Fearful Symmetry (31 page)

‘Yes. And she had an arrangement with one of the other staff. She could skip off to do her washing and the other person would have a break later on. She’d been to the workshop, calculated the size and done the calculation—how much gas had to be let in and for how long. It was obviously going to be easiest for her to come in at night and turn it on, which meant a relatively small amount escaping for between eight to ten hours. One of the gas taps turned on full would do it. I bet she went off to do the laundry around eleven that night and slipped out while the machine was on. She could have been there and back easily within fifteen minutes, especially if she already had Adele’s workshop key with her. She snuck in and turned the gas on full. It’s pitch black in the Circus, there are only about three street lamps, and the trees mean you can’t even see across it. She walked home as usual at the end of her shift and put the key back before anyone was up.’

‘We went about it quite the wrong way,’ Andrew said miserably. ‘Assuming it was an accident, done by Adele herself, and then working out that there had to be less gas escaping over a longer period. We thought we were dealing with an unlucky combination of circumstances. Look, the night after the bonfire. If you were awake all that time believing it was Herve, why didn’t you ring me then?’

‘What? Me? Ring you in the middle of the night? I wouldn’t

dream

of telephoning you at four o’clock in the morning, Chief Inspector. Would I?’

CHAPTER

39

U

H?

H

ELLO?

A

NDREW?

Happy New Year. God, I’m shattered.’ Sara, woken by the ringing telephone on New Year’s Day from deep, partied-out sleep, reckoned as she finished speaking that she could just about feel her lips.

‘Happy New Year of course, but I’m not ringing for that. In fact it’s nothing festive. Meet me out at Iford, would you? Quick as you can. Bad news.’ He may have said something else, but he was obviously speaking on a mobile phone and in the dips of the hills round Iford the sound was lost.

It was only a quarter to ten. James and Tom would not stir for a while yet, but when they did their expectation of a large late breakfast would be unfulfilled unless they made it themselves. Sara smiled at the thought of last night’s dinner, which they had cooked in her kitchen squabbling happily in the way of people dedicated in almost equal amounts to each other and, for the moment, their delightful foodie tasks. They had allowed her to set the table and she had prepared the dining room lavishly, since she used it less than half a dozen times a year, in the way she might bring out a Versace dress and take two hours getting ready to step into it. New candles the colour of buttermilk were set in the wall sconces. Along the sideboard she placed a dozen more, and instead of using candlesticks she stood them in Victorian glass dessert dishes which were far too gorgeously fragile for actual puddings. From the garden she cut holly and ivy and left it in long swirls down the centre of the bare polished oak table, curling round the stems of two plain pewter candelabra. She had busied herself with these little attentions for much of the evening, setting a single Christmas rose at each place, to avoid missing Andrew. Then the three of them had spun out the long minutes to midnight with a dinner of several delectable small courses eaten slowly between pauses for stories and gossip. They all drank enough wine to discuss the murders as if they had happened long ago.

‘You don’t think Poppy’s going to get off, do you?’ James asked. ‘She’s bloody dangerous.’

‘No, not “off” as such. But she’s pleading guilty and claiming diminished responsibility in both cases, Imogen Bevan and Adele, so she might get off with manslaughter. They’re still waiting for psychiatric reports. But she’s been a model of cooperation, according to Andrew.’

‘Ah, the power of love,’ Tom said facetiously. ‘Is Cosmo really standing by her, then?’

‘As long as she admits to everything. Cosmo’s conditions. You know he got a job at Duck Son and Pinker flogging amplifiers after Helene threw him out? I saw him in there, we had quite a long chat. He seems to like the shop and he’s got himself a room somewhere in Twerton,’ Sara said. ‘He said he was quite happy.’

‘How heartwarming. So Cosmo’s “found” himself as a result of his girlfriend destroying two other people, and herself. That makes it all right, then,’ James slurred. ‘There’s one good thing. At least he’s stopped trying to write music.’

