Final Patrol (19 page)

Authors: Don Keith

Kiyoshi and the other children had to climb aboard fishing boats and were floated a few at a time out to the huge transport. Along the way, he saw some of his teachers, several members of families he knew, and other students from his school. They were all laughing, excited about sailing away on such a big boat.

Kiyoshi and his classmates were shown to one of the lower cabins, where tiny beds seemed to fill every inch of the stuffy quarters. They were given small boxes that contained food for the trip. Life vests were given to each of them, along with quick instructions on how to strap them on if there should be an emergency. The young boy looked at the contraption for a long time. It was the first time he had thought of the possibility of the ship sinking, of their not making it across the sea to Japan. But how could such a massive vessel sink?

His thoughts were interrupted by bells ringing, whistles blowing.

Then they were off.

On the second night of their voyage, Kiyoshi and a friend finally gave up trying to sleep in the stifling little room they shared with all the other student passengers belowdecks. The games they played did not help either, and some of the other children fussed at them for keeping them awake. They took their blankets, food boxes, and life vests and went to the ship's main deck to try to find a cooling breeze.

Though not nearly as bad as it was in the cabins below, it was sweltering topside as well. Still, with the gentle rolling of the ship and a humid, fitful breeze in their faces to help make the air bearable, he and his friend were soon able to find sleep.

A thunderous, dull

whoomp!

woke them with a start. The deck of the big ship improbably shuddered beneath them. It was surreal. How could such a big ship tremble so?

whoomp!

woke them with a start. The deck of the big ship improbably shuddered beneath them. It was surreal. How could such a big ship tremble so?

At first, Kiyoshi thought it was a dream, but the shrill, panicked shouts around him brought him out of the fog of sleep at once. Something had happened to their ship. Something awful.

“Get ready for jumping!” a sailor screamed at them as he ran past, and then he sprinted on down the deck, rousing others who had come topside to sleep in the cooler air. “Hurry! The ship will sink! Get ready to jump!”

But Kiyoshi did not wait for any order to jump into the sea. If the ship was going to sink, it would do so without him still aboard.

Besides, he could already see blazes and was choking from all the acrid smoke. And there were screams. Screams of panicked, hurting people coming from somewhere beneath them, from the lower decks of the ship. Kiyoshi wondered for a brief moment how they would all be able to get up the ladders to the deck to get off the ship. Wondered about his friends and classmates and teachers.

But he sensed he did not have time to wonder for long. Using the flickering light from the flames that climbed up the side of the ship behind him, the youngster strapped on his life vest, just as he had been instructed to do, held hands with his friend and another student, stepped through the railing, and jumped from the already listing ship.

The fall was not nearly as far as he expected. It seemed that they were in the sea almost immediately.

And once they landed in the surprisingly cold water, they swam as hard as they could. Instinctively they knew that it would be best for them to get as far from the sinking vessel as they could. Somehow they knew there was a danger that they would be sucked down with her.

As they swam away from the flames, the smoke, the screams and shouts, they sang songs, the ones taught to them by the teachers when they were back at school in their hometown. Many of the teachers who taught them those songs were aboard the ship with them. They were songs of glory, of dying to serve the emperor if called upon to do so in order to make a stronger empire.

Their voices sounded eerie and hollow to them. There was no echo on the rolling sea waves. The words and tune were seemingly gobbled up and swallowed by the black night. They sang anyway. They dared not look back as explosions continued behind them, the brightness flickering like close-by lightning strikes, the blasts rolling across the water, stunning their ears.

Surely someone would soon pick them up. Several naval vessels were escorting them. They had seen them from the decks, wallowing along all around them.

But no one came.

Then, almost lost in the smoke and darkness, a small bamboo raft came floating near. Kiyoshi and his friend climbed aboard, joining two other survivors who had made it off their ship.

It was a terrible ordeal. A typhoon was nearby so the water was rough, bouncing them sickeningly from wave trough to high in the air on a peak. Yet it did not rain. There was no water to drink.

