Flapper (27 page)

Authors: Joshua Zeitz

In the remote mountain towns of Kentucky, farm and mine families clipped ads from mail-order catalogs and magazines, mounted

them to the wall with a mixture of red pepper, rat poison, and flour-and-water paste (to keep the mice from gnawing at the paper), and coated them with a combination of sweet anise roots and arrowroot to leave a friendlier aroma.

20

Color pictures of new food brands adorned the walls of their country kitchens; ads featuring new toys formed a backdrop in children’s bedrooms; images of premade furniture and glass and porcelain finery decorated living rooms.

In 1905, a social worker surveyed working-class tenement homes in downtown Manhattan and found that most contained cheap chromos—either reproductions of paintings or consumer ads—on the walls.

The hunger of ordinary people for new pictures and colors held out part of the answer to the plague of underconsumption. Color, wrote Artemas Ward, an advertising industry pioneer, is a “priceless ingredient.

21

… It creates desire for the good displayed.… It imprints on the buying memory. [It] speaks the universal picture language” and touches “foreigners, children, people in every station of life who can see or read at all.” A billboard promoter summed up the point best. “It is hard to get mental activity with cold type,” he said, but “YOU FEEL A PICTURE.”

And pictures were there for the gazing. Between 1918 and 1920, the volume of annual consumer advertising doubled to an astounding $2.9 billion (equal to nearly $20 billion in today’s money).

22

Most of these new appeals were concentrated in magazines, which shifted in the 1880s and 1890s away from the old business model of high prices and low circulation toward a more profitable system of low newsstand and subscription rates and high circulation. Under the new arrangement, magazines turned most of their profits from advertising revenues rather than direct sales.

Aided by the nation’s extensive railroad system, the introduction of cheaper, second-class postal rates in 1879 and rural free delivery in 1896, and new technological advances like the rotary press, magazine circulation in the United States jumped to a whopping two hundred million in 1929, or 1.6 magazines per person, per month.

23

By the time Scott Fitzgerald was writing for

The Saturday Evening Post

, his stories were reaching over a quarter of all households in cities like

Seattle, Washington. Other titles like

Good Housekeeping

and

Collier’s

enjoyed similar appeal in places as far-flung as Omaha, Nebraska, and Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Though magazines remained a distinct trapping of the middle classes, the expansion of the magazine market created the first truly national institution combining both news and entertainment. In turn, this vital institution created a market for national branding and advertising where none had existed before.

Among the highest-circulation magazines were several that catered specifically to women:

Good Housekeeping, Women’s Home Companion

, and

Ladies’ Home Journal

, which concentrated principally on homemaking topics, and

McCall’s, Delineator

, and

Pictorial Review

, which dedicated themselves increasingly to fashion and criticism. Other important women’s magazines like

Vogue

and

Harper’s Bazaar

had smaller circulations but exerted a disproportionate influence by virtue of their elite readership.

All told, between 1890 and 1916 a handful of women’s publications attracted more than one-third of all magazine ad revenues, reflecting the commonly held (but never substantiated) belief that women accounted for the lion’s share of all consumer purchases.

24

This meant that advertisers tailored many of their appeals to women, who were thought to be responsible for household purchases of soap, cleaners, canned foods, furniture, toiletries, and clothing.

To coax women into this new world of getting and spending—to convince them of the need to purchase more goods for themselves and their families—advertisers introduced startling new ideas about body image and fashion. In so doing, they created a visual ideal of the flapper that many women would find difficult to achieve.

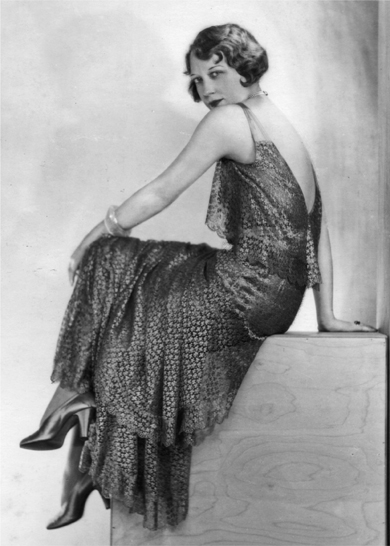

Fashion artist Gordon Conway, 1921, introduced millions of magazine readers in Europe and America to the visual style of the New Woman.