‘I know. I couldn’t tell whether he felt some responsibility for what Poppy did or was just enjoying the moral superiority.’ She glanced at Tom. ‘But he hasn’t stopped composing. Oh, no. He’s writing an opera based on what happened. The whole story. We’re all in it.’

‘And James is being played by a girl, didn’t you say? A mezzo?’ Tom asked. ‘A trouser role?’

They sat back to watch James explode, which he did to their satisfaction. After a full ten minutes’ rant, he paused for breath.

‘

Jeez

, is there no limit? He’s fucking unbelievable! How can he—God! How . . .’ His voice faded again as he took in the look on Tom’s face. He glanced at Sara.

‘You . . .’

‘Just kidding,’ Sara said.

‘Don’t take on so, pet,’ Tom cooed.

‘Bastards,’ James muttered into his glass. ‘

Bastards

.’

Sara sighed. ‘But none of it’s funny,’ she said. ‘It all seems so wrapped up and finished with, but it’s not, is it? They’re still dead. And there’s Brendan Twigg. I wonder what’ll happen to him in the end.’

‘Who the hell’s Brendan Twigg? Is this another wind-up?’

‘Andrew’s first suspect. An awful character, according to Andrew, exactly what you’d expect him to be given what people did to him practically from the minute he was born.’ She sighed again. ‘All that fuss and effort to track down Brendan Twigg. Now Poppy’s in custody the police aren’t interested in him any more, of course. Nobody cares where he is. Nobody wants Brendan Twigg unless they think he’s done something wrong. That’s why I got Andrew to check with all the vets in York, unofficially.’

‘You

what

?’

‘Oh, it’s complicated. I just always hope there’s good in people somewhere, I suppose. Andrew was sceptical, he did it just to prove me wrong, and I wasn’t. A vet in York did treat a dog called Fonz in October. The owner answered Brendan’s description exactly. No address though. He spent over two hundred pounds on treatment, paid in cash.’

‘Sounds like a Britten opera.

Billy Budd, Albert Herring, Peter Grimes, Brendan Twigg

,’ James said.

‘Raise your glasses to Brendan Twigg!’ Tom said, picking up and waving the bottle.

As they did so Sara silently, sincerely wished him well.

A

NDREW WAS

standing halfway along the long path between the cloisters and the summerhouse, looking down, watching for her car. He stood as still as the garden itself; the light swirls of his breath vapourising in the frozen air were all that moved. She had parked by the wall of the manor. Seeing him up there, she waved. He may have nodded his head, but he did not wave back. As she climbed the frosty steps she glanced up from time to time to see if he would come towards her. He did not, not even when she reached the far end of the path he was standing on. She began to make her way along the frozen gravel, and only then did he turn and begin to walk slowly, unsmilingly, to meet her. Above the crunch of her own feet Sara heard voices, from a direction she could not determine. There were other people here. So they met without kissing. Andrew’s face was drawn, cold and pinched with waiting, but there must be some other, awful reason for the remoteness in his eyes.

‘This way.’

He strode ahead. She followed. As they entered the quadrangle of rose bushes, reduced to black barbed spikes, the knot of people assembled at the far end dispersed as discreetly as undertakers.

Orange tape hung between metal spikes in a rough half circle round a flattened patch of earth between rose bushes, on the edge of the long border.

‘This is where they found him. Phil. His body. This morning,’ Andrew said flatly.

‘Oh, no. No. How? Andrew, how?’ Sara pulled at his arm. ‘Andrew?’

‘Suicide. No doubt about it, there’s a note. A long note.’ Andrew stopped suddenly, raised his face towards the sky and took a deep breath. Sara could see that he was trying to stop tears gathering in his eyes. He turned back towards her. ‘Overdose. The really pathetic thing—no, just one of the pathetic things—is that in the note he gave the name of his student counsellor for us to contact when he was found. His

counsellor

—’ He broke off again, wiping at his eyes savagely with a gloved hand. ‘Not a friend. Not me. Not you, or any of us. His counsellor. Along with apologies for inconveniencing everyone.’

Stinging tears were running down Sara’s face. ‘What else? What else did it say?’

