that when he was ready to strike off the Medusa's head, he must look at that terrible face only in this shield, which she would lend to him for that purpose.

Now it was Mercury's turn. He lent Perseus his own crooked sword, a sword so sharp that it would cut through brass or iron or any other hard substance. This was the only sword that would cut through the Gorgon's scales. Then he offered to show Perseus the way to the home of the Three Gray Women, who lived in Twilight Land,—a land lying somewhere among the mists that rose from the sea.

The two immediately set out. They journeyed far to the north till they came to a land of cold and fogs. The farther they went, the thicker the fogs became and the darker it grew. At last, in the dim light, they could faintly see, coming toward them, three very old women. Long gray hair hung over their shoulders; their garments and even their faces were gray; and they groped along in the fog as if they could not see. They seemed to be quarrelling about something. As they came nearer, the quarrel proved to be about the use of their one eye; for they were so very old that they had only one eye and one tooth among the three.

"Be quick, Perseus! Now is your time," said Mercury. "Seize their one eye, and then you can compel them to tell you how to find the Gorgons. They will never tell you of their own free will."

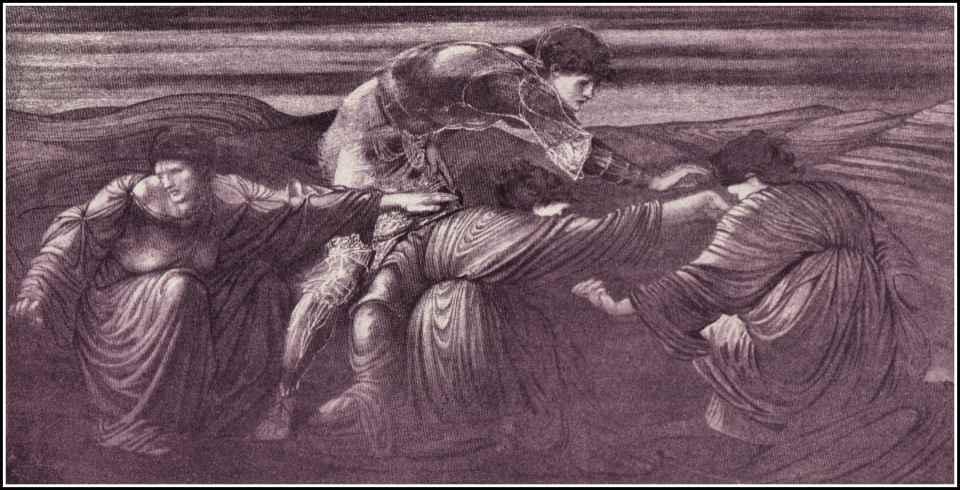

PERSEUS AND THE GRAIAE

So Perseus seized the eye, and would not give it back till the Gray Women had answered his questions. They said that the only way to find the Island of the Gorgons was to ask the Hesperides, the daughters of Night. These nymphs were the guardians of the famous golden apples in the Garden of the Hesperides, which lay near the place where the giant Atlas held up the sky.