Fields of Home (12 page)

13

The Horsefork Works

F

OR

the next two weeks, Millie and I were busy from the time we could see in the morning till we couldn’t keep our eyes open at night. I strung the horsefork up again, and we taught Old Nell to pull the tote-rope without being led. Millie learned to set the horsefork, and I stowed the hay away in the mows. The weather stayed good, and we alternated: mowing and raking in the forenoons, and hauling as late as we could see in the afternoons. That gave Millie the mornings to do her housework and take care of Grandfather, and it let us do the hauling when the hay was driest. By sharpening mowing machine sickles and making repairs in the evenings, I didn’t have any trouble with the equipment, and always had dry hay ready for hauling in the afternoons.

Grandfather was our biggest worry. It wasn’t his sickness that worried us; it was his getting better. He seemed to have been right about Millie’s being able to take care of him as well as a doctor. After the first four days, we could never tell when he’d get up and come outdoors.

Almost every morning, he’d get up and have breakfast with us, then he’d often fuss around the bee shop or the hives for an hour or two. Sometimes he’d walk out as far as the pasture with Old Bess at his heels, but we never saw him go to the barn, and he’d usually be back in bed before noon. When I’d finished with the horserake, I always backed it into the chockecherry thicket at the foot of the orchard. Once we watched him walk within ten feet of it, but he didn’t look that way, and the mornings that I used it were the ones when he worked in the bee shop.

One day, early in our second week, Grandfather came out to Niah’s field while we were loading. He didn’t offer to help, but either sat on a shock or poked around the stonewall, hunting for a ground-hog’s hole. When the rack was piled so high I could hardly reach the top, he wandered toward the house. Millie stood on the load watching him as he climbed the high end of the wall, crossed the dooryard, and went into the house. “What in tunket do you cal’late’s got into Thomas?” she asked me. “He ain’t no sicker’n I be right this blessed minute, and there he goes, leaving us to do all his haying for him while he lays abed. I do declare! I never seen the beat of the man in all my born days. First off, he worries hisself sick abed ’cause the hay won’t be in afore the Fourth, and now he stays abed so’s there ain’t no chance of it.”

“Keep your fingers crossed,” I told her. “If he’ll keep on playing sick four more days, we’ll just about have the haying licked, and the Fourth of July is nearly a week away. Unless it rains, or Grandfather catches us using the horsefork, the last forkful should be on the mows by sunset of the second.”

On the morning of the second, I was sure our luck had run out. The sky at sunrise was as red as fire, and anyone could have told there’d be heavy rain long before the day was over. Grandfather was as fidgety as an old mare. He called me when the first streaks of pink showed above Hall’s hill, and he fretted about one thing or another all through breakfast. “Get your hosses out! Get your hosses out, whilst I take the cows to pasture!” he snapped at me before I’d finished eating. “Time flies, and there’s rain a-coming on! We’ll have to stir our stivvers afore it gets here!”

Millie pushed her chair back, took her cup, and went to the stove. She looked frightened and, as she poured tea into the cup, she was shaping words to me with her lips. I couldn’t make out what she was trying to say, but it didn’t make any difference, so I just turned the palms of my hands up. The barn was stuffed nearly to the peak. Instead of leaving pitch-up landings, we’d built the mows well out over the driveway in the center of the floor. There was no way of putting more hay up, except with a horsefork. Sooner or later, Grandfather would know we’d been using it all the time. He might as well know it now. He had better sense than to think we’d been pitching hay thirty feet straight up into the air.

I went to the barn, turned the cows out, and called to Grandfather that they were ready to go to pasture. Then I harnessed the horses, called Millie, and we drove to the high field.

I’d left the high field that had all the rocks on it till the last. It had the poorest hay on the place, and was the farthest from the barn, way back by the beech woods. Millie always helped me pitch till the load was above the rails on the hayrack. That morning, the shocks were dripping wet with dew, so I set her to skinning the tops off them while I pitched the dry hay from underneath. We’d just made a good start when there was a yoo-hoo from down in the valley, and I looked over the brow of the hill to see Annie waving to us from Littlehale’s pasture gate. I forgot all about Grandfather, or Millie, or haying, and just stood there, watching Annie and waving my hand, but she didn’t wave again. She just put up the pasture bars, and walked back along the lane toward Littlehale’s house. I felt kind of silly, because I was still standing there, watching her go and flapping my hand a little when from right behind me Grandfather said, “Come on, Ralphie! Come on! Don’t stand there dawdling all day! There’s rain a-coming tarnal soon.”

