Fields of Home (3 page)

I scrubbed until I was redder than fire, dried myself, pulled on my clean clothes, emptied the tub, and hurried to the kitchen door. From what I’d already heard, I expected to find Grandfather and Millie at each other’s throats, but they were both at the table and seemed as happy as a couple of birds in the spring.

“Come right in, Ralphie! Come right in!” Grandfather called. “Millie baked us a nice good sugar cake for dinner. Never see ary woman could bake a better sugar cake than Millie.”

Anyone could have seen that Millie liked to have him say it, but she stuck her nose up a little, and said, “’Taint up to my usual. Devilish Getchell birch I been getting for firewood ain’t fit for fence rails. Got to stand and blow on it to get spark enough to melt grease.”

The dinner was boiled potatoes and fried salt pork, just as Mr. Swale had said it would be, but there was plenty of it and it was good. Grandfather talked more than he ate, and he kept his knife waving as he talked—sort of like a band leader. Two or three times, he dropped the piece of pork he had balanced on it, and then put the empty knife into his mouth. “Gorry sakes alive, Millie,” he said, “with Ralphie here to help us, I cal’late we’ll have the hay a-flying like goose feathers. Wouldn’t be a mite surprised if we had it all fetched home to the mows afore company reunion time. Ain’t been to a reunion since . . . Gorry sakes . . . Ain’t been since the first year you come; the summer Levi was to home. Wisht Levi’d come down this summer.”

He sat looking at his plate for a minute, then his head jerked up, and he said, “Eat your victuals! Eat your victuals, Ralphie! Cal’late to get a start on the orchard hay this afternoon. I’ll go provender the hosses.”

3

The Yella Colt

I

HADN’T

half finished eating my dinner when Grandfather left the table. From what he’d said about his going to feed the horses, it didn’t seem to me I’d have to hurry. I knew it would take them half an hour to eat, and I was still as empty as a last year’s gourd. I’d just reached for another potato when Millie said, “Better get them victuals into you as fast as the Lord’ll allow; your grandfather won’t put up with no dawdling ’round the house.” I ate so fast I got a lump under my wishbone and hurried after Grandfather.

I’d worked plenty in the hayfields in Colorado. When I was only eleven years old and weighed seventy pounds, I’d been paid a man’s wages for running a horserake or mowing machine. Father could always pitch more hay in a day than any other man in the neighborhood, and he’d taught me the tricks when I was little. Out there, we’d put up stacks of hay that had more than a hundred tons in each one of them, and I wanted to show Grandfather that I knew just how every part of it was done.

He wasn’t anywhere in the barn. There were box stalls just inside the big doors. As I passed the first one, a buckskin horse poked his head out and snapped at me. His ears were pinned back tight against his head, white showed around his eyes, the way it does on a fighting stallion’s, and his whole muzzle was peppered with gray hairs. There was a fat sleepy-looking bay mare in the next stall. She didn’t bother to raise her head from the feedbox when I stopped at the doorway of her stall, and I only stopped long enough to notice that she was just fat instead of with foal.

There was a sow, nursing a litter of new pigs, in the next stall, and the rest of the main floor was empty. Pigeons were cooing somewhere in the high loft and, as I looked up, a barn swallow swooped from its mud nest on the ridgepole and glided out through the open doorway. There was the smell of new hay in the barn, but I could only see a fringe of it hanging over the edge of a low mow. On the other side, over the box stalls, the mows were filled to the rafters with bleached hay that looked to be two or three years old.

I thought Grandfather might have gone to the barn cellar, so I jumped down over the wall and went to see. He wasn’t there, but the hog was. I could hear him grunting, back in the darkness. I went in, and kept my eyes closed till I could see in the dimness. In the center of the cellar, there was a pit about thirty feet square. It held a brownish pond, with a mountain of manure in the middle. There was a two-foot path around it, and, back against the walls on the three sides, there were rows of pigpens. On one of them the gate was broken and lying, half buried, at the edge of the pond. I fished it out and propped it across the path beside the open pen. Then I shaded my eyes, went out, and came in on the side of the pit where the hog was. He didn’t give me a bit of trouble. As I went toward him slowly, he looked up from his rooting, grunted a couple of times, then turned and walked along the path. When he came to the open gateway, he went in.

