Financial Shenanigans: How to Detect Accounting Gimmicks & Fraud in Financial Reports, 3rd Edition (9 page)

Authors: Howard Schilit,Jeremy Perler

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Accounting & Finance, #Nonfiction, #Reference, #Mathematics, #Management

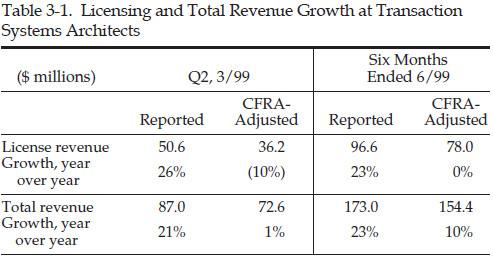

In March 1999, Transaction Systems Architects reported a misleading 26 percent jump in license revenue and a 21 percent increase in total revenue, as shown in Table 3-1. Virtually all of this impressive growth, however, came from the new and more aggressive revenue recognition approach, according to a CFRA report. Had investors realized that license revenue actually declined by 10 percent in March 1999, they probably would have considered selling their stock immediately.

Watch for Cash Flow from Operations That Begins to Lag Behind Net Income.

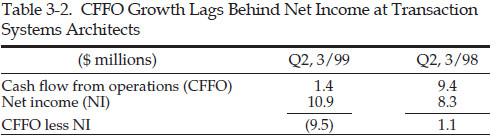

A red flag that should have alerted investors to take a closer look at Transaction Systems Architects’ revenue recognition was a trend in which the company’s cash flow from operations (CFFO) started to materially lag behind reported net income in the March 1999 quarter.

As shown in Table 3-2, CFFO trailed net income by $9.5 million in March 1999, whereas it exceeded net income in March 1998.

Warning of Premature Revenue Recognition:

Cash flow from operations materially lags behind net income.

Be Alert for a Jump in Unbilled Receivables.

A second warning sign for Transaction Systems Architects’ investors related to the sudden jump in accrued (unbilled) receivables. Under the company’s new accounting policy, revenue was recognized up front, yet customers paid much later. Unbilled receivables typically are not receivables at all. These accounts are generally created during the production period, when customers are not yet responsible for payment.

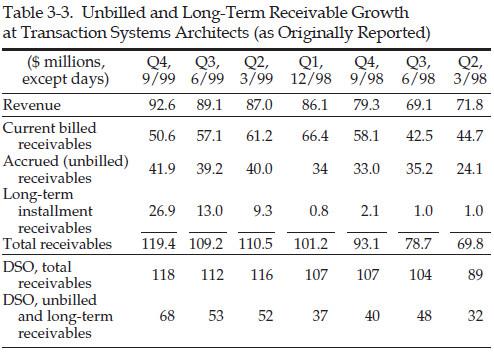

Notice in Table 3-3 that the company’s unbilled receivables increased from $24.1 million in March 1998 to $40 million in March 1999 (a startling increase of 65 percent), during a period in which sales increased just 22 percent (from $71.8 million to $87.0 million). This clearly suggests more aggressive revenue recognition.

Watch for Long-Term Receivables That Grow Faster Than Revenue.

A third and even bigger red flag was Transaction Systems Architects’ growth in long-term installment receivables. Normally receivables are collected within a month or two of a sale. Long-term receivables represent sales that the company will not collect

for more than a year after the Balance Sheet date

. In March 1999, long-term receivables jumped to $9.3 million from just $1.0 million a year earlier (and $0.8 million the previous quarter). By September 1999, long-term receivables ballooned to $26.9 million. The DSO calculation presented in Table 3-3 highlights the company’s accelerated revenue recognition. Total DSO increased from 89 days in March 1998 to 116 in March 1999. DSO on unbilled and long-term receivables jumped from to 32 to 52 days over the same time frame, and surged to 68 days by September 1999.

You Have to Pay the Piper Eventually.

By accelerating future-period sales into an earlier period, Transaction Systems Architects successfully plugged its short-term revenue shortfall while creating enormous problems for the future. By recognizing virtually all of the revenue from the entire five-year contract up front, the company created two major problems for itself. First, because legitimate future-period revenue had been shifted to the present period, it would no longer be available in the future periods. Second, achieving comparable revenue growth in the future on top of the inflated sales figure would be an enormous challenge.