Andrew stared at the patch of earth as if he hadn’t heard. ‘Can you imagine the temperature out here last night? He hitchhiked out here. Got a lift with a man who lives just down there, next to the hall. Says he told him the garden was closed, but he wanted to come out this way anyway. Still, as he pointed out’—Andrew’s voice was bitter—‘not as if they celebrate like us, is it? Got a different calendar, haven’t they? Don’t even celebrate Christmas.’

Sara touched his arm. ‘Andrew . . .’

He jerked away from the contact. ‘So what if a bloke in his early twenties in a catatonic depression wants to be dumped on his own in the countryside at eleven o’clock on New Year’s Eve in minus six degrees? Free country, innit? Christ, I’m so ashamed.’ He turned from her, his face twisted in an expression of pain. ‘He didn’t come to any of us for help. And we didn’t take care of him. Any of us. We just didn’t notice.’

Sara reached again for his arm, this time firmly. She tugged him round and led him slowly along the path away from the insultingly jovial orange tape. They walked slowly and Sara, with an arm through his, held on tight. She tried to remember the latest she had heard, weeks ago now, when she had bumped into Helene and Jim in town. After he’d come out of hospital in mid-November, Phil’s sister had come over from Hong Kong and he’d gone back to university after three weeks. The opera had not been mentioned.

‘His counsellor’s a true bitch. Pointed out that her responsibilities towards students applied to term-time, not the holidays. Phil was being treated for depression and anxiety, following his discharge from hospital. She was seeing him regularly. His concentration was affected. His work was going downhill. He overdosed on his tranquillisers.’

‘Is that what his note says?’

Andrew shook his head. ‘No. His note doesn’t mention work. It’s all about Adele. Yet another thing we got wrong. His outburst at that rehearsal wasn’t about Adele being exploited over the music. He didn’t know anything about the music being sung backwards or forwards. Adele hadn’t told him that at all. The thing he’d realised was that someone there: Cosmo, or Jim, or Herve or even me, had been having sex with her. Phil and Adele weren’t exactly lovers, not in the straightforward technical sense, though it was fairly physical. The note says Phil wanted to wait till they were married. He really believed he would marry her. Anyway, something she did—it’s all in the note—made him see she was experienced, sexually. That was less than a week before she was killed. He’s been haunted by both, the death and the fact he thought she had been unfaithful, ever since. He couldn’t stop thinking about it. The poor boy didn’t consider that the concept of fidelity might have meant nothing, or just something else, to Adele.’

‘And it was all too much, in the end?’

‘Oh, his counsellor’s got it all explained, of course. Another student suicide: anxiety about work, fear of letting parents down, isolation, money worries. But in the end, none of that explains Phil.’ Andrew drew his arm from hers, took off his glove and found Sara’s hand. They walked on, their hands clasped in Andrew’s coat pocket.

‘Phil loved and lost,’ he said.

‘He lost, all right.’

Nor could it by any reckoning be better, Sara thought, that the tormented Phil had become a frozen, drug-filled corpse in the rose bushes, than that he never should have loved at all. They stopped on the path and looked down at the white meadow across the dark slice of the river. A crow on the head of the statue of Britannia watched the water. Black-fingered trees pointed into a sky full of snow. From here she could see across the brick tops of the wall and into the square vegetable garden. A few obedient lines of twiggy brassicas stood in the rimey squares of empty soil. Sara looked back across at the crow, its feet apparently frozen on to Britannia’s head, and back into the walled garden. She realised suddenly that she was standing now in the very spot where Phil had stood that evening, as she had hesitated on the bridge. She had been standing down on the bridge next to Britannia and had seen him stand just here, very still, in his pale yellow shirt. She looked back across into the vegetable garden and now she saw it: the space where Adele’s white bench had been, against the far wall, exactly halfway along. It had been taken in for the winter, of course, but she could see the interval in the espaliered fruit trees against the wall where it belonged. Phil had been standing just here on that warm September evening, watching Adele as she sat softly singing on the bench. He had been standing here, surely sensing, if not quite understanding the deep happy peace with which she had surrounded herself and which he must disturb if he tramped down and in through the garden door to be with her. His beautiful Adele. He must have felt something like contentment then, Sara thought, to be young on a golden evening, loving and watchful, keeping his beloved safe in her perfect garden before the world burst in and spoiled it all.

