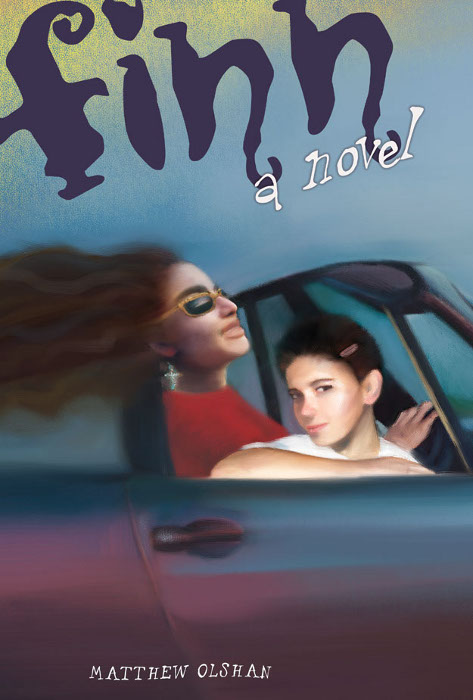

Finn

Authors: Matthew Olshan

Copyright ©2001 by Matthew Olshan

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote passages in a review.

Published by Bancroft Press

P.O. Box 65360, Baltimore, MD 21209

800.637.7377

www.bancroftpress.com

Cover design and illustration by Steven Parke, What? Design, www.what-design.com

Book design by Theresa Williams, [email protected]

Library of Congress Card Number: 2001086370

ISBN 1-890862-13-4 (cloth)

ISBN 1-890862-14-2 (paper)

Printed in the United States of America

Second Edition

for shana

Additional Praise for Finn: A Novel

“A

ngry angry angry,

is what you are,” they tell me, but I think I’m less angry than quiet, the kind of quiet that makes people nervous because they can’t tell what you’re thinking, and most of them assume the worst. I do get angry sometimes, but who doesn’t? There’s strength in anger, which goes against what school counselors will tell you.

Since I’ve been living with my grandparents, I’m a lot less angry, but I’m still pretty quiet. My grandparents go on and on about how lovely I am—which I’m not—and how bright—which I’m definitely not. They give me an allowance, which is something new, and nice clothes. Sometimes, when they’re showing me off to their wrinkly friends, I feel like saying, “She pees when you give her a bottle!” like those talking dolls they gave me when I first came to live with them, before they understood I was way past dolls.

Still, I like how quiet their house is. I like that there are always clean sheets, even if they do smell like mothballs. Everything in my grandparents’ house smells like mothballs, even them sometimes, but it’s not a terrible smell. At least it smells like someone’s trying. And there are times, late at night, when the smell of the mothballs and the clean sheets and the glow of the stupid little nightlight they insist I need and the cicadas singing outside—when all of it together makes me feel like I’m in a cocoon, like I could become something very nice.

I’ll fall asleep with those thoughts sometimes, and even if I haven’t had the nightmares, in the morning I’ll be lashed down by the sheets. It’s the way my grandmother tucks them in. They twist around your ankles like ropes. Come morning, I’ll try to hide the fact that I’m in one of my moods, but by now my grandparents know better. When I plop down at the kitchen table, they’ll give each other the look that says, “Watch out.” They won’t bother being cheerful. My grandfather will say, “Another bad night.” He’s right just to say it and not to ask it, because those mornings, I can barely keep my eyes open, much less answer questions.

They used to try to force me to talk about “it,” whatever “it” was. But forcing someone to talk is like forcing them to eat: you may have to break their jaw to do it, and the whole thing can land you in a hospital.

They’ve been sending me to a girls school called Field, which is supposed to be different from other schools in that you go on a lot of field trips. At first, I liked it. The teachers weren’t always making me empty my pockets, and I could go to the bathroom without an act of Congress. My main teacher, Ms. Bellows, was extra nice to me, and not in a condescending way. She was the only one who bothered to call me “Chlo,” the way I like, and not “Chloe,” with two syllables and the ugly “ee” sound at the end, which is my actual name. The rest of the teachers insisted on the whole ugly thing.

Ms. Bellows understood the kind of nice that being nice is supposed to be about. Most of the other teachers practiced the kind of nice where you’ve heard a lot of bad stories about someone and think you have to be their “special buddy.”

One of the teachers at Field, Mr. Lynch, tried way too hard to be my special buddy, always coming up to me, even when I was with a crowd. It was completely inappropriate. He’d say things like, “Hey, girlfriend!” or “Like those shoes!” It’s not impossible that my shoes were nice, or that Mr. Lynch could have genuinely liked them, but the time to compliment them is definitely not when I’m trying to make new friends. Nothing scares away potential friends like a teacher who’s complimenting you all the time. It’s suspicious.

Mr. Lynch was getting out of hand, so I decided to do something about it. A golden opportunity came one day when he was showing me pictures of his family—that’s how much he wanted me to feel like his special pal!—and I saw that his wife was Mexican and very young. She was okay-looking, in that stubby way. You know: too much make-up, not a lot of neck. I don’t have anything against Mexicans in general, although a lot of people around here do, but I wanted to get Mr. Lynch off my back, so I started making some seemingly harmless comments about his wife. Such as: wasn’t she exotic looking, how long had they been married, etc. Mr. Lynch said that he and Mrs. Lynch were practically newlyweds in that they were about to celebrate their second anniversary.

As soon as I heard that, I had my in. Mr. Lynch is not what you would call a young man, although the fact that he’s fat makes his face look pretty young. Unless I’m utterly wrong, he’s forty. A man his age should have been celebrating at least his tenth anniversary, if not more.

I congratulated him anyway. I told him I thought that two years of marriage was a

fan-tas

-tic achievement. It wasn’t hard to lie to him. Mr. Lynch is the kind of person who sops up compliments, probably because he doesn’t feel he really deserves them.

Then, when I was sure he was feeling like my special buddy, I told him—not in a mean way, just as a sort of casual observation—that I was surprised Mrs. Lynch hadn’t divorced him yet. Mr. Lynch was a little shocked by that. He asked me why I would say such a thing. I said it was common knowledge that Mexican women married American men to become citizens, and then divorced them later because they find American men fat and not very accomplished lovers.