I hadn’t seen or heard anything of Grandfather since he’d left the dinner table. After I’d wired the gate into place, I decided to go and look at the horses again. As I was going through the big front barn doors, I heard Grandfather holler from behind me. He had on a wide-brimmed straw hat with a big white veil, and was down at the beehives under the apple trees. “Take care, Ralphie! Take care the yella colt!” he called as he came scrambling up over the dooryard wall.

I hadn’t seen any colt when I’d been in the barn before, but I was glad to hear there was one. While I was waiting for Grandfather, I was thinking how much fun it would be to harness-break a colt. I hoped he might be old enough to ride. Grandfather pulled the bee hat off as he came, and dropped it by the pile of cordwood at the top of the wall. “Afore we start to haying, we got to get that tarnal pig in,” he called as he came toward me. “Can’t find hide nor hair of the pesky critter nowheres.”

“He’s back in his pen,” I told him. “The gate’s broken, but I wired it up so it will hold till we can make a new one.”

Grandfather stopped in front of me and looked up with a scowl, as though he thought I were lying to him. “Who put him in?” he asked.

“I did.”

“Who helped you?”

“Nobody.”

“How’d you do it? I and Old Bess has been trying to catch him for a week.”

“By not yelling at him,” I said.

Grandfather’s face flared red. He jerked his head back so that his whiskers stuck out at me, and shouted, “Don’t you . . . ” Then he stopped, and just stood staring right into my eyes for a full minute. I didn’t stare back, but I didn’t look away from his eyes. When I was beginning to wonder if we were going to stand there looking at each other all afternoon, he said, gruffly, “Now stand back out the way! The colt ain’t been used of late and he’s high-strung. Most likely he’d bite you or tromp on you.”

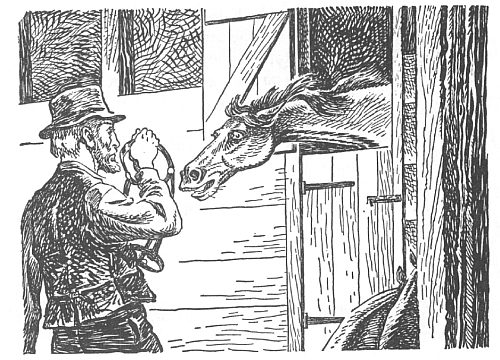

I didn’t wonder the colt was high-strung. Grandfather took a bridle down from the wall, and began shouting, “Whoa! Whoa, boy! Whoa! Whoa!” The thing that did surprise me was that he started for the first box stall. That was the one where the buckskin was. I hadn’t looked at his teeth but there hadn’t seemed any sense in doing it. From the way his eyes were sunk back into their sockets, and from the white hairs on his neck and cheeks, I’d known he was as old for a horse as Grandfather was for a man.

The old buckskin didn’t wait for Grandfather to go into the stall. His head shot out above the half-door. It was straight out from his neck, his ears were pinned back, his teeth bared, and he struck both ways like a coiled rattlesnake. Grandfather held the bridle up in front of his own face, and shouted, “WHOA! WHOA, BOY! Whoa, whoa!” On the next swing of his head, the old horse grabbed one of the bridle blinders in his teeth and shook it. Then he let go, jerked his head out of the doorway, whirled, and clattered to the far corner of the stall. I could see it was nothing new with him, because the bridle blinders were frayed, and ridged with toothmarks.

Before I stopped to think, I said, “Let me have it; I’ll harness him.”

Grandfather’s head swung at me the way the buckskin’s had swung at him. “Stand back! Stand back, I tell you! Ain’t you got brains enough to see he’s a dangerous hoss?”

I did step back to where I had been, but as I stepped, I said, “Give him something hard to bite on and he’ll quit that snapping.”

Grandfather jerked his head toward me again, and his face was fire red. “Mind your manners!” he snapped, and then reached for the hasp of the half-door.

I was really afraid to have Grandfather go in there. The old horse swung his hind end to whichever side Grandfather tried to get past, and he was kicking like a cow with a sore teat. Each time he kicked, Grandfather would jump back and holler, “Whoa! Whoa, you tarnal fool colt!” For the first minute or two, my heart was pounding as hard as the buckskin’s hoofs. I grabbed up a pitchfork and got ready to make a rush if there was any real danger. Then I had trouble to keep from laughing. It was all a show with the old horse, and Grandfather should have known it. Hard as he was kicking, the buckskin was careful to miss Grandfather by at least a foot with each hoof and, with all his slatting his rump around, he never came close to squeezing Grandfather against the sides of the stall. I don’t know how long it might have gone on if Grandfather hadn’t lost his temper. He swung the bridle up over his head and whanged it down across the buckskin’s rump. The old horse crowded over against the far wall, and stood shaking all over, as if he were frightened to death.