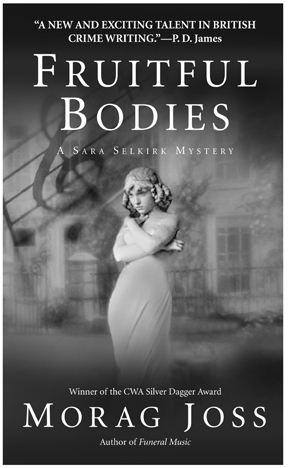

If you enjoyed Morag Joss’s FEARFUL SYMMETRY, you won’t want to miss any of her tantalizing mysteries set in Bath and featuring cellist Sara Selkirk. Look for the first Sara Selkirk mystery, FUNERAL MUSIC, at your favorite bookseller’s.

And read on for an exciting early look at the latest mystery by Morag Joss, FRUITFUL BODIES, coming August 2005 from Dell.

FRUITFUL

BODIES

by

MORAG

JOSS

FRUITFUL BODIES

On sale August 2005

S

OMETHING WRONG WITH

the lipstick. Joyce’s fingers, which were feeling twice their normal size, swivelled the base again and the thumb of puce lard twirled down out of sight and then welled back up out of the tube at her. She stared as it shimmered and wavered, eluding focus. Sniffing, as if this could somehow improve her eyesight, she gave it a push with one finger and inspected the smudge on her fingernail. That looked solid enough, so maybe it was only her lips that were wobbling. She wiped the finger down the front of her jacket and with another sniff looked firmly into the mirror that was held by a piece of wire to the handle of the cupboard above the Baby Belling. She sucked in a deep breath and tried to maintain a steady pout. But her reflection was telling her that the problem was not just getting her lips to hold still long enough to put the stuff on, it was the question of finding them first. They were developing a tendency to slip into her mouth and stay there, stuck to her dry teeth.

They had never been that great anyway. The gene pool of Monifieth in 1927 had not been overstocked with luscious Aphrodite mouths in the first place, and seventy-odd years of Scottish consonants, east winds and chewing politely had not fleshed Joyce’s out any. Across the crumpled page of her face her lips looked like two horizontal curly brackets of the sort that Joyce as a little girl had practised whole jottersful of at Monifieth Elementary School, along with sevens with wavy tops and treble clefs. Joyce allowed herself a moment’s recollection of the perfection of her treble clefs with an involuntary satisfied purse of her lips, before giving herself a shake. It was another tendency she recognised; if she grew for a moment inattentive, her mind would pull her back to a past so distant that even Joyce herself viewed it with scepticism. For how could they have been real, those treble clefs? She must concentrate on the here and now. She leaned in towards the mirror again, took another deep breath and stretched out her lips to receive a straighter gash of

Bengal Blush

.

Worse. Her mouth now looked like a newly stitched scar and time was getting on. She would have to allow extra for the underground walk, changing from the Northern to the Piccadilly Line at King’s Cross, especially in her best kitten-heeled courts which had been a good fit for the first eleven years but now slowed her down because she tended to walk out of the backs of them. That was the trouble with having Scottish feet, which were longer and narrower than Englishwomen’s, she had read somewhere. It sounded finer somehow, longer, narrower feet; yet another little superiority in which one could have taken a pride if more people had known about it, although it did make for a wee problem going any distance in the kitten-heeled courts.