18

10,000,000 F

EMMES

F

ATALES

“H

APPY DREAMS AND

illusions”—that’s what magazine advertisements and illustrations offered to American women, or so said Frank Crowninshield, the legendary editor of

Vanity Fair.

“Such pages spell romance to them,” he observed. “They are magic carpets on which they ride out to love, the secret gardens into which they wander in order to escape the workaday world and their well-meaning husbands … after a single hour’s reading of the advertising pages, 10,000,000 housewives, salesgirls, telephone operators, typists, and factory workers see themselves daily as

femmes fatales

, as Cleopatra, as Helen of Troy.”

1

In the pages of the slick new consumer magazines lay the images that American women increasingly aspired to imitate, and by the 1920s, arbiters of culture like Frank Crowninshield enjoyed considerable influence in crafting popular tastes and styles. Illustrated magazine covers depicting sleek, angular women with skirts flapping in the wind, legs bared to the elements, and elegant garments falling naturally along their silhouettes dictated the image of the modern woman no less than the glossy advertisements nestled inside the front and back pages.

One of Crowninshield’s star cover artists, Gordon Conway, wielded more influence than most. No fewer than 110 fashion houses—including all of the leading Parisian couture shops—invited

her to sketch their work. Department stores commissioned her for print advertisements. Broadway directors hired her to design sets and costumes. Filmmakers in London and Paris turned to her expertise when they outfitted their silent screen actresses. Though few people outside the art and publishing worlds knew her name, anyone who subscribed to

Harper’s Bazaar, Women’s Home Companion, Vogue, Vanity Fair, Judge, Town & Country, Metropolitan, Country Life—

virtually every major fashion magazine of the era—knew her work. Anyone who saw a European film or took in a local production of a London or Broadway play saw her style.

Conway’s flapper was slender, sleek, and brilliantly aloof. Her clothes were rendered with tremendous precision, yet her facial expressions and features were often distant and even obscure. For Conway, the New Woman’s grace and being came from her willowy outline and modern attire.

Born in 1894 to John Conway, a prominent lumberyard owner, and Tommie Conway, his world-wise wife, Gordon spent the first years of an unusually privileged childhood roaming the grounds of her family’s handsome Queen Victoria frame house in Cleburne, Texas. Marked out from all the other neighborhood homes by its distinctive, fish-scale shingle facade and the rows of books and paintings that adorned its interior, the Conway residence bespoke the family’s unparalleled position in the community.

From an early age, Gordon was treated like a little lady—not a little girl. Her parents were local apostles of high culture and considered it de rigueur that their daughter attend the numerous dance and orchestra performances they sponsored in their home. Gordon grew up on chamber music, poetry recitals, and salons staged on the long porch that wrapped around the Cleburne house, bounded on one side by a hand-carved balustrade.

When Gordon was nine years old, her family—enjoying still greater prosperity from John’s lumber business—moved to a stately new mansion in Dallas, right on the corner of Ross and Harwood, a neighborhood known locally as “Silk Stocking Row” and the “Fifth Avenue of Dallas.”

Dallas was a boomtown in those days, and Gordon was lucky to be among the “so-called 400,” the leading families who mattered most in the insular but wealthy community of Texas oil barons and lumber tycoons. There, in the blazing southwestern heat, the four hundred raised faux Gothic mansions and French châteaus, they lined their newly paved streets with tall trees from exotic places and paid one another visits in custom-made, horse-drawn carriages, each driven by a uniformed coachman.