Management Discretion on Long-Term Contracts May Accelerate Revenue

The previous examples demonstrated how Computer Associates and Transaction Systems Architects boosted revenue and profits by aggressively recording revenue on multiyear contracts up front. Certain types of long-term contracts, however, actually allow the seller to recognize some revenue even though future services remain to be provided. While these arrangements are guided by accounting methodologies permissible by generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), the timing of revenue recognition is very sensitive to discretionary management estimates.

In this section we discuss several of these arrangements and provide advice on how to spot instances in which management might be using overly aggressive estimates. Specifically, we cover

(1)

long-term construction contracts that use percentage-of-completion accounting

(2)

lease agreements

(3)

arrangements with several distinct deliverables

(4)

utility contracts recorded using mark-to-market accounting

Recording Revenue on Long-Term Construction Contracts Using Percentage-of-Completion Accounting

Revenue from long-term construction or production contracts (e.g., building a power plant) can be recognized over the production period under an accounting rule known as

percentage-of-completion

. The amount of revenue recognized under percentage-of-completion accounting is subject to various estimates, and as a result, this accounting methodology creates opportunities for financial shenanigans.

Look Out for Companies Inappropriately Using Percentage-of-Completion Accounting to Accelerate Revenue.

Service companies typically are ineligible to use percentage-of-completion accounting, since their projects have a shorter term. In addition, companies that sell products with very short production cycles should refrain from using percentage-of-completion.

Be Alert for Companies Using Aggressive Assumptions in Applying Percentage-of-Completion Accounting

. When using percentage-of-completion accounting, management calculates revenue based on the

percentage

of the project that was

completed

during that period. For example, assume that on a $1,500,000 contract, management estimates that total costs will be $1,000,000, and that $200,000 of costs were incurred during the first quarter. As shown in the accompanying accounting capsule, percentage-of-completion accounting would dictate that 20 percent of the revenue be recorded in the first quarter (even if a different amount would be billed to the customer). This methodology relies on a number of estimates, and as a result, management can make aggressive assumptions. For example, if management simply assumed that total estimated costs would be $800,000 (instead of $1 million), revenue in the first quarter would be 25 percent of the total contract value (instead of 20 percent). A warning sign for investors that a company has been using percentage-of-completion accounting improperly would be a large increase in unbilled receivables when sales and billed receivables grow more moderately.

Accounting Capsule: Percentage-of-Completion Accounting

Percentage-of-completion accounting is typically used for long-term construction or production contracts. Under percentage-of-completion accounting, the amount of revenue recognized in a given period is determined by the

percentage

of the total contract that was

completed

during the period. To calculate revenue, companies first determine the amount of costs they incurred under the contract as a percentage of the estimated total costs to be incurred over the entire life of the contract. Then, this percentage is applied to the total revenue expected to be recognized under the contract, as illustrated here.

Even when it is appropriate for companies to use percentage-of-completion accounting, incorrect estimates and bad luck can lead to inflated revenue and earnings. That’s what happened at defense contractor Raytheon Company. Raytheon recorded revenue for several years based on estimates of costs and expected unit sales. When it became clear that the revenue from the contract would materially lag behind the original estimates, Raytheon announced that the previously reported revenue was too high, and it was forced to take a one-time charge.

Potential Problems in Using Percentage-of-Completion Accounting

• Companies may use percentage-of-completion accounting when it is not appropriate.

• Companies may make aggressive assumptions to accelerate revenue.

• Revenues may be inflated simply because honest estimates are off the mark.

Recording Revenue from Assets Leased to Customers

Lease accounting is another topic that, like percentage-of-completion accounting, relies heavily on management’s estimates. Investors must monitor these inputs, since management might begin using unreasonably optimistic projections. In the case of Xerox Corporation, management inflated revenue and earnings by billions of dollars using lease accounting tricks, some of which are discussed in this section. When the shenanigans finally caught up with Xerox, the company restated equipment revenue by $6.4 billion and pretax earnings by $1.4 billion.

Accounting Capsule: Capital Leases

Certain equipment leases should be treated in a fashion similar to the treatment for an outright sale. These are called

capital leases

. At the inception of the lease, the seller (called a lessor) recognizes as revenue a large portion of the present value of future lease payments. Estimates such as the discount rate, residual value, length of the contract, and other lease terms dictate the timing of revenue recognition over the course of the lease.

For example, the discount rate is used to calculate the current value of future lease payments, adjusted for the time value of money. This present value is recognized as revenue immediately, and the remainder of the payments is recorded as interest income over the lease term. A higher discount rate yields a lower present value for revenue recorded, while a lower discount rate yields a higher present value. By choosing an inappropriately low discount rate, management could aggressively accelerate the recognition of revenue.