Fenway Park (39 page)

Authors: John Powers

Boston’s drought was longer by 22 years. But in the wake of an effortless 6-0 victory in the Fenway opener on October 11, a bejeweled ring finally seemed possible. “In the National League we don’t face anyone who throws a spinning curve that takes two minutes to come down,” observed third baseman Pete Rose after the gyrating Tiant had twisted them into knots, and then touched off a killer six-run seventh with a single off a misplaced Don Gullett changeup.

The Sox came tantalizingly close to winning Game 2, carrying a 2-1 lead into the ninth before the visitors scored a pair of two-out runs off Dick Drago to escape with a 3-2 win. “Nobody said it was going to be easy,” Lynn remarked as the club packed for Cincinnati. “No way.”

Nobody said it would be fair, either. In Game 3, umpire Larry Barnett, misinterpreting the rules, called Fisk for interfering on pinch hitter Ed Armbrister’s 10

th

-inning bunt. The Reds, who’d led 5-1 before a Sox comeback, won it, 6-5, on Joe Morgan’s single. “This is brutal,” declared Fisk. “I never saw anything like it in my life.”

Fortunes were reversed the next night. It took a five-run inning and 163 pitches by Tiant, but Boston hung on for a 5-4 victory. Then came another shift in momentum: Gullett mastered his opponents, 6-2, in Game 5 and the Sox returned home on the brink.

A three-day nor’easter gave them time to regroup and allowed Johnson to start Tiant instead of Lee. “Tiant is our best,” he said. “We’re down 3-2. We have to win the sixth game first.”

It took the Sox until after midnight to do it and Tiant was long gone when they did. But after pinch hitter Bernie Carbo’s two-out, three-run homer in the eighth brought Boston back even, Fisk won it in the 12

th

with a homer that bounced off the left-field foul pole and set church bells ringing in triumph in his hometown of Charlestown, New Hampshire. “I straight-armed somebody and kicked him out of the way and touched every little white thing I saw,” said Fisk after his celebratory gallop around the bases through fans and teammates on his way to touch the plate.

For five innings the next night, the faithful could envision a championship flag flapping as the Sox took a 3-0 lead. But Lee served up a looping, ill-timed “Leephus” pitch with two out in the sixth to slugger Tony Perez, who launched it over the Wall for a two-run homer. “Lee threw it to the wrong guy,” Morgan mused years later. “He could have thrown it to me, Pete Rose, Johnny Bench, anybody. But Perez was the best off-speed hitter on our team.”

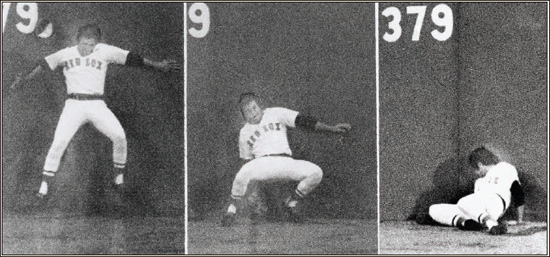

ATTACK OF THE GREEN MONSTER

Game 6 of the 1975 World Series was noteworthy for, among other things, one catch that was made (by Dwight Evans, to steal a possible home run from Joe Morgan in the 11

th

inning) and one that was not (by Fred Lynn when he slammed into the left-field wall in pursuit of Ken Griffey’s two-run triple).

As part of the modifications for the 1976 season, the wall was stripped of its metal skin and fitted with a smoother, Formica-like covering. Protective padding was added to the wall’s base to prevent serious injury, a move swayed at least in part by Lynn’s scary World Series collision.

The new surface made caroms off the wall more predictable, and the Jimmy Fund, the Red Sox-supported charity, was made a little richer. The green sheet metal of the old façade was turned into paperweights and sold to fans to benefit cancer research.

The biggest change, however, was the addition of a huge electronic message board and scoreboard in center field—a first in Major League Baseball. The manually operated left-field scoreboard was reduced in width, with the elimination of the section of the board devoted to National League scores (which would instead be shown intermittently on the message board).

The new scoreboard cost $1.5 million, which was more than the cost of the complete stadium overhaul that took place in 1934. The board was 40 feet wide and 24 feet high, flashed 8,640 lights and was equipped to show both film and videotape, including instant replay.

Did the new scoreboard affect the game? A flagpole stood in center field for much of Fenway history. Jim Rice was the last man to hit a ball completely out of the park in that direction when he homered to the right of the flagpole off the Royals’ Steve Busby in 1975. It’s nearly impossible to do now because of the center-field scoreboard, the 2011 version of which is even larger.