Grandfather didn’t shout after he’d hit the horse, and his voice was almost petting as he inched slowly forward. “Tarnal fool! Tarnal fool hoss! Must always I have to hurt you afore you’ll behave yourself? Poor colty! Poor colty! Whooooa, boy!”

As soon as I saw that everything was going to be all right, I stood the pitchfork down and stepped back to where I’d been in the first place. I was hardly there before Grandfather shouted, “Whoa! Whoa, boy!” again, and led the buckskin out of the stall. With the sound of his voice, the old horse’s hoofs began to beat again, and he came out like a prize stallion into a show ring. “Stand back! Stand back, Ralphie!” Grandfather shouted. “Don’t get next nor nigh his heels! He’s dangerous, I tell you!”

4

The Mowing Machine

I

’D HANDLED

some pretty mean horses on ranches where I’d worked in Colorado, and was itching to get my hands on the yella colt, but Grandfather wouldn’t let me go near him. The old horse would jig in the same spot till Grandfather had the harness chest high, then he’d shy away, and Grandfather would chase after him, shouting, “Whoa! Whoa, you tarnal fool colt!” I’d given the bay mare a good combing and brushing, and had her harnessed before Grandfather cornered the yella colt. “There, by gorry! There you be, Ralphie!” he sang out as soon as he’d buckled the crouper. “Colt’s awful high-strung. Got to handle him gentle, elseways you’d never get a harness on him. Been spoilt by them cussed worthless hired hands. Don’t none of ’em understand a high-strung hoss critter. Now you run fetch the snath and scythe out the carriage house whilst I’m hitching the hosses to the mowing machine.”

I’d never even heard of a snath, let alone knowing what it was, and I didn’t think I’d heard right that time. “What is it you want me to get?” I asked.

“Snath and scythe! Snath and scythe!” Grandfather shouted. “Why don’t you listen when I speak to you?”

“I did listen,” I said, “but I don’t know what a snath is.”

“Great thunderation!” Grandfather hollered. “Don’t know what a snath is! Don’t know much of nothing, do you? Didn’t your father learn you nothing about farming?”

“Father taught me plenty about farming, and about handling horses, too,” I said, “but we never had anything called a snath.”

Grandfather dropped both hands to his sides, and just stood looking at me for a minute. When he spoke, his voice was as gentle as a woman’s. “Gorry sakes alive, Ralphie! Your old grampa’ll learn you how to farm. Poor boy! Tarnal shame Charlie died afore he had you half fetched up. Awful good man, Charlie. Shame Mary had to lose him when there’s so cussed many worthless men in the world. Now you run along and fetch the snath and scythe.”

I knew what a scythe was all right. Father used to have one when we lived on the ranch. When I got to the carriage house, there was a scythe about like Father’s hanging on the far wall. I took it down and looked all around to see if I could find anything that might be a snath. I was still trying when Grandfather called, “Ralphie, what’s keeping you? We ain’t got all day!” I grabbed up a broken whetstone, took the scythe, and hurried down behind the barn where he was shouting, “Whoa! Whoa, back!” at the horses.

From the corner of the barn, I could see Grandfather down on his hands and knees behind the yella colt. The colt was the off horse—the one on the right-hand side of the pair—the cutter bar of the mowing machine was down, and, if the team had started up, Grandfather would have been right in the path of the knives. I began to run, but the crooked scythe handle kept bouncing around on my shoulder, and I was afraid I might startle the horses, so I had to slow down. Grandfather looked up just when I was back to a walk, and shouted, “What in time and tarnation ails you? Dawdling away the whole day when there’s work to be done! What kept you?”

“I couldn’t find the snath,” I called back.

I was getting close enough that Grandfather didn’t have to shout, but he snapped, good and loud, “Couldn’t find it! Couldn’t find it! What in thunder you got over your shoulder?”

Of course, by that time I knew it had to be something to do with the scythe, so I asked, “Is it a part of the scythe?”