After several days on the raft, Kiyoshi hallucinated, believing he could stand, walk off the raft, and go find a cool, bubbling spring. There he could finally drink his fill. One of the other people on the raft slapped him hard and convinced him he must stay put, that there was no cool spring. Later, they drank their own urine to survive. They managed to catch a small fish and the four of them shared the meager morsel.

Still no one came.

When the sun was up, they could see the sharks, slowly circling the raft. One of the boys used a sharp stick he had salvaged from the sea to poke at them. Thankfully, they went away.

It was six days of drifting before they spied a beach in the distance. All four of them paddled that way as furiously as they could, trying to overcome the current that threatened to carry them past the spit of land. But they made it. They were on land for the first time in over a week.

Later, a fishing boat came by and saw them jumping up and down on the sand, yelling for attention.

They were saved.

Kiyoshi suffered a high fever and was in a coma for a while. When he finally awoke, he was given rice and fish, but with it came a stern warning.

He was to tell no one what had happened. No one.

When he was well enough, he was sent back home, back to his brother and grandmother. But first, before he was even allowed to see them, he had to pay a visit to the police station. There, once again, he was ordered to remain silent about the sinking of his shipânot even telling his grandmother or older brother.

It was imperative that no one should ever learn what happened to the young passengers of the

Tsushima Maru

.

Tsushima Maru

.

Â

Â

Â

When, in 1944,

it was clear to them that the tide of the war had turned against them, the Japanese began to prepare for the long-anticipated invasion. The first step was to evacuate schoolchildren and their teachers out of major cities and key territories around the Pacific and place them in rural camps. Their motives were not totally humanitarian. They wanted to assure a supply of soldiers for the future of the empire once the invasion had been repulsed and the war had been won.

it was clear to them that the tide of the war had turned against them, the Japanese began to prepare for the long-anticipated invasion. The first step was to evacuate schoolchildren and their teachers out of major cities and key territories around the Pacific and place them in rural camps. Their motives were not totally humanitarian. They wanted to assure a supply of soldiers for the future of the empire once the invasion had been repulsed and the war had been won.

Over half a million children were successfully moved to those camps.

Eight hundred and twenty-six children were aboard the

Tsushima Maru

on the night of August 22, 1944. She was unmarked, not flying any flag or indicator that she was anything but a troop transport. She was un-lighted, too. Even Japanese cargo vessels typically had lights. The escort vessels around herâa destroyer and a gunboat, each undeniably a warshipâseemed to confirm that whatever cargo or personnel the ship carried, she was certainly a military target.

Tsushima Maru

on the night of August 22, 1944. She was unmarked, not flying any flag or indicator that she was anything but a troop transport. She was un-lighted, too. Even Japanese cargo vessels typically had lights. The escort vessels around herâa destroyer and a gunboat, each undeniably a warshipâseemed to confirm that whatever cargo or personnel the ship carried, she was certainly a military target.

That's what Captain John Corbus and the

Bowfin

crew assumed as well. There was no reason for anyone on the American submarine to believe otherwise.

Bowfin

crew assumed as well. There was no reason for anyone on the American submarine to believe otherwise.

Seven hundred and sixty-seven children died in the sinking. Only fifty-nine survived.

Those passengers of the

Tsushima Maru

who lived were forbidden to speak of the disaster under threats of severe punishment, both to them and their families. The Japanese simply could not afford for news of the tragedy to reach an already demoralized populace.

Tsushima Maru

who lived were forbidden to speak of the disaster under threats of severe punishment, both to them and their families. The Japanese simply could not afford for news of the tragedy to reach an already demoralized populace.

It was twenty years after the war before the truth of the

Bowfin

's target was ultimately known. Even now, more than sixty years later, little has been written outside Japan about the incident. Ironically, in Japan, where the tragedy was to be kept absolutely quiet, there have been several books published on the event, as well as documentary broadcasts. There has even been an animated feature movie produced dealing with the subject.

