Firebirds Soaring (12 page)

Authors: Sharyn November

I can’t explain. I don’t even know how it got into the cubby. “It was sort of a present,” I say after a minute. I’m not sure I want it.

“Who—? Well, never mind. I hope you thanked them.” My mother slips it under my rest rug, then puts the box into the back of the station wagon. I can feel it through the back of my neck as we drive.

She pulls into the parking lot of Ackerman’s Drugs, six blocks from our house. “I need to pick up a few things,” she says. “So I thought we might celebrate with a sundae, Miss First Grader.”

Ackerman’s smells like perfume and ice cream mixed with bitter medicine dust. The candy counter is next to the red-and-chrome soda fountain. While my mother buys aspirin and Prell shampoo, I look at every candy bar in the display. No lightning bolts. “Do you have a Raxar? ” I ask the counterman when he is done making a milkshake.

“Raxar?” He wrinkles his forehead. “Never heard of it.”

I’m not really surprised.

When we pull into the driveway, there are police cars parked two doors down. My mother frowns and carries my box to my room before she walks down to the Galloways’ to see what’s happened.

I put the record on my dresser, next to the box with the nickel.

That night my mother checks the lock on the front door twice after dinner. At bedtime, she tucks me in tight and kisses me more than usual.

“Can I have a record player for my birthday?” I ask.

She smiles. “I suppose so. You’re a big girl now.”

So you are,

echoes Hollis in his odd, sad voice.

So you are.

echoes Hollis in his odd, sad voice.

So you are.

“I am,” I say. “First grade.”

“I know, honey.” My mother sits down on the edge of my covers. “But even big girls can—” Her hand smoothes the unwrinkled sheet, over and over. “When you were out playing, did you ever see your friend Jamie talking to a man you didn’t know?”

I think, for just a second, then shake my head and keep my promise.

“Well, you be careful.” She strokes my cheek. “Don’t go anywhere with a stranger, even if he gives you candy, okay? ”

“I won’t,” I say. I don’t look at the record on my dresser, and wonder if I’m lying.

ELLEN KLAGES

was born in Ohio and now lives in San Francisco.

was born in Ohio and now lives in San Francisco.

Her story “Basement Magic” won the Nebula Award in 2005. Several of her other stories have been on the final ballot for the Nebula and Hugo awards, and have been translated into Czech, French, German, Hungarian, Japanese, and Swedish. A collection of her short fiction,

Portable Childhoods

, was published in 2007.

Portable Childhoods

, was published in 2007.

Her first novel,

The Green Glass Sea

, won the Scott O’Dell Award for historical fiction and the New Mexico State Book Award. It was a finalist for the Northern California Book Award, the Quills Award, and the

Locus

Award. A sequel,

White Sands, Red Menace

, has recently been published.

The Green Glass Sea

, won the Scott O’Dell Award for historical fiction and the New Mexico State Book Award. It was a finalist for the Northern California Book Award, the Quills Award, and the

Locus

Award. A sequel,

White Sands, Red Menace

, has recently been published.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

This story came out of my oldest, strongest memory.

I’m in bed, in the yellow bedroom of my parents’ house. (I moved out of that room when my sister Mary was born, when I was three and a half, so I’m younger than that.) It’s dark, and I’m listening to a Disney record narrated by Sterling Holloway, the story of a little taxi, sad and desperate, set in a seedy, Damon Runyon city. A Will Eisner city.

The Naked City

.

The Naked City

.

Vivid, inexplicable images, outside the realm of any possible nursery-school-age experience: a tangle of concrete struts arching over alleys, soot-stained brick, corrugated metal garbage cans, neon over a distant doorway, jazz filtering out. And it is always bound to that yellow bedroom, which is as accurate as carbon dating in my family.

All my life those images sat in the back of my mind, dimly lit and seductively creepy. Where did they come from? I’d occasionally ask someone my age if they remembered a Disney record called

The Depressed Little Taxi.

Ha. No. At flea markets, antique sales—and much later, on eBay—anywhere there was an accumulation of late 1950s children’s records, I thought—

What if?

—and looked. I never found a trace of its existence.

The Depressed Little Taxi.

Ha. No. At flea markets, antique sales—and much later, on eBay—anywhere there was an accumulation of late 1950s children’s records, I thought—

What if?

—and looked. I never found a trace of its existence.

Then one night last fall, in the wee hours, I was playing on my laptop, a glass of wine at hand, tired, but not quite ready to sleep, following odd links to other odd links. I typed “Sterling Holloway” into Google’s search bar; it is his voice that is most evocative, that instantly conjures my preschool room, shadowed with loss and regret.