Grandfather stood up on his knees, with his hands drooped in front of his chest—just the way a prairie dog stands by his hole—and he looked up at me as if I were some kind of a strange animal. “Gorry sakes alive!” he said at last. “How did ever a boy grow up to your age and know so little? Poor boy! It’s a good thing Mary sent you. Your old grampa’ll learn you to be a man. Snath is the handle; scythe is the blade that goes on it.”

Grandfather had the buckskin’s tug wired to the singletree with a piece of rusty old barbed wire. It was so brittle that one strand had cracked where the sharp bend came, and an end three feet long was trailing on the ground. He grabbed the trailing piece in both fists, and bent it back and forth till it broke, leaving an eight-inch spike sticking out with a barb at the end.

“That won’t work very well, will it?” I asked. “One strand is already broken, and the dragging end will ball hay up in front of the cutter bar.”

“Don’t you tell me!” Grandfather blurted, but I knew he could see I was right. As he got up off his knees, the toe of his boot caught the spike of wire and turned it up so it wouldn’t drag. “Ain’t nothing the matter with that,” he said as he climbed up onto the mowing-machine seat. “Now pass me them lines, and stand back so’s you don’t get hurt. Whoa! Whoa, colty!”

I knew quite a little about mowing machines. Father had fixed the machinery for most of the neighbors we had in Colorado, and, if I wasn’t in school, he’d always let me help him. He’d traded a colt for an old secondhand mowing machine one winter, and we’d taken it all to pieces, made some new parts, and put it all together again. When Father got done fixing any piece of machinery it had always worked just as well as a new one. I hadn’t had much time to look over Grandfather’s machine, but in one glance I could see that it was in worse shape than the one Father got for the colt. The cutter bar was lying in a tangle of matted clover, two of the knife sections were broken in half, and one was missing altogether. The gears were out of mesh, and there was new red rust on all of them and along the sickle blades. If the team was started with the cutter bar dragging, I knew it might tear things all to pieces.

The yella colt had begun prancing the minute Grandfather shouted, “Whoa, colty!” I snatched up the reins, but before I passed them to Grandfather, I said, “Hadn’t I better put the cutter bar up before it drags and breaks something?”

“Leave be! Leave be!” Grandfather shouted. “Pass me them reins and stand back out the way!”

I should have kept quiet but, as I passed him the lines, I asked, “Hadn’t I better get an oil can?”

“Stand back! Stand back, I tell you!” Grandfather snapped. Then he spanked the reins up and down, and shouted, “Gitap! Gitap!”

The bay mare didn’t move an inch when Grandfather shouted, but the yella colt went off like a skyrocket—and in the same direction: straight up. He danced a jig on his hind feet, and kept his front ones pawing up and down like a swimming dog’s. When he came down, he rammed into the collar and, of course, broke the rotten old piece of barbed wire on the whiffle-tree. It held just long enough to lurch the mowing machine forward a few inches and make the slipping gears scream. With his outside tug loose, and the screech of the gears behind him, the old buckskin swung around like a slammed gate. He nearly pulled Grandfather off the seat, broke one of the reins, and tore most of his harness off.

Instead of being mad at the yella colt, Grandfather began yelling at me, “Tarnal fool boy! You scairt him! You scairt him! Why didn’t you stand back like I told you? Whoa, colty! Whoa!”

Grandfather was still pulling on the unbroken line. With the yella colt turned around facing him, and with the line through the ring on the harness, it only made the horse pull back harder. “Let go of the line!” I shouted, as I ran toward the buckskin.

“Shut up! Shut up! Get out of the way!” Grandfather yelled back, and kept right on pulling. The collar was hauled tight up around the old horse’s jaws, and he had his feet braced the way a bulldog does when he’s trying to pull a stick out of your hands. I still had the scythe stone in my hand, had got back of the yella colt, and was just ready to hit him and make him jump forward, when the second rein broke and the buckskin sat down with a thud. His rump missed my feet by less than two inches, and Grandfather hollered, “Now see what you done! Why didn’t you keep out the way?”

Grandfather came up and began patting the old horse on the neck. “Poor colty! Poor colty!” he said soothingly. “Tarnal nigh busted the harness all to smithereens, didn’t you? Ralphie, I and you’d better fetch it up to the carriage house and fix it. Awful high-strung hoss, the yella colt. Did you mark any harness rivets laying ’round the bench? Plenty of ’em in Levi’s drawers, but he gets so all-fired het up if I pry one of ’em open. Wisht Levi’d come home.”

