Flash and Filigree (22 page)

Neither spoke for a long while, and then they were parked on a thick-wooded hill overlooking the sea.

With the top down, it was a beautiful spring night; a full-rounded moon, all golden pink, lay low against the endless blue water like a great dripping orange.

“Does the moon look flat to you, or round?” asked Ralph.

“I don’t know,” said the girl sadly, looking at the moon.

He took her hand, and there were only the sounds of the tide-swept shore below, and the wind.

“Do you . . . do you love me?” he asked with a soft finality, as though these might somehow be his very last words.

All around them steeped the lazy depth of grass that strove gently toward shades of cobalt near the earth, unthreatened now and forever by a moon made soft through the light night-driven clouds and, seemingly too, by a wind that stirred the jacaranda above with a motion and sound no less languid than the caressing breath of the girl.

“Why, how do you mean?” she asked, seemingly really ingenuous.

It was almost midnight and, everywhere now, small night-birds were beginning to flutter and, finally, to sing.

“The way . . . I love you,” said the boy.

And the birds sang, softly, and in a way, too, that did seem to promise they would sing right on through forever, dawn after dawn.

D

R.

E

ICHNER

L

AY

in his own big bed, in the total darkness of his room, fully awake. On the night-table and scattered over the counterpane were about seventeen magazines.

The Doctor had retired at nine and had read for a while before turning out his lamp. He had fallen asleep straight away and had slept soundly for several hours, only to wake up suddenly, long before scheduled.

For five minutes he lay quite still, peering up into the darkness. Then he threw back one half of the top part of his counterpane, down from his shoulder to a diagonal across his chest, raised himself to one elbow, leaned toward the night-table, snapped on the lamp first, and then the Dictaphone. He picked up the mouthpiece, made a final adjustment to a dial on the set, switched off the lamp, and lying flat on his back, in absolute darkness, began to speak:

“A letter, Miss Smart, to:

Editor

Tiny Car.

17 rue Danton

Berne, Switzerland

Dear Sir:

In your issue of 17 January you feature the article, by Jock Phillips, “Should Miniature Cars Run?”

First, let me say that I have

read

this article, that is to say, I have read . . . strike out the last seven words, Miss Smart. Period. Without referring directly to this article, however, let us consider the veritable host . . . the veritable

host

. . . underscore “host,” Miss Smart . . . veritable

host

. . . do not repeat it, however . . . the veritable

host

of implications posed here that might best be treated categorically, that is to say, in the strict sense of . . .

category.

Underscore. Period. Now, by way of preface, let us take . . . let us take . . . but do not repeat it . . . let us

take

. . .”

A Biography of Terry Southern

Terry Southern (1924–1995) was an American satirist, author, journalist, screenwriter, and educator and is considered one of the great literary minds of the second half of the twentieth century. His bestselling novels—

Candy

(1958), a spoof on pornography based on Voltaire’s

Candide

, and

The Magic Christian

(1959), a satire of the grossly rich also made into a movie starring Peter Sellers and Ringo Starr—established Southern as a literary and pop culture icon. Literary achievement evolved into a successful film career, with the Academy Award–nominated screenplays for

Dr. Strangelove, Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

(1964), which he wrote with Stanley Kubrick and Peter George, and

Easy Rider

(1969), which he wrote with Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper.

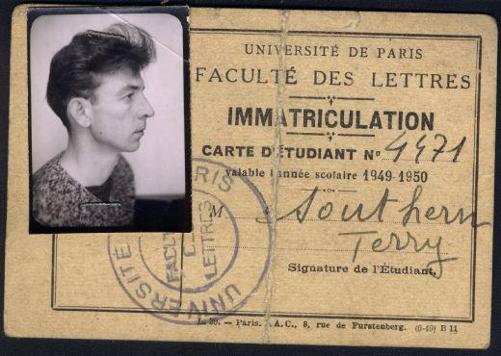

Born in Alvarado, Texas, Southern was educated at Southern Methodist University, the University of Chicago, and Northwestern, where he earned his bachelor’s degree. He served in the Army during World War II, and was part of the expatriate American café society of 1950s Paris, where he attended the Sorbonne on the GI Bill. In Paris, he befriended writers James Baldwin, James Jones, Mordecai Richler, and Christopher Logue, among others, and met the prominent French intellectuals Jean Cocteau, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Albert Camus. His short story “The Accident” was published in the inaugural issue of the

Paris Review

in 1953, and he became closely identified with the magazine’s founders, Harold L. Humes, Peter Matthiessen and George Plimpton, who became his lifelong friends. It was in Paris that Southern wrote his first novel,

Flash and Filigree

(1958), a satire of 1950s Los Angeles.