I went from site to site to site to site and at two in the morning, on YouTube, I may have found it. A cartoon, not a record, but if it

was

the source, it would permanently overwrite the elusive images that had lived, for fifty years, on the borders of fantasy, dream, and memory, and I would lose—forever—that sense of noirish magic.

was

the source, it would permanently overwrite the elusive images that had lived, for fifty years, on the borders of fantasy, dream, and memory, and I would lose—forever—that sense of noirish magic.

I had to watch it. I had to find out.

But I had to write this story first.

Louise Marley

EGG MAGIC

T

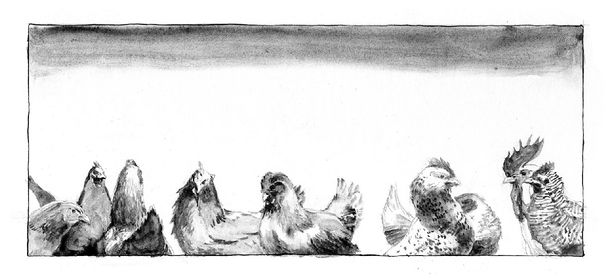

ory lingered in the chicken pen in the September sunshine, watching her flock scratch through the grass, spreading their feathers in the morning breeze. The banty, Pansy, trotted to Tory to have her glossy black and red feathers stroked. She chirkled under Tory’s fingers. “Silly Pansy,” Tory said. “You act more like a puppy than a chicken.”

ory lingered in the chicken pen in the September sunshine, watching her flock scratch through the grass, spreading their feathers in the morning breeze. The banty, Pansy, trotted to Tory to have her glossy black and red feathers stroked. She chirkled under Tory’s fingers. “Silly Pansy,” Tory said. “You act more like a puppy than a chicken.”

Most people, she knew, thought chickens were dumb. The kids at school, except for the 4-H Club, thought her hens were stupid, smelly animals who didn’t care a bit about people. Tory knew better. Pansy loved to be petted, to be scratched right at the back of her short neck. The stately leghorns followed at her heels when she filled the feed dispensers, when she poured out the scratch or corn or scattered the grit. The pair of Black Jersey Giants pecked around her toes as she filled the water dispenser, hoping for the kitchen scraps she brought out in plastic bags. The Barred Rock layers waited for Tory to come through the gate every morning, and then dashed ahead of her into the coop, making a game of pretending to protect their eggs. Her single Araucana, tufted head looking as if someone had stuffed her ears with cotton, preened beside her nest each day, making certain Tory knew who had laid those azure eggs.

Only Rainbow kept a haughty distance, patrolling the far side of the pen.

The school bus rumbled around the corner and turned into their lane. The boys, five-year-old twins and twelve-year-old Ethan, boiled out of the house and down the gravel drive to the bus stop. Rosalie, Tory’s stepmother, stood on the porch steps, calling her name.

“Rainbow!” Tory said. “Come say good-bye. I have to go to school.”

The hen turned one black eye in Tory’s direction. She gave a single sharp cluck, a sound that would have been a snort in another kind of animal. The banty chirruped. Tory murmured, “Never mind, Pansy. Rainbow’s just cranky. It’s because she’s so much older.”

Not even Henry, Tory’s father, knew how old Rainbow was. She was older than any of the other chickens. Pansy might live ten years if she were lucky, if she didn’t get sick or get nabbed by the boys’ border collie. But Rainbow, tall, thin, and long necked, had been left behind by Tory’s mother when she left. That had been sixteen years before.

Rainbow’s plumage changed colors with the seasons, from gold and black, to green and black, to rusty brown and black. She fit no breed or crossbreed Tory could find in any catalog, and she mirrored Tory’s own mysterious heredity—her sharp black eyes, her long neck, her narrow hands and feet. Tory looked nothing like her father, who was big and sandy haired. Tory had a faint memory of her mother, an ephemeral impression of a thin face, long fingers, lank black hair. Henry had spoken to Tory of her mother only once. A gypsy, he said. A traveler. He would not say how they had met, or why she had left.

“Victoria! Hurry, you’ll miss the bus!” Rosalie waved to her. She was wearing that awful old apron again, pink, with a bedraggled ruffle around the bottom. Her round face was pink, too, and her hair, an indeterminate brown, stuck up in every direction.

Victoria gathered up her egg basket and her backpack and let herself out of the pen.

Rosalie called again, “Victoria! Give me your basket and run!”

Tory didn’t run, but she did hurry across the yard to hand over the egg basket.

“Don’t forget your 4-H meeting, dear.”