“What does Uncle Levi do in Boston?” I asked him.

“Brick mason, but he ought to be a tinker or a blacksmith, and he ought to be right down here to home where he belongs. Levi ain’t no more of a farmer than you be, but he can mend anything he puts his hand to and, by gorry, there’s plenty stuff around here that needs mending.”

Grandfather turned away from the yella colt and pointed toward a jumble of wrecked carts, buggies, and farm machines that lay half buried in a weed patch beyond a shed built back into the hillside. “Made some powerful good trades enduring the last two–three years. Yonder, past the sheep barn, there’s stuff enough to keep Levi out of mischief four–five months. Fetch a pretty penny whenst it’s all mended up nice. Now you lug the busted harness up to the carriage house, Ralphie. I’ll stand the yella colt back in his stall so’s he don’t stave Nell’s harness whilst we’re gone. Tarnal high-strung hoss! Can’t never tell what he’s likely to do.”

All the time Grandfather had been telling me about Uncle Levi and the machinery, the old buckskin had been sitting on his haunches. His collar was pulled up behind his ears, so that his head was stretched out almost straight, and the broken harness was hanging from it. I stepped up to unbuckle the hame strap and let him loose, but Grandfather hollered for me to stand back before I got hurt. Instead of unbuckling the strap himself, he began spanking the old horse on the rump with his hand, and saying, “Get up, colty! Get up, get up!”

“He can’t get up without raising his head,” I said. “You’ll have to unbuckle the hame strap.”

“Stand back! Stand back! Don’t you tell me! Get up, colty! Get up, get up!” With the last, “Get up,” Grandfather whacked the old horse a good one, and he thrashed around until he’d thrown himself flat. All four legs were going as if he were trying to run a two-minute mile right there on his side, and Grandfather was dancing in and out between the flying hoofs and shouting, “Whoa, colty! Whoa! Whoa, I tell you!”

The yella colt’s back was toward me. I stepped in quick, yanked the end of the top hame strap, and let it slip out through the buckle. The hames flew off the collar as though they’d been pulled by a spring, and the horse flopped his head down and lay as if he were dead. “Now see what you done!” Grandfather yelled at me so loud his voice went squeaky. “You killed him! You killed him!”

I’d taken all the blame I could stand. Anybody who knew anything about horses could see that the buckskin was only sulking, and that he wasn’t hurt a bit. I was so mad about Grandfather’s yelling at me that I wanted to throw something at him, and I still had the broken piece of whetstone in my hand. Before I even stopped to think, I smacked it down hard on the old horse’s rump. He came to life quicker than a scared jackrabbit, and scrambled to his feet. Then he stood there trembling all over, while Grandfather scolded me. “Don’t you durst! Don’t you

never

durst hit a dumb critter!” he shouted. “Poor colty! Poor colty! Now fetch that harness up to the carriage house whilst I take him to the barn.”

I gathered up the harness, and watched Grandfather take the old buckskin to the barn, or rather, the buckskin take Grandfather. The yella colt was all of sixteen hands high, and carried his head like a giraffe. Black spots were all he needed to make him look like one. Grandfather had the bit ring clutched in his fist, and was being jerked to his tiptoes as the old horse pranced and flung his head. All the way up through the barnyard, he was dancing around, trying to keep his feet out from under the horse’s hoofs, and shouting, “Whoa, colty! Whoa, you tarnal fool hoss!”

We didn’t get along much better mending harness than we had in breaking it. Father had taught me how to set a rivet tight by driving the washer down with a small nut, then cutting the tail close and tapping it evenly with a hammer. The only rivets we could find on the bench were three-quarters of an inch long, and the washers were too big to fit them. I tried to show Grandfather how to split a rivet end, spread it both ways and tap it flat, but he snatched the hammer out of my hands. “Great thunderation!” he snapped. “You’re worse than Levi! Fiddle-faddle ’round half a day putting in a harness rivet! Stand back whilst I fetch it a clip!” He swung the hammer higher than his head, pounded it down like a sledge, and mashed the long rivet into a flat figure S. “There, by thunder!” he said, as he looked at it. “Ain’t no reason that won’t hold tight as a button. Now find me three, four, half a dozen more of ’em. Your old grampa’ll learn you how to be a farmer yet, Ralphie.”