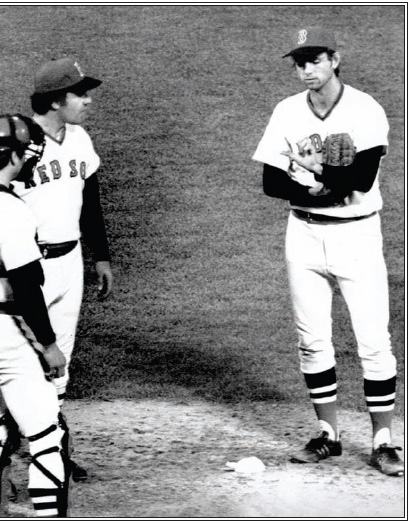

Bill Lee showed teammates Carlton Fisk and Rico Petrocelli the blister on his thumb that would force him to leave Game 7 of the 1975 World Series in the seventh inning. The Red Sox lost the game, 4-3, after holding a 3-0 lead.

Lee left with a blister in the seventh. Then Rose tied it up. After Johnson yanked reliever Jim Willoughby for pinch hitter Cecil Cooper and brought in rookie Jim Burton for the ninth, Morgan won the game and World Series with a two-out blooper to center. “It was a slider low and away, and I couldn’t have asked for a better location,” Burton said as his teammates glumly put on their street clothes. “He didn’t even hit it well.”

The Sox were honored the next day at City Hall Plaza by thousands of fans for their gallant run, but second place in October brings no reward. “We’re going to win that Series yet,” vowed Yastrzemski.

Any chance that Boston had of a reprise vanished early in 1976 when the owners locked out the players in March after the Basic Agreement had expired and Lynn, Fisk, and Rick Burleson held out. “The togetherness, it wasn’t there,” Johnson would say at the conclusion of the club’s most turbulent season in memory. “With those men playing out their options, I could see something was different, right from the start.”

“There’s nothing in the world like the fatalism of the Red Sox fans, which has been bred into them for generations by that little green ballpark, and the wall, and by a team that keeps trying to win by hitting everything out of sight and just out-bombarding everyone else in the league. All this makes Boston fans a little crazy and I’m sorry for them.”

—Bill Lee

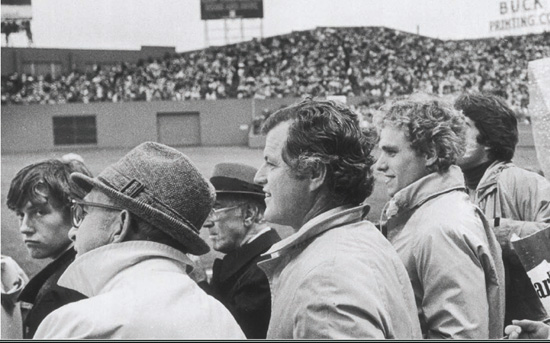

Senator Ted Kennedy and nephew Joe were faces in the crowd during 1975 World Series play.

Resilient Red Sox Nation returned to its “wait till next year” philosophy in the wake of the ’75 loss.

SIZING UP THE WALL

The sign at the base of Fenway Park’s famous left-field wall long indicated that the fence was 315 feet from home plate. Yet, from the day that sign was posted, batters insisted that the wall was less than 315 feet from home plate.

No doubt some of this skepticism was due to the height and breadth of the wall. Its imposing dimensions make it appear closer than it really is. But it turns out there was more to it than perception—there was proof.

In 1975,

Globe

sports editor Dave Smith was presented with aerial photos of the park, accompanied by the report of an expert who flew reconnaissance in World War II. The military man concluded that the distance from home plate to the left-field wall was 304.779 feet. Smith made a formal request to the Sox to have someone from the

Globe

measure the foul line. The team refused to comply, and the next day it was Page One news in a story by Monty Montgomery. Original blueprints from the Osborn Engineering Co.—which built Fenway in 1912—indicate that the wall is 308 feet from home plate.

Citing various reasons, the Red Sox for years had been reluctant to let anyone measure the debated distance. It was part of the Fenway mystique. Author George Sullivan once used a yardstick and came up with a distance of 309 feet 5 inches. It turns out that Sullivan was darned close.

One day in March 1995, in broad daylight, armed with a 100-foot Stanley Steelmaster measuring tape, the Globe’s Dan Shaughnessy vaulted the railing and measured the line. He found it to be 309 feet 3 inches, give or take an inch, and he said so in a story on April 25. In May, the Red Sox surreptitiously admitted to their longstanding fib. Groundskeeper Joe Mooney re-measured the distance, and after huddling with Sox management, quietly changed the numbers on the wall to “310” feet. For a while, it went unnoticed.

“I was sitting in the stands before the game wondering when someone would come up and ask about it,” said Mooney later. “Nobody did.”

When Shaughnessy’s estimate of 309 feet 3 inches was mentioned, Mooney said, “That’s about what it is. We rounded it off. It came out in that story, so why hide it?”

After all those years, why indeed?

Even at 310 feet, Fenway’s dimensions would be against the rules if the ballpark were being built today. The league now stipulates that fences must be no less than 325 feet from home plate.