Tory rolled her eyes as she turned toward the bus. Rosalie tried too hard. If she were only thin and mean, she would be the perfect wicked stepmother from the fairy tales, but Rosalie went overboard in the other direction, watching over everything, interfering in everything. She had bought Tory’s first bra for her before she asked for one. She fussed over Tory’s hair, suggesting awful hairstyles, and she nagged at her to wear colors other than black. She made her clean her fingernails every day when she came in from the chicken coop, and she constantly reminded her of things she already knew, like her 4-H meetings. Tory wished she would just devote herself to the boys and let Tory take care of herself.

The boys were already in the bus when Tory climbed up the ribbed rubber steps. The bus lurched forward the moment the doors closed, and she grabbed seat backs as she worked her way to her usual seat. Three seats back from the driver. Not too far forward, which would be weird. Not too far back, where her half brothers could torment her. She sank onto the bench seat, her backpack under her feet

,

the

Catalog of Contemporary Poultry

on her lap.

,

the

Catalog of Contemporary Poultry

on her lap.

Newport was a small town, and the bus carried little kids as well as high school students. Ethan and Jack and Peter sat in the back. The older ones sidled between the seats in twos and threes, sitting together, giggling and talking. Tory always sat alone.

Alison Blakely climbed on the bus, flipping her long blond hair with her fingers as she came up the steps. She looked like the classic fairy-tale princess, but she had a sharp tongue. She grinned pointedly at Tory’s catalog. “Not more chickens?”

Tory kept her eyes down, but her cheeks warmed. She shook her head.

Josh Hudson was waiting for Alison. He scooted over to make room for her, and she leaned close to whisper something in his ear. He laughed, and Tory glanced over her shoulder. The prince and princess, fair and beautiful. Tory looked away from them. She was nothing like them, she reminded herself. She was dark and dangerous. Solitary. A mysterious and magical future awaited her when her mother returned. Her mother, the gypsy queen.

“Hey, Tory,” Josh called.

Tory pushed ragged black strands away from her forehead. “What? ”

“One of the eggs you brought us last week was really weird,” Josh said, more loudly than necessary. “It was blue!”

Alison made a face. “Ooh, blue eggs. Ick! I’m glad we get ours at the store.”

Tory bridled. “He means the shell, Alison. The shell is blue, not the egg!”

Alison shivered. “Still!” she cried.

Tory glowered, and her cheeks burned. “I have an Araucana hen. She’s very rare, and she lays blue eggs. And all my eggs are better than the ones from the store!” She was embarrassed at the tension in her voice, and she wrenched herself back to face forward again.

Alison wasn’t being fair. Tory’s hens laid eggs in a palette of colors—white, tan, speckled, and blue—but they all had beautiful dark yellow yolks and a full, rich taste. Her flock ran free in their pen, in fresh air and sunshine. They ate a good laying mash and drank water from a scrupulously clean tank.

Tory knew what eggs from the store looked like, with their pallid yolks and runny whites. She wished she had said that. She should have shivered, like Alison, as if the very thought of eggs from chickens who never saw the sky made

her

feel sick. But it was too late now.

her

feel sick. But it was too late now.

She tried to focus on

Contemporary Poultry

as the bus rattled along.

Contemporary Poultry

as the bus rattled along.

She was surprised to see Charlie Williams jump up into the bus. Usually he drove his father’s pickup to school. His long legs took all three steps at once, and he grinned at her as he came down the aisle. Charlie was tall and thin, even thinner than Tory. His knobby wrists stuck out of his shirt sleeves, and his sneakers seemed enormous. “Hi, Tory.”

She nodded to him awkwardly and murmured, “Hi.”

He stopped beside her seat. “My mother says she hopes you have lots of eggs this week. She’s baking for Christmas already.”

Tory lifted her face to see his eyes. They were a nice clear brown, not the glittery black of her own. And Rainbow’s. “There should be plenty. All my hens are laying well.”

“That’s great.” Charlie nodded. “I’ll tell her.”

“How many does she want?”

“She said she’d call your mom when she knows.”

Tory stiffened. “Rosalie’s not my mom, Charlie.”

“Well—yeah.” His thin face reddened. “I know. I just meant . . .” He dropped his eyes. “Sorry.” He shifted his backpack and stumbled a little as he worked his way back to his seat.

Other books

Access All Areas by Severin, Alice

Placebo Junkies by J.C. Carleson

A Member of the Council by Lynn Cahoon

The Underdogs by Mike Lupica

Bride On The Run (Historical Romance) by Elizabeth Lane

The Lie by Linda Sole

The Glory Hand by Paul, Sharon Boorstin

Disney by Rees Quinn

Fade to Black - Proof by Jeffrey Wilson

Heir of Stone (The Cloudmages #3) by S. L. Farrell