Grandfather’s sickness seemed to have done him a lot more good than harm. He didn’t tire nearly as soon from pitching, and even with the rain coming, he acted a lot happier than I’d ever seen him. He pitched steadily until the load was about as high as he could reach, and he only got mad once. That was when I said the field looked to me like awfully good strawberry and tomato ground. He called me know-it-all and bigheaded, and said he didn’t need me or anybody else telling him how to farm. In less than two minutes he was all right again, and sang out, “Gorry sakes alive, Ralphie, don’t seem like it’s took us no time at all to pitch on this load. There! That’s just about as high as your old grampa can histe it. You finish it on out whilst I go look at my ground-hog trap. I’ll catch up with you children at the barn.”

Millie began worrying and stewing as soon as we started driving to the barn. “Thomas will skin the both of us alive soon as ever he lays eyes on that cussed horsefork,” she fretted. “Like as not he’ll run you off the same way he done with Levi.”

I was still sore about Grandfather’s calling me know-it-all and bigheaded, and I told her, “You don’t need to worry about it. The horsefork was my idea in the first place, and it still is. I’ll take the blame for it. How much of this hay do you think we’d have put up without it? Let him run me off if he wants to; he’ll never be able to say I didn’t do a good job for him. What difference does it make now? With nothing but hay on this place, he doesn’t need me any longer, and I’ll go where people don’t think I’m bigheaded. There are only two more loads left in the field, and one wetting won’t ruin it.”

“Ain’t there no way we can pitch what’s left up by hand?” Millie asked. “If he don’t have to see the cussed thing, maybe we can finish up without no trouble.”

“I want him to see it,” I blurted out. “I want him to know that he’d have lost most of his hay if we hadn’t used it.” Millie took hold of my arm, and her voice was pleading when she asked, “You ain’t going to point it out to him, be you, Ralph? Don’t start no row with him. Thomas, he can’t abide to be crossed, and he’d run you off for certain.”

I didn’t want Millie to feel badly, and though I didn’t believe it, I said, “Don’t worry, Millie; just keep your fingers crossed. He’s as sick today as he has been any day in the last week, and maybe he’ll go back to bed before he catches us.”

“Ain’t there no way we can pitch it up by hand?” she asked again.

“Not a way in the world,” I told her. “We’ll have to use the horsefork, but I won’t point it out to him. If there’s going to be any row, he’ll have to start it.”

As we pulled into the dooryard, we could see Grandfather and Old Bess way off at the far side of Niah’s field. They were beyond where he’d set the ground-hog trap, and were poking along the stonewall toward the woods. Millie didn’t say a word, but she held her hand up in front of my face, and her fingers were crossed.

We didn’t see anything more of Grandfather till we’d finished unloading, gone back to the field, and had the next load half pitched on. He came out of the beech woods, and hurried toward us so fast that Old Bess had to trot. “By thunder, Ralphie!” he called as he came. “Cal’late I and Old Bess has found the boar ground-hog’s hole. All-fired great big one! Under the stonewall down nigh the twin pines. Tarnal, pesky critter! Been hunting his hole ever since the snow went off last spring. Gorry sakes alive! Didn’t cal’late on running off like that and leaving you children to do all the work. Did you take note where I left my pitchfork?”

We’d finished the pitching, unloaded, and were back in the field before Grandfather found where he’d left his pitchfork in the woods. Until there were only three or four shocks left in the field, he alternated between pitching hay and telling us about all the woodchucks he and Old Bess had caught. Then he stopped, looked down at the beech woods, and said, “Gorry sakes! That’s where I ought to have my trap sot, ’stead of over in Niah’s field. Did ever you eat woodchuck, Ralphie? Just as good as hen, any day. Cal’late I’ll go move the tarnal trap afore the rain comes. Go on to the barn whenst you’re done; I’ll be along in a jiffy.”

It was a long jiffy. During the time Grandfather had been sick in bed, we’d worked the tote-rope horse out through the back barn doorway, so he wouldn’t see her from the house. That morning with him in the fields, we had to work the other way, into the dooryard. Old Nell was making the last pull on the last forkful from the last load of hay on the place, when I looked through the swallow hole in the peak of the barn. Grandfather and Old Bess were halfway down the orchard hill, and coming fast.