Bowfin

's target was ultimately known. Even now, more than sixty years later, little has been written outside Japan about the incident. Ironically, in Japan, where the tragedy was to be kept absolutely quiet, there have been several books published on the event, as well as documentary broadcasts. There has even been an animated feature movie produced dealing with the subject.

Memorial ceremonies are regularly held at sea near where the ship sank, and there are monuments for those lost at several cities from which the victims came.

None of the books, movies, or monuments blames America, John Corbus, or the

Bowfin

for the tragedy that occurred that night. They consider it to be but another example of the horrors of war.

Bowfin

for the tragedy that occurred that night. They consider it to be but another example of the horrors of war.

Â

Â

Â

The

Bowfin

came directly

to the East Coast after the war ended and began an on-again, off-again career as a reserve fleet boat, a pier-side trainer, and an auxiliary research submarine. She was decommissioned for the final time in December 1971 and her name was struck from the Naval Vessel Registry. Her service was done and she, like many of her sisters, was likely headed for the scrap heapâliterally.

Bowfin

came directly

to the East Coast after the war ended and began an on-again, off-again career as a reserve fleet boat, a pier-side trainer, and an auxiliary research submarine. She was decommissioned for the final time in December 1971 and her name was struck from the Naval Vessel Registry. Her service was done and she, like many of her sisters, was likely headed for the scrap heapâliterally.

But in 1978, the Pacific Fleet Memorial Association was chartered, and a year later made the

Bowfin

one of its first purchases. Admiral Bernard Clarey, a former commander of the Pacific Fleet, was instrumental in obtaining custody of the submarine for the memorial group. Admiral Clarey was a young lieutenant at the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor and was in Hawaii that fateful Sunday morning. He had just returned from patrol aboard the USS

Dolphin

(SS-169) and was enjoying breakfast with his wife and fifteen-month-old son when the attack began. He served aboard submarines throughout the war.

Bowfin

one of its first purchases. Admiral Bernard Clarey, a former commander of the Pacific Fleet, was instrumental in obtaining custody of the submarine for the memorial group. Admiral Clarey was a young lieutenant at the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor and was in Hawaii that fateful Sunday morning. He had just returned from patrol aboard the USS

Dolphin

(SS-169) and was enjoying breakfast with his wife and fifteen-month-old son when the attack began. He served aboard submarines throughout the war.

In 1980, the

Bowfin

was made ready for an ocean transit and then towed across the Pacific to be docked adjacent to the USS

Arizona

Memorial Visitor Center. The

Arizona

, of course, is the best-known victim of the attack on Pearl Harbor and still rests at the bottom of the harbor, an underwater tomb for many of her crew who perished that day. Her memorial is one of the most visited naval history sites on the planet.

Bowfin

was made ready for an ocean transit and then towed across the Pacific to be docked adjacent to the USS

Arizona

Memorial Visitor Center. The

Arizona

, of course, is the best-known victim of the attack on Pearl Harbor and still rests at the bottom of the harbor, an underwater tomb for many of her crew who perished that day. Her memorial is one of the most visited naval history sites on the planet.

A year after arriving at her new home near the battleship, the

Bowfin

was opened to the public as a museum ship.

Bowfin

was opened to the public as a museum ship.

The “Pearl Harbor Avenger” had returned to her unofficial hometown.

In 1986, the submarine was designated a National Historic Landmark by the U.S. Department of the Interior. The ten-thousand-square-foot museum has a large collection of submarine-related exhibits, including weapons systems, submarine models, battle flags, photographs, and more. That includes a Poseidon C-3 missile, the only one of its kind on display anywhere. The museum also holds a collection of more than fifty episodes of the television series

The Silent Service

, a program that told the true stories of the exploits of submarines in World War II. These and other submarine videos are screened in the facility's mini-theater.

The Silent Service

, a program that told the true stories of the exploits of submarines in World War II. These and other submarine videos are screened in the facility's mini-theater.

Visitors may rent a cassette player that gives a narrated audio description while they tour the submarine.