As the daughter of wealthy socialite parents, Gordon enjoyed a host of opportunities that equipped her with the sense of cosmopolitan style that would serve her well in her later career. Even after her father died young and unexpectedly in 1906, Gordon enjoyed a level of refinement and comfort unknown to most Americans of their era. Raised on a steady diet of opera, ballet, modern dance, classic and modern poetry, and symphony music, Gordon honed her already refined sensibilities as a student at the National Cathedral School in Washington, D.C., where she studied piano, elocution, and dance and learned to speak Italian, Spanish, and French with relative ease, if not fluency. Tall, dark haired, and remarkably poised, Gordon was, according to her childhood friend Margaret Page Elliott, “as graceful as a fawn.

2

She was not a beauty like her mother in a classic way, but she could just toss an old shawl around her shoulders and look as glamorous as all get-out. If the rest of us tried that we’d look like rough-dried laundry hanging on a clothesline.”

Gordon’s rigorous training in the arts and languages paid handsome dividends when, in August 1912, she and her mother sailed for Europe to spend the better part of two years traveling, studying, and meeting the men and women who were ushering in a modernist revolution in Western art and literature. In Munich, she gained extensive exposure to the work of continental futurists and cubists. “Ridiculous!” she wrote in her diary in response to the various works by Pablo Picasso and other leading innovators, though she would later help popularize these artistic conventions by incorporating them in her advertising and cover art.

Gordon and Tommie spent their two-year sojourn deeply enmeshed

in European culture—both high and popular. They became well-known American customers at the leading Parisian couture houses, roughly around the time Coco Chanel was launching her signature line, and they frequented tea parties, dances, and recitals with leading members of the American expatriate community.

But the fun couldn’t last forever. As the clouds of war gathered in the summer of 1914, Tommie and Gordon found themselves on a mad dash from the Alps, where they had been hiking through the Maloja Pass. They somehow managed to talk themselves onto the last train bound for Zurich and then plodded their way onward to Lausanne, where Gordon sporadically attended school.

As German soldiers broke through Belgium and headed west toward France, Gordon, holed up in her bedroom suite at the Hotel Royal, recorded her thoughts amid the steady clatter of heavy rain.

3

“I am very sad on account of the war,” she began, “for Germany is fighting and Renee”—a friend, perhaps a suitor—“is there … there is a revolution in Paris and Anibal”—another beau?—“is there. Silvio”—yet another smitten friend—“is stuck in France.” Gordon pondered the fate of all the smartly dressed men who had courted her in Rome just a few months before and worried that the war would consume all of her “bounty of beaus.”

In the days before their departure for America, Gordon and Tommie watched with great emotion as ten thousand Swiss soldiers swore an allegiance to God and country and marched off into the great unknown. Mother and daughter then managed to catch the last, overcrowded train from Geneva to Paris. Packed like sardines into ordinary coach cars, they endured a nineteen-hour journey and had to negotiate their way around vast crowds at the Gare de l’Est. “Paris has changed!” Gordon wrote in her diary. “There’s no one on the streets and lights are not burning.”

Though the German army was fast moving west, Tommie and Gordon found time for one last whirlwind shopping expedition at the houses of Worth, Poiret, and Patou. They then caught a ferry to England, wound their way up by train to Liverpool, and boarded the RMS

Olympic

for a safe return to New York. For now, their European adventure had drawn to a close.

Though she claimed no formal training as an artist, back in the United States, Gordon’s vast knowledge of continental painting, steady hand at the drawing board, and—perhaps most important—extensive network of well-placed friends and acquaintances soon drew her to the attention of Heyworth Campbell, art director for Condé Nast’s various high-end publications, including

Vanity Fair

and

Vogue.

Headquartered in a stylish office suite (Mrs. Nast herself chose the decor—an art deco interior very much in line with new trends in architecture and design), Campbell and his boss, Frank Crowninshield, drew on the talents of a wide circle of friends, including Dorothy Rothschild (later, Dorothy Parker), who had not yet become a leading light of the Algonquin Round Table, and Ted Shawn and Ruth St. Denis, the celebrated husband-and-wife team whose company, Denishawn, pioneered modern dance in America.