I jerked the trip cord the second the horsefork came over the edge of the mow, called Millie to unhook Old Nell and get her hitched back to the hayrack. Then I unfastened the rope from the big fork, left it lying where it fell on the top of the hay, tied the loose end around my waist, and slid down the tote-rope to the barn floor. Millie had Old Nell hitched back to the hayrack by the time I’d hauled the rope end through the block on the ridgepole. We gathered up rope, pulley blocks, and whiffletree, stuffed them into the grain bin and slammed the cover down. When Grandfather climbed up over the yard wall, we were backing the hayrack out of the barn floor. The only signs of the horsefork were the empty pulley block hanging high on the ridgepole, and the path Old Nell made in pulling the tote rope.

For the first time since Grandfather had taken sick, he walked in through the big front doorway of the barn. He didn’t look up till he was standing right in the middle of the barn floor. For at least a full minute, he just stood there with his head turned back, his hat in his hand, and his mouth wide open; looking up through the narrowing cone of the mows. “Gorry sakes alive! Gorry sakes alive!” he said, half aloud. Then he swung around to Millie and me as we came back to the doorway. “Good on your heads, children! Good on your heads!” he sang out, ran and threw an arm around each of us. “How in the great thunderation did ever you . . . Bless my soul! Never seen the old barn stuffed so full in all my born days. Gorry! Wisht Levi was here to see it. Provender enough to winter twenty head of cattle! Ralphie, your old grampa’s proud of you, boy. And you, too, Millie girl. How in the great . . . ” As he talked, he had led us in to the middle of the floor, stopped, and stood looking up toward the peak of the barn.

I felt pretty good myself, but I think Millie felt even better. There was pink in her cheeks when she pushed her sunbonnet back, and her eyes were bright. “’Twa’n’t nothing,” she told him, laughing, “but don’t you get no ideas about me milking twenty head of cows, come winter. We done it so’s you could go to the reunion off to Gettysburg.”

“Foolishness! Foolishness!” Grandfather snapped out, but there wasn’t much edge to his voice. “Ain’t going off frittering away nigh onto a week’s time whilst there’s yet the dressing to be spread. Ralphie, I and you’ll . . . ”

I cut in on him, but I’d only got as far as “I’ll take care of the . . . ” when a quick blast of wind swept through the barn. Lightning and thunder both struck together and, for a moment, I was afraid the buildings had been hit.

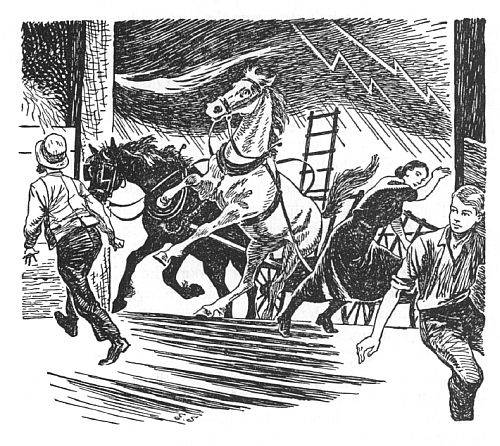

When we’d backed the hayrack out, I’d left the horses standing faced toward the barn doorway. With the crash of thunder, the yella colt came tearing in, dragging Old Nell and the hayrack after him. We all had to dive to keep from being run over. When Millie and I scrambled to our feet, water was pouring down as if the barn had been under Niagara Falls, the yella colt was dancing a jig, and Grandfather was lying almost under his hoofs. He rolled away, sat up, and he seemed to be looking at something far away, through the open doorway of the barn. “By fire!” he sang out. “Just like the battle of Gettysburg; guns a-blasting, fire a-spurting out, hosses a-running and stomping, and the rain a-pelting down. Gorry sakes, Ralphie, do you cal’late you and Millie could look after the farm if I was to go off to the reunion?”

It wasn’t a very busy afternoon for me. The shower settled into a steady rain, and I spent most of my time mending harness and cleaning the bench in the carriage house, but Millie was as busy as a beaver. She heated water for Grandfather’s bath, cleaned his Sunday suit, and packed his old valise, while he fussed around like a hen with one chick. He got soaking wet when he went out to tell the mailman to pass the word about his going to the reunion. And it was nearly nine o’clock before Millie could get him to stop telling army stories and go to bed.