When he returned to the States, Southern moved to Greenwich Village, where he took an apartment with Aram Avakian (whom he’d met in Paris) and quickly became a major part of the artistic, literary, and music scene

populated by Larry Rivers, David Amram, Bruce Conner, Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, and Jack Kerouac, among others

. After marrying Carol Kauffman in 1956, he settled in Geneva until 1959. There he wrote

Candy

with friend and poet Mason Hoffenberg, and

The Magic Christian

. Carol and Terry’s son, Nile, was born in 1960 after the couple moved to Connecticut, near the novelist William Styron, another lifelong friend.

Three years later, Southern was invited by Stanley Kubrick to work on his new film starring Peter Sellers, which became,

Dr. Strangelove

.

Candy

, initially banned in France and England, pushed all of America’s post-war puritanical buttons and became a bestseller. Southern’s short pieces have appeared in the

Paris Review

,

Esquire

, the

Realist

,

Harper’s Bazaar

,

Glamour

,

Argosy

,

Playboy

, and the

Nation

, among others. His journalism for

Esquire

, particularly his 1962 piece “Twirling at Ole Miss,” was credited by Tom Wolfe for beginning the New Journalism style. In 1964 Southern was one of the most famous writers in the United States, with a successful career in journalism, his novel

Candy

at number one on the

New York Times

bestseller list, and

Dr. Strangelove

a hit at the box office.

After his success with

Strangelove

, Southern worked on a series of films, including the hugely successful

Easy Rider

. Other film credits include

The Loved One

,

The Cincinnati Kid

,

Barbarella

, and

The End of the Road

. He achieved pop-culture immortality when he was featured on the famous album cover of the Beatles’

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band

. However, despite working with some of the biggest names in film, music, and television, and a period in which he was making quite a lot of money (1964–1969), by 1970, Southern was plagued by financial troubles.

He published two more books:

Red-Dirt Marijuana and Other Tastes

(1967), a collection of stories and other short pieces, and

Blue Movie

(1970), a bawdy satire of Hollywood. In the 1980s, Southern wrote for

Saturday Night Live,

and his final novel,

Texas Summer

, was published in 1992. In his final years, Southern lectured on screenwriting at New York University and Columbia University. He collapsed on his way to class at Columbia on October 25, 1995, and died four days later.

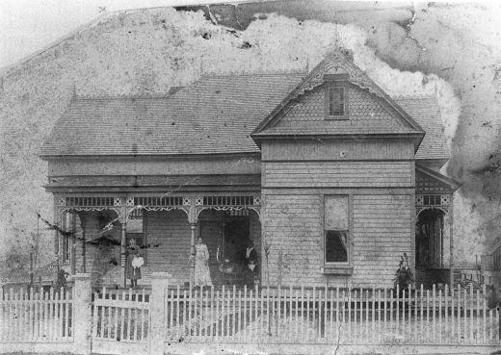

The Southern home in Alvarado, Texas, seen here in the 1880s.

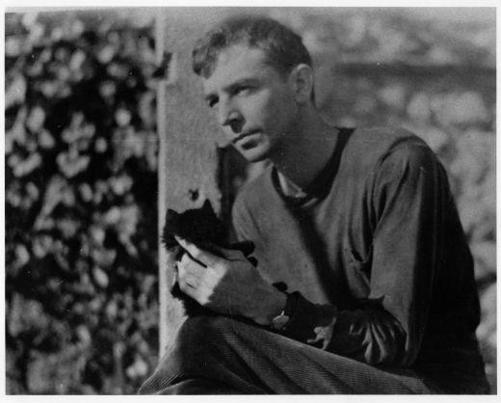

A young Southern with a dog in Alvarado, his hometown, around 1929.

Terry Southern Sr. with his son in Dallas, around 1930.

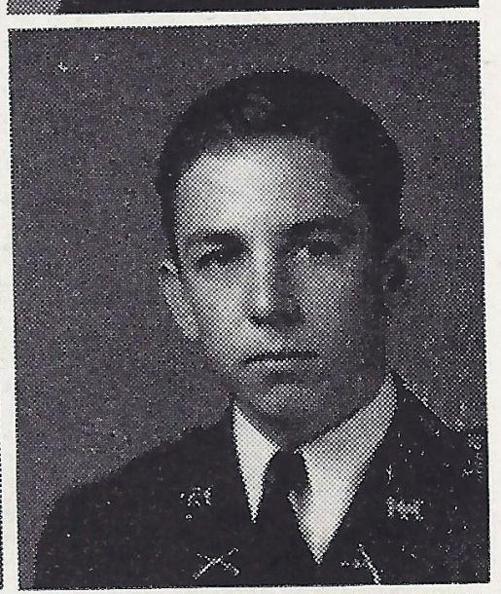

Southern’s yearbook photo from his senior year at Sunset High in 1941.

Southern before World War II. He was able to use the GI Bill to spend four years studying in Paris.