She considered wiping all the lipstick off but

Bengal Blush

was the finishing touch, being the exact shade of her suit, the Pringle two-piece that she’d had for, well, did it matter how long, it was a classic. A classic re-interpreted for the modern woman, she remembered being told when she bought it in Jenners on Princes Street in Edinburgh, where it was called not a suit but a costume. Ladies’ Costumes, Second Floor. And the jaunty little poodle brooch for the lapel, she’d bought that in Hosiery & Accessories on the way out, unable to resist the picture she made of a professional woman with the style and means to travel from Glasgow to Edinburgh to buy her clothes, no Sauchiehall Street for her. And from Jenners! New stockings too, six pairs on a whim although by this time she was mainly showing off to the girl and the girl had known it, the tone of her ‘certainly madams’ carrying by then the merest acidity, the wee baggage. But she was getting off the point again. Concentrate on the here and now.

Joyce began to busy herself around the bedsit, collecting purse and keys and, from a suitcase under the bed, her good handbag and chiffon scarf. Only when she had gathered everything up in her arms did a sound from behind the one armchair, followed by the rattle of Pretzel’s claws on the linoleum under the sink, remind her that she had not left him any food and he had trodden in his water bowl again.

‘Och, Pretzel, was that Mummy going away and not leaving you your tea?’ she said.

She dumped her amassed accessories on the floor, mainly into the pool of spilled water, and opened a new tin of dog food while Pretzel’s rattling on the floor grew animated and the entire brown tube of dachshund torso wriggled in anticipation. The warm, already half-eaten smell that arose from the tin reminded Joyce’s innards that she was in need of sustenance too. As she stooped to put down Pretzel’s tea on the floor under the sink, where the smells of drain and warm dog were waiting to mingle with the scent of braised horse and gelatine from the bowl, her stomach, signalling its emptiness, pushed out a little shudder which puffed up through her guts and out of her mouth in a quiet, inflammable belch of vodka vapour. Sour saliva flooded the inside of her cheeks. Her throat puckered and she swallowed a mouthful of neat bile. No, not food. Something else. But there was only the remaining vodka in the bottle in her bag and she was supposed to be keeping that for when she felt the need, or for later on (whichever came sooner, if there was a difference) but what the hell, what was wrong with now? Here and now. She didn’t need to get there till the second half, anyway.

Some time later she closed the door and concentrated hard on the here and now of getting the key, which seemed to be trembling, into the keyhole, which wouldn’t keep still. From inside the room she could make out the burble of the television which she had switched on so that Pretzel would be less lonely, and thought she could hear Carol Smillie. Pretzel liked Carol Smillie. Joyce sighed with satisfaction as the key finally turned, and set off carefully down the stairs, her good handbag over her arm. Her slept-on, unbrushed hair, her bare, varicosed legs and the rickety

Bengal Blush

, all things which she had consigned to the there and then, concerned her not at all.

Sara was feeling sick in the usual way, that was to say, not quite unpleasantly so, and it was such a familiar feeling that it would have unsettled her to be without it. She had done her warm-up, showered, changed into the dark brown silk dress and fixed her face and hair, also in the usual way, which meant about an hour before she really had to. So she had walked about the dressing room, switched the radio on, cracked her knuckles, practised deep breathing, switched the radio off, made some faces in the mirror and asked herself why she did this for a living.

Outside, she could hear the hum of people who had leaked out of the Prommers Bar further along and were lining the stuffy bottom corridor around her dressing room door. They would be leaning on the walls fanning themselves with programmes, knocking back warm drinks and waiting for the second half, in complete if not comfortable relaxation. She would give anything,

anything

to be one of them, to be in a summer top and sandals at a concert, sipping heartburn-inducing house wine in the interval, the biggest challenge of the evening being the momentous decision on the way home between Chinese or Indian.

Feeling sorry for herself, she clipped on her diamanté earrings, the only jewellery she would wear with this slinky, chocolate satin dress, and turned her head to watch them catch the light of the dozen or so bulbs round the dressing room mirror. The earrings were too large for real life, and too showy even for some musicians she could think of, the professional mice who would consider the playing of the Dvo ák Cello Concerto at the Proms as a grave undertaking whose solemnity was not to be compromised by any flippancy in what they might call ‘the earring department’. Sara smiled to herself in the mirror. All the more reason to wear them, then. She liked the frivolous note they struck, and the question they raised—brassy or classy?—which led to the next question—who cares—as long as the Prommers enjoyed the bit of sparkle. What they made of her playing was up to them, once she had given them her best. The one-minute bell sounded and the hum in the corridor began to subside.