On the grounds is a special memorial to the fifty-two submarines and the more than thirty-five hundred submariners who were lost in World War II.

The USS

Arizona

Memorial nearby is maintained by the U.S. Park Service and paid for by taxpayers. On the other hand, the

Bowfin

and her museum is run by a nonprofit group, so, unlike at the

Arizona

Memorial, visitors are charged an admission.

Arizona

Memorial nearby is maintained by the U.S. Park Service and paid for by taxpayers. On the other hand, the

Bowfin

and her museum is run by a nonprofit group, so, unlike at the

Arizona

Memorial, visitors are charged an admission.

The boat is located right next to the Arizona Visitors' Center, a couple of miles off Highway H1. In addition to the USS

Arizona

Memorial, the battleship USS

Missouri

, aboard which the surrender by the Japanese took place, is also nearby.

Arizona

Memorial, the battleship USS

Missouri

, aboard which the surrender by the Japanese took place, is also nearby.

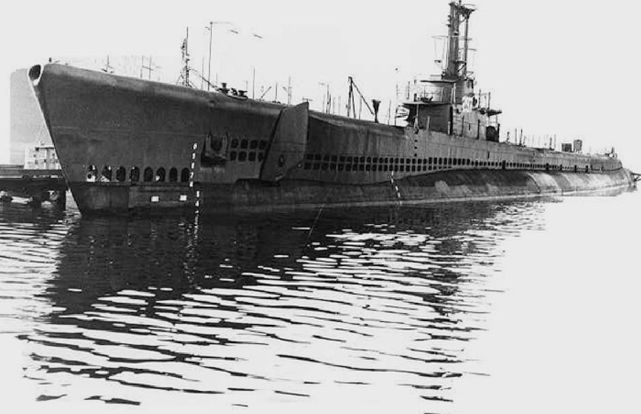

USS

LING

(SS-297)

LING

(SS-297)

Courtesy of the U.S. Navy

USS

LING

(SS-297)

LING

(SS-297)

Â

Class:

Balao

Balao

Launched:

August 15, 1943

August 15, 1943

Named for:

the ling fish, which is better known as the cobia. Near the end of the war, those responsible for naming vessels had almost run out of fish names and had resorted to using less accepted or regional names for fish that had already been used.

the ling fish, which is better known as the cobia. Near the end of the war, those responsible for naming vessels had almost run out of fish names and had resorted to using less accepted or regional names for fish that had already been used.

Where:

Cramp Shipbuilding Company, Philadelphia

Cramp Shipbuilding Company, Philadelphia

Sponsor:

Mrs. E. J. Foy, wife of the captain of the battleship USS

Oklahoma

(BB-37)

Mrs. E. J. Foy, wife of the captain of the battleship USS

Oklahoma

(BB-37)

Commissioned:

June 8, 1945

June 8, 1945

Â

Where is she today?

Claim to fame:

Though her keel was laid down in November 1942, the

Ling

did not sail for the Panama Canal and the Pacific until February 1946, after the war. Her brief activity in the Atlantic before the surrender of the Axis powers made her the last of the

Balao

-class submarines to operate in World War II.

Though her keel was laid down in November 1942, the

Ling

did not sail for the Panama Canal and the Pacific until February 1946, after the war. Her brief activity in the Atlantic before the surrender of the Axis powers made her the last of the

Balao

-class submarines to operate in World War II.

Other books

Guarded Heart by Jennifer Blake

Stepbrother: Impossible Love by Victoria Villeneuve

The Night of the Moonbow by Thomas Tryon

The Killin' Fields (Alexa's Travels Book 2) by Angela White

The Constant Heart by Dilly Court

Me and My Manny by MacAfee, M.A.

Ready to Love Again (Sweet Romance #2) by Keren Hughes

Perilous Travels (The Southern Continent Series Book 2) by Jeffrey Quyle

Dawn of Fear by Susan Cooper

Frozen Stiff by Sherry Shahan