ák Cello Concerto at the Proms as a grave undertaking whose solemnity was not to be compromised by any flippancy in what they might call ‘the earring department’. Sara smiled to herself in the mirror. All the more reason to wear them, then. She liked the frivolous note they struck, and the question they raised—brassy or classy?—which led to the next question—who cares—as long as the Prommers enjoyed the bit of sparkle. What they made of her playing was up to them, once she had given them her best. The one-minute bell sounded and the hum in the corridor began to subside.

Now the shoes were on and she had, out of a mixture of superstition and supreme practicality, worked out the exact spot (a little above her knee) on the front of the dress where she needed to pick up the fold in her right hand and raise it before she took the first steps out on to the stage, if she were to avoid standing on her hem, ripping the dress, falling on hundreds of thousands of pounds’ worth of Peresson cello and impaling herself on her bow. The Prommers would love that.

The sick feeling was still there. She swigged some water from the glass on the dressing table, made her way over to the green velvet sofa and perching on the arm (she did not want to walk on stage with even one satin crease across her stomach) she rang Andrew on her mobile.

‘Hello. It’s me.’

‘Oh. Hello.’ Silence.

‘Look, I’m sorry.’ Sara sighed, less with regret than with the effort of apologising when she did not feel she had been at fault.

‘ ’S all right,’ Andrew said unenthusiastically. After another silence he added, ‘Me too. I’m sorry. But I have to put the kids first, don’t you see?’

Sara did, but she also saw that Valerie, Andrew’s ex-wife, should not have insisted that he look after them tonight at two hours’ notice. And she also saw that the result, her own barging angrily out of the house to drive up to London alone, was utterly understandable.

‘Andrew, I do wish you were here.’

‘Look—well, there it is. So, are you ready? Are you all right? I’ve got the radio on. First half was good. I do like those St Anthony Variations. But everybody’s waiting for you. How’re you feeling?’

‘Sick. Doing my deep breathing.’ She found herself smiling, as if he had just walked into the room. ‘It’s lovely to hear your voice,’ she added.

‘Oh darling, it’s lovely hearing you. I’m just so sorry I’m not there with you.’

‘Well, I suppose I’d have booted you out by now anyway, if you had been here. I need the time by myself, just before.’

‘Time to feel sick in, you poor beast. Look, you’ll knock ’em dead. Live from the Albert Hall. Enjoy it.’

Sara smiled at the unnecessary reassurance. ‘Oh I will, I will. I’m ready. I’m always like this before I go on.’

‘And look, drive back safely, won’t you? I’ll be here. The M4 should be fairly empty this late, but don’t do anything silly. I’ll see you later. Break a leg. I love you.’

‘I will. Love you too. Got to go. Bye.’

There was a knock on the door. ‘Three minutes, Miss Selkirk.’

‘Thanks,’ she called back. And she was grateful, not just for the call but because, as it always did, in that instant her sick feeling vanished. She stood up, stretched her arms up over her head, took two deep breaths and realised she was still smiling. Now the odd jumble of furniture, the pipes running under the ceiling and the fuggy warmth in the dressing room, that made her think she was in the bowels of a very old cross-Channel ferry, ceased to command any of her attention. With her cello in her left hand she crossed the now empty circular corridor that ran right round the building, and joined the leader and conductor in the passageway that led up and on to the stage. They exchanged kind nods and good wishes. The cue that told them that the orchestra had finished tuning came, and the leader made off up the ramp. Two stewards held open the double doors and nodded him through. The applause drifted back to Sara. Simon was looking at the ground. With a raising of the eyebrows and a gesture of the hand, he invited Sara to precede him. Now. She beamed at him and they exchanged a wink. Breathing deeply to control her excitement, she picked up the fold of her dress and stepped forward into